By Lisa Cavazuti, Cynthia McFadden and Rich Schapiro -

NBC News

On the night of March 17, 2020, a former Mexican police officer working for the Sinaloa cartel left his hotel room in Tijuana and crossed the U.S. border into Southern California on foot at 10:09 p.m.

Ricardo Ramos Medina

's first stop

was the San Diego International Airport, where he picked up a rental car.

He drove to a nearby location and met a woman who handed him a grocery bag full of methamphetamine.

He then set out on a much longer trip: 16 hours to

Montana

.

Medina had made that same trip several times, but this time it didn't go as planned.

Before arriving in Butte, he was detained by state and federal agents.

Inside his white Jeep Compass they found half a kilo of pure methamphetamine, enough, according to authorities, to supply the entire city of Townsend, Montana (2,150 inhabitants), for several days.

The arrest, described in court documents and in interviews with investigators in the case, helped dismantle

a drug trafficking network

that, according to federal prosecutors, brought at least 1,000 kilos of methamphetamines and 700,000 fentanyl pills into Montana from Mexico, throughout of three years.

“Why Montana?” asked Chad Anderberg, an agent with the state Division of Criminal Investigation who was one of the lead investigators on the case.

"For the money.

He could make a lot more profit from the drugs he sold here than in any other state.”

[Latino parents who sue Snapchat after the death of their children from fentanyl speak out: "I used that social network a lot"]

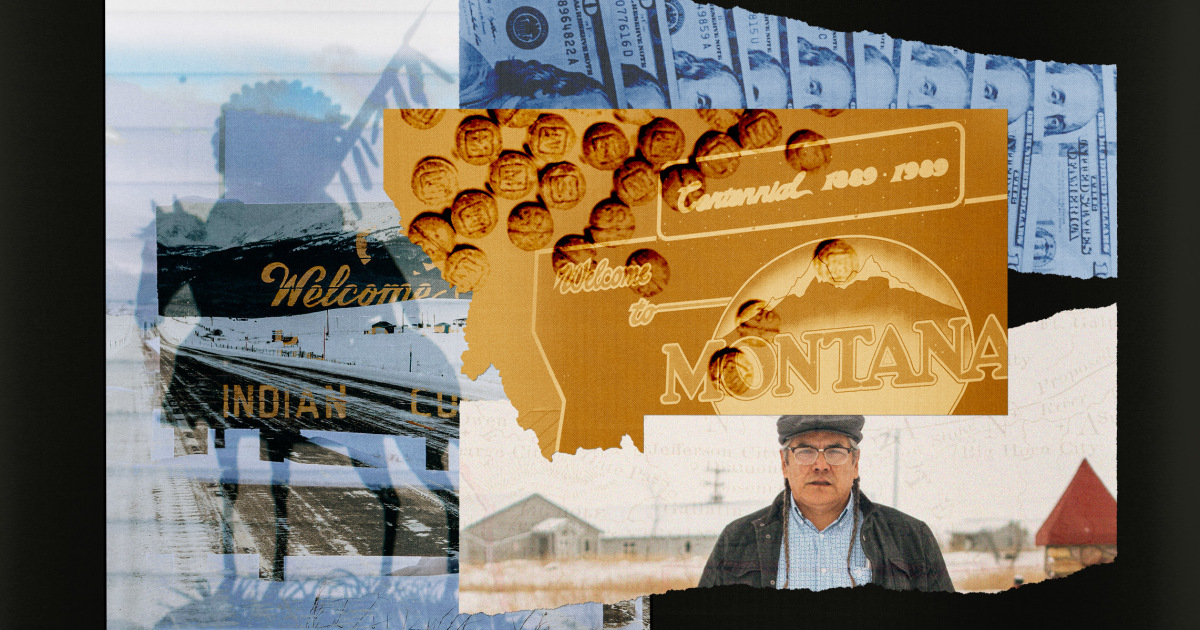

Illegal drugs have long flowed from Mexico to the most remote areas of the U.S. But with fentanyl production increasing, cartels have moved more aggressively into

Montana, where the pills can sell for 20 times as much. the price

they get in urban centers closest to the border, according to state and federal officials.

Some areas of the state are inundated with drugs, especially Indian reservations where, according to tribal leaders, crime and overdoses are increasing.

