In 2015, scientists reported an astonishing discovery deep in a South African cave:

More than 1500 fossils of an ancient hominid species that had never been seen.

The creatures, belonging to Homo naledi, were short, with long arms, curved fingers and a brain one-third the size of a modern human.

They lived at the time when the first humans were moving through Africa.

Engravings on a wall of the Rising Star cave in South Africa. Researchers claim the marks were created by a small-brained relative of humans, Homo naledi, more than 240,000 years ago. Photo Berger et al. (2023b)

Now, after years of analyzing the surfaces and sediments of the elaborate underground cave, the same team of scientists makes another surprising announcement:

Homo naledi (despite having a tiny brain) buried their dead in graves.

They lit fires to light their way through the cave and marked the graves with engravings on the walls.

Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, in Rising Star Cave. Photo Robert Clark/National Geographic

Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and director of the project, said the discovery of a small-brained hominid doing such human things had great significance.

Berger suggests that big brains are not essential for sophisticated thinking, such as creating symbols, cooperating on dangerous expeditions, or even recognizing death.

"This is that 'Star Trek' moment," he said.

"You go out, you meet a species, it's not human, but it's just as complex as humans.

What do you do?

That's where we are, right now."

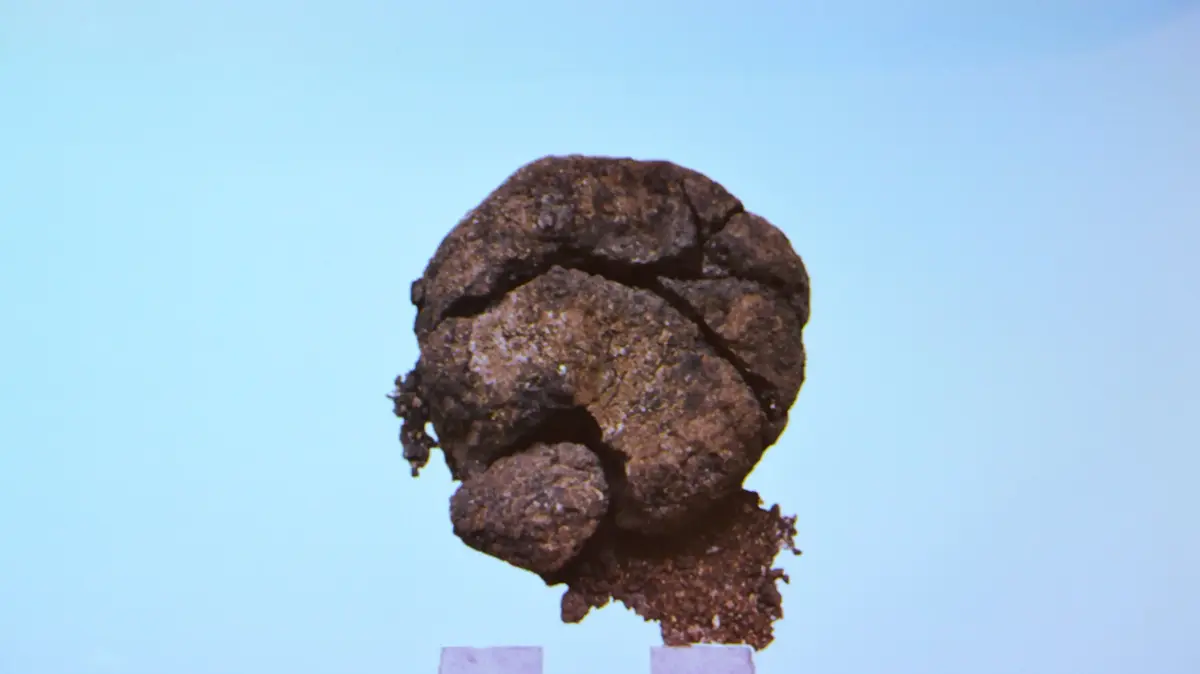

Fossils of H. naledi at the Institute of Evolutionary Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg in 2014. Photo Robert Clark/National Geographic

However, several experts on ancient engravings and burials said the evidence did not yet support these extraordinary conclusions about Homo naledi.

They said the evidence found so far in the caves could have a number of other explanations.

For example, it is likely that the skeletons were abandoned on the cave floor, and perhaps the charcoal and engravings found in the cave had been left by modern humans who entered long after Homo naledi became extinct.

"It seems that the story is more important than the facts," said Maxime Aubert, an archaeologist at Australia's Griffith University.

Berger was scheduled to present his findings at a scientific meeting on Monday, and the journal eLife will publish three papers detailing the evidence.

According to a spokesperson for the journal, the studies are currently in the peer review phase and will be published when they have concluded.

In 2013, two South African cavers exploring Rising Star Cave discovered the remains of Homo naledi.

Expedition

Berger organized an expedition to the complex system of chambers and tunnels, which stretches for miles underground.

"When you're in there, it's like you're on another planet," said Tebogo Makhubela, a geologist at the University of Johannesburg who joined the team in 2014.

The researchers found a large number of bones, but to reach them it was necessary to practice risky caving.

Some passageways were so narrow that only the smallest members of the team could pass.

In total, researchers have found bones from at least 27 individuals.

Berger and his colleagues found it unlikely that they had simply been swept away by the current deep into the cave.

In their 2015 report, the researchers suggested that Homo naledi took the bodies there on purpose, but left them on the cave floor instead of burying them, an act archaeologists call "burial deposit."

It was a challenging statement, given how primitive Homo naledi looked.

Berger and his colleagues argued that the species belonged to a lineage that diverged from our ancestors more than 2 million years ago.

While our lineage grew and developed a large brain, theirs did not.

At first, scientists thought the fossils were scattered evenly across the chamber floor, but upon excavating more sediment in 2018, they observed that two fairly complete skeletons rested within oval depressions.

And it didn't look like the skeletons had formed the depressions by sinking into the sediment.

For example, there was an orange layer of mud surrounding the ovals, but it was not inside.

Along the edges, the excavation had a neat appearance.

This finding, as well as other lines of evidence, have led Makhubela and his colleagues to conclude now that the remains had been buried.

"Apparently, they all detail the same story," he said.

Until now, it was only known that humans buried their dead and the oldest known human grave dates back 78,000 years.

Homo naledi lived much earlier.

Makhubela noted that his fossils were at least 240,000 years old and could be up to 500,000 years old.

The scientists also found chunks of charcoal, burned bones of turtles and rabbits, and soot on the cave walls near the fossils.

Therefore, they suggested that Homo naledi used burning coals to light themselves inside the caves and carried wood or other fuel to make fire.

They may have cooked the animals for food, or they may have done so as a ritual.

When these new discoveries came to light, Berger decided he had to take a look for himself at one of the chambers, known as Dinaledi, which contained a supposed tomb.

He had to lose 25 kilos to be able to cross the passageway.

By July, I was ready for the trip.

Evidence

Berger went in alone and examined the fossils.

On leaving, he passed by a pillar.

On one of its sides, he observed a set of grooves similar to numeral symbols engraved on the hard surface.

Going out was harder than getting in.

"I was about to die," Berger explained, but he managed to escape with a torn rotator cuff.

Two members of the team, Agustín Fuentes of Princeton University and John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin, were waiting for him in the next chamber.

Berger showed them the photographs he had taken of the grooves.

The two scientists immediately took out their phones and showed the same picture:

an engraving made by Neanderthals in a cave in Gibraltar.

It was strikingly similar to what Berger had just seen.

Based on the growing number of fossils scientists are finding in Rising Star, Fuentes noted, it seems as if Homo naledi may have visited the cave for perhaps hundreds of generations, moving together into the dark depths to bury their dead and mark the spot with art.

This kind of cultural practice, Fuentes argued, would have demanded some kind of language.

"You can't do that without some kind of complex communication," he said.

"I'm very optimistic about the existence of burials, but there's no consensus on it yet, it's not clear," said Michael Petraglia, director of the Australian Centre for Human Evolution Research.

Petraglia wanted to see more detailed analyses of the sediments and other types of evidence before judging whether the ovals were burials.

"The problem is that they got ahead of the science," he said.

Paul Pettitt, an archaeologist at Durham University, UK, said it was possible that Homo naledi did not bring the corpses, either to deposit them or to bury them. It is likely that the bodies had been swept away by the current.

"I'm not convinced the team proved that this was a deliberate burial," he said.

As for the engravings and bonfires, experts said it was not clear that Homo naledi was responsible for them.

It was possible that they were the work of modern humans who arrived in the cave thousands of years later.

"All this is, to say the least, unconvincing," said João Zilhão, an archaeologist at the University of Barcelona.

One way to test these possibilities would be to collect samples of engravings, charcoal and soot to calculate their age.

If a hominid like Homo naledi could make engravings and dig graves, it would mean brain size wasn't essential for complex thinking, said Dietrich Stout, a neuroscientist at Emory University who was not involved in the studies.

"I think the interesting question going forward is what exactly you need a big brain for," Stout said.

c.2023 The New York Times Company

See also

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/PH7553GPABDL5BZOBP775AC5E4.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/DXPUIGHRZZEKNMVHLDNKFJFAMY.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/2P2FATFESJDD5BB6NR7VLSJ7QY.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/RGH6L3ASCJDP5GAMDDL3CKX7OY.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/KMEYMJKESBAZBE4MRBAM4TGHIQ.jpg)