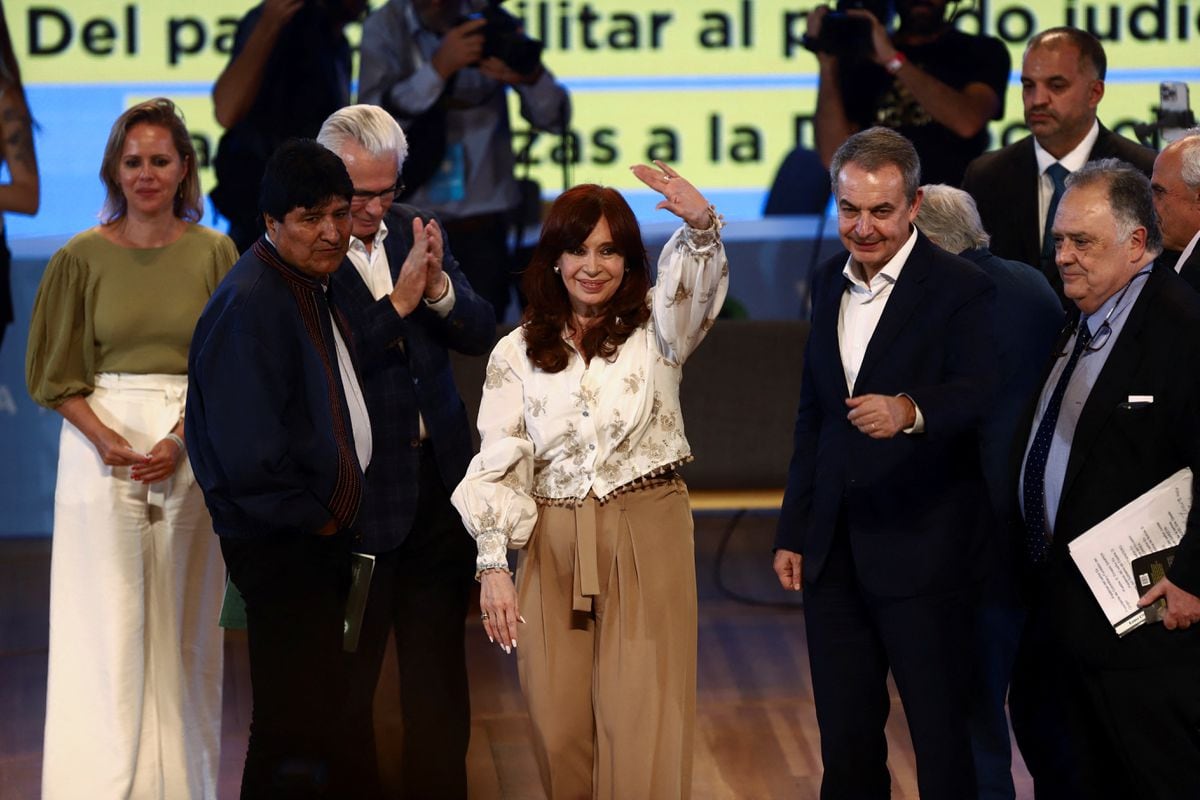

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner with José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, Evo Morales and Baltasar Garzón during a meeting of the Puebla Group in Argentina.MATIAS BAGLIETTO (REUTERS)

Latin America's progressive presidents, or those who boast of being so, frequently complain about some judicial decisions. In a particularly convulsive passage of his ten months in power, the Colombian Gustavo Petro, who had already warned of a possible conspiracy by the military to overthrow him, denounced this week a "soft coup" that threatens to decimate in Congress the Historic Pact, the leftist coalition that brought him to power, while the major legislative reforms proposed remain stuck. Almost at the same time, the Mexican Andrés Manuel López Obrador described as a "technical coup d'état" the rulings that seek to stop the flagship infrastructure works of his Administration.

The ambiguity of Petro's message – which he later explained referred to decisions of the Attorney General's Office and not of the courts – provoked criticism and confused locals and strangers, but illustrates the suspicions that have made a career. The idea of politicized justice has taken on regional dimensions. In the midst of the winds of change that a new layer of leftists has brought in Latin America, in several countries there is talk of legal persecution that targets the governments of the new pink wave. The meeting of the Puebla Group that brought together at the end of last year more than a hundred Ibero-American progressive leaders in Santa Marta, in the Colombian Caribbean, already discussed in its agenda the concept that in the Anglo-Saxon world is known as lawfare.

In that conclave, former Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff, herself dismissed by the Congress of her country in 2016, denounced "the use of legal instruments to destroy presidents", while former Colombian President Ernesto Samper criticized the "politicization of justice" that has been "vicious" with leaders such as current President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, prevented from competing in the 2018 elections because he was imprisoned – his processes were later annulled by justice. In very dissimilar cases, the leaders of the Puebla Group, who have been working on the issue, denounce the "legal wars" that have affected leaders such as Lula, Dilma, the Ecuadorian Rafael Correa or the Bolivian Evo Morales. They also sheltered Argentina's Cristina Kirchner in March, and the group has even created a specialized team of jurists to work on the different cases that includes the Spanish Baltasar Garzón and the Argentine Eugenio Raúl Zaffaroni.

Petro's case when he was mayor of Bogotá is considered an emblematic case of lawfare. The then prosecutor in charge of disciplinary sanctions against officials, Alejandro Ordóñez, an ultraconservative Lefebvrist of incendiary rhetoric, famous for his Catholic vision of the State, dismissed him and disqualified him for 15 years for failures in the implementation of a new model of sanitation in the Colombian capital. Petro obtained precautionary measures in his favorin the inter-American justice system, and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights sided with him in 2020, when it declared that the Colombian State had violated his political rights and that the powers of the Attorney General's Office to dismiss officials elected by popular vote should be eliminated.

"Legal wars are an instrument of political use of justice," says Samper, one of the main articulators of the Puebla Group along with Chilean Marco Enríquez-Ominami and Brazilian Aloizio Mercadante, whom Lula entrusted to direct the Brazilian Development Bank. "It is a form of attack that the right has found especially to question, hinder, hinder or even break the possibility that there are progressive characters who can advance in politics," he points out in dialogue with this newspaper. Legal wars aim to cause reputational, political and legal damage. "All lawfare munitions have to do with the affectation of due process," be it the presumption of innocence, the right to defense or the second instance. To the legal wars, Samper adds, other strategies can be added such as sowing distrust around the economy or fostering the feeling of institutional instability with the aim of eliminating the bases of governability. A review of the panorama of some countries in the region.

From the 'impeachment' to the Bolsonarist assault

In Brazil, the hypothesis of a coup, which flew over the four years of the Government of Jair Bolsonaro, became a reality on January 8 in Brasilia. On that day, a week after the inauguration of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, thousands of radical Bolsonaristas forcibly entered the National Congress, the Planalto Palace (the seat of government) and the Supreme Court. The mobilization of the extreme right, which had been camped for weeks asking for an intervention of the Armed Forces, remained in coup attempt. As of today, 1,044 people have been charged, and Bolsonaro is being investigated for allegedly instigating his supporters.

In addition to the coup attempt in the capital, in Brazil much of the left considers that the impeachment that former President Rousseff suffered in 2016 was a parliamentary coup. President Lula also used the lawfare thesis to explain his imprisonment, which prevented him from participating in the 2018 elections. The disclosure of the maneuvers of the then judge Sérgio Moro and the prosecutors to convict him and the archiving of several pending cases contributed to strengthen his story that he was the victim of a legal persecution that sought to end his political career.

"They want me imprisoned or dead"

In Argentina, the thesis on judicial persecution determines the political confrontation from the beginning of the investigation of the corruption case for which Vice President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner was sentenced to six years in prison and life disqualification. Although the ruling is not yet final, the number two of the Government has tried to install the idea of the ban. This week she made it clear by affirming, once again, that her political adversaries, among whom the leader includes the judicial system, seek to remove her from the political scene. "They want me imprisoned or dead," she wrote in a long letter posted on her social networks. It referred to two events.

In the first place, the assassination attempt that he suffered on September 1, the most serious event that has convulsed Argentina in its recent history. The Prosecutor's Office ruled out that there was a political motive behind the attack and decided to end the investigation into the attack by focusing on the three material authors. Secondly, Cristina Kirchner also alluded to her procedural situation. A court convicted her in December of defrauding the state and acquitted her of the crime of illicit association. The vice president rejected the ruling at the time with some harsh words: "This conviction is not a conviction by the laws of the Constitution or the Penal Code. This is a parallel state and mafia, judicial mafia." And this is the climate that permeates the public conversation and the dispute between parties with less than five months to go before the presidential elections.

"Technical coup d'état"

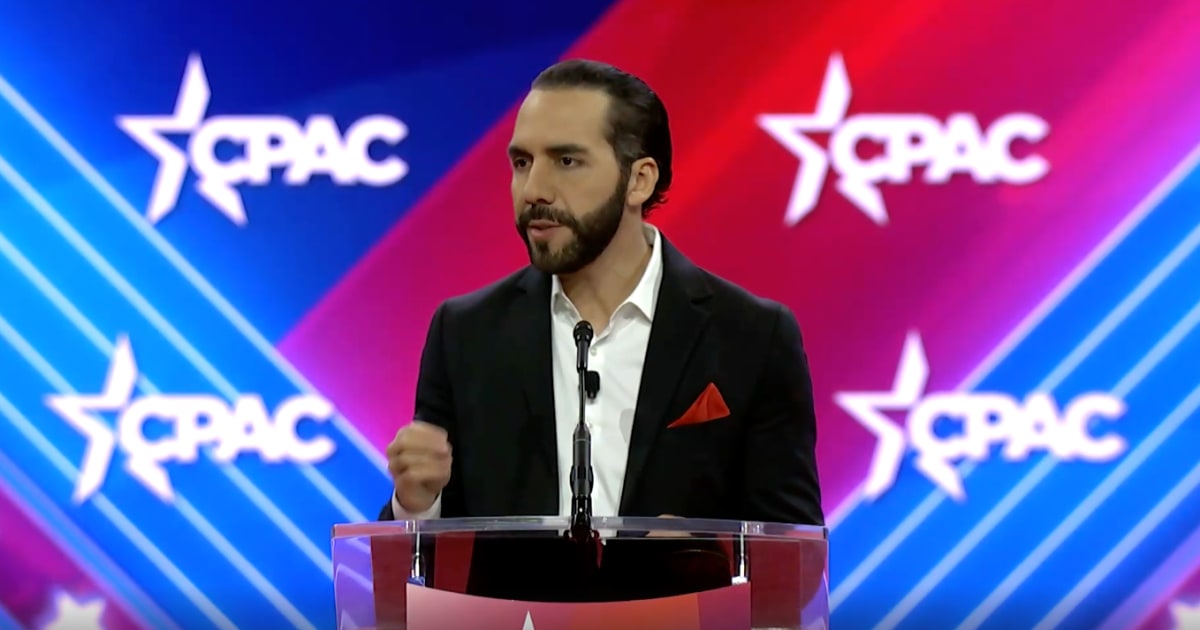

The president of Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, has maintained for years a pulse with a sector of the judicial apparatus that he considers linked to the country's political past. This week, however, the president went further in his remarks and accused the judges of pursuing a "technical coup d'etat" against his government. He was referring to the resolution of a federal court that ordered the definitive suspension of deforestation in four sections of the Mayan Train, one of the most important works of the Administration and, like no other, emblem of its political project, the so-called Fourth Transformation.

López Obrador assured in any case that he will not abide by the judicial ruling and, therefore, the works will continue. "They will continue to want to stop the works, but they will not be able to because according to the Constitution and the laws we have the right to do works for the benefit of the people," he said.

With information from Joan Royo Gual.

Subscribe here to the newsletter of EL PAÍS about Colombia and receive all the informative keys of the current situation of the country.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/FVXWW4XDH5BWDFX47AT65FDXDM.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/W33JSXVPKRF7FMDYEETPSPNNKY.jpg)