On some reservations, cartel members have formed relationships with indigenous women to establish themselves in communities and sell drugs, according to law enforcement officials and tribal leaders.

More often, traffickers lure Native Americans to become dealers by gifting them an initial supply of drugs and turning them into addicts indebted to the cartels.

“Right now it's

like fentanyl is raining down

on our reservation,” said Marvin Weatherwax Jr., a member of the Blackfoot Tribe's Business Council and representative of District 15 in the Montana House of Representatives.

Fighting drug trafficking is difficult in a state as large as Montana, where law enforcement has difficulty policing open spaces and reservations rely on underfunded and understaffed tribal police forces.

On at least one reservation, tribal members formed a vigilante group in a desperate attempt to fight drug crime.

However, Montana officials have made progress in the past two years.

The arrest of the former Mexican police officer was part of a massive raid that nabbed 21 other members of a drug trafficking gang linked to the Sinaloa cartel, one of the most powerful criminal organizations in the world.

And since last April, 26 suspects have been charged in a second federal case involving associates of the Mexican cartel and members of two Native American tribes.

[How this mother's fatal overdose led to the dismantling of a national fentanyl trafficking ring]

“People are shocked,” said Jesse Laslovich, the U.S. attorney for Montana, who has overseen the investigations.

“It is a state as far north as the United States and yet there is a cartel present.”

Montana, an unexpected place for drug trafficking

Stacy Zinn spent her first four years at the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in El Paso, Texas, where she investigated Mexican cartels.

She later worked in Afghanistan and Peru pursuing narcoterrorists and cocaine traffickers.

In 2014, the DEA transferred her to Montana and later placed her in charge of its offices in Billings, Great Falls and Missoula.

“When they promoted me and said, 'You're going to Montana,' I said, 'Montana?

Are there drugs in Montana?'” recalls Zinn, who retired from the DEA in October after 23 years.

This state is sometimes referred to as “the last great place” in the United States.

Its 1.2 million residents are spread across 150,000 square miles of mostly mountains, rivers and rugged terrain.

Locally manufactured methamphetamines were long Montana's biggest scourge.

But in the mid-2000s, the once-rich methamphetamine production centers of the Midwest and northern states began to disappear, due to new restrictions prohibiting access to the drug's chemical precursors.

According to law enforcement,

Mexican cartels saw an opportunity

and began to capitalize, flooding the United States with a super-potent form of methamphetamines and targeting indigenous communities in particular.

Zinn was surprised by the extent of the meth problem when he arrived in Montana 10 years ago.

But these drugs were soon eclipsed by fentanyl, which is even cheaper to produce and much deadlier.

[Joe Biden and Xi Jinping agree to curb fentanyl production: we summarize the highlights of their meeting]

A counterfeit fentanyl pill that can be made for less than 25 cents in Mexico sells for between $3 and $5 in cities like Seattle and Denver, where drug markets are more established, but for up to $100 in remote areas of Montana. .

It was one of the few states that had not attracted the attention of Mexican cartels, Zinn said, but that soon changed.

“The benefits are from another world,” he said.

Zinn was more than 1,300 miles from the southern border and had to return to investigate the Mexican cartels: the Sinaloa cartel and the Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG).

“I got emotional,” Zinn said.

“This is the territory I know and understand.”

At first I only heard “rumors” about the presence of a cartel.

However, over the years, the cartel partners have become bolder and more willing to expand their operations.

“The cartel often sends advance teams or individuals to find out who is distributing small quantities in a specific reserve, who they can get their claws into,” Zinn said.

“And when it does, it takes over.

We see it again and again.”

Women are usually the main targets.

Cartel partners have pursued single women on reservations, according to law enforcement and tribal officials, and then used their homes as a base of operations.

[Charges are filed against the husband of the owner of the Bronx daycare where a baby died from fentanyl]

“They know who to pick,” said Stephanie Iron Shooter, director of Native American health for the Montana Department of Health and Human Services.

“Like any other situation where there is a predator, that's how things work.”

The drug crisis has been experienced most intensely on Montana Indian reservations.

Between 2017 and 2020, the opioid overdose death rate in Montana nearly tripled (from 2.7 deaths per 100,000 residents to 7.3).

In the decade before 2020, the rate of overdose deaths among Native Americans was more than twice that of white Montana residents, according to the state Department of Health and Human Services.

In many ways, Indian reservations are ideal places for drug trafficking operations to be established.

The communities suffer from high rates of drug addiction and there are few law enforcement agencies.

According to the tribal council, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe has two tribal police officers per shift, funded by the federal government, to patrol more than 440,000 acres of land where about 6,000 residents live.

The adjacent Crow Reservation, the state's largest, has four to six police officers per shift patrolling a swath of land the size of Rhode Island, according to Quincy Dabney, mayor of Lodge Grass, a town on the reservation.

“When we don't have agents on the ground and people aren't held accountable, it becomes the Wild West,” says Laslovich, the federal prosecutor.

“I think you see that in Indian Country, here in Montana, more than we should.”

To further complicate matters, reservations are sovereign nations where local security forces cannot act without an agreement with the tribe.

Even where agreements exist, state and local authorities are often prohibited from detaining tribal members.

And tribal police are largely prohibited from detaining people from outside the reservation.

[Nation's first drug decriminalization law, in Oregon, faces rejection amid fentanyl crisis]

All of this creates a jurisdictional labyrinth that makes fighting crime difficult at a time when drugs are ravaging indigenous communities, current and former law enforcement officials said.

“We're fighting this problem on one leg, and half the time we're handcuffed,” Zinn says.

The fall of a police officer turned drug trafficker

The case involving the former Mexican police officer turned drug trafficker was set in motion a couple of years earlier, when the Butte-Silver Bow Sheriff's Office received an intriguing tip.

In September 2018, a worker at a local FedEx store called to report that several people had been entering the store and stuffing wads of cash into packages headed to the border city of San Ysidro, California (Fed-Ex prohibits the shipment of cash).

A couple of months later, one of the people sending the money admitted to investigators that it was money from drug trafficking linked to an organization in Mexico.

Over the next few months, DEA task force investigators secured a cooperating witness.

The witness introduced an undercover agent to the man who supplied the drugs from his base in Sinaloa (Mexico): Humberto Villarreal.

“You don't get these types of cases where it's trafficked directly from Mexico,” said Sergeant Kevin Maloughney, an 18-year veteran of the Butte-Silver Bow Sheriff's Office.

[Deaths from drug overdoses register a historical record and the blame is not only on the coronavirus pandemic]

The agents soon ordered methamphetamine and fentanyl-laced pills directly from Villarreal.

According to authorities, drugs often came to Montana from stash houses in Southern California.

Investigators zeroed in on Medina, a former police officer and Villarreal's cousin, after he was arrested on the Fort Peck reservation in the state's northeast corner for running a stop sign in March 2019.

The sheriff's deputy let him go with a warning.

But a report about the unusual encounter with a Mexican national in such a remote area of Montana later reached agents investigating drug trafficking.

They discovered that Medina was a key piece of the drug trafficking network.

She had valid U.S. visas, making it easier for her to cross into the United States through the port of San Ysidro, California, on trips to pick up cash and deliver drugs.

“Since he had no criminal record, there was no reason for him to be investigated further,” said Anderberg, the Montana investigator.

After his arrest, Medina told investigators that he had traveled to Fort Peck with the intention of expanding the cartel's drug trafficking operations to the reservation, according to Anderberg.

The multi-agency investigation resulted in the seizure of 65 pounds of methamphetamine, more than 2,000 counterfeit OxyContin pills laced with fentanyl, and 3 pounds of heroin.

Agents also seized more than $32,000 in cash and 19 firearms, according to the Montana District Attorney's Office.

Villarreal was sentenced to 17 years in prison after pleading guilty to charges of possession with intent to distribute methamphetamine and conspiracy to commit money laundering.

Medina pleaded guilty to possession with intent to distribute controlled substances.

He was sentenced to eight years in prison.

Twenty other people were also convicted for their participation in the drug trafficking network.

[First it was fentanyl. Now this state counts the victims of another deadly drug]

A second federal drug case in Montana has led to charges against more than two dozen people and includes allegations that members of the Mexican cartel used Native Americans in the operation.

The investigation, still ongoing, focuses on the Crow Indian Reservation, where authorities say cartel partners took over at least two properties and used them to distribute methamphetamine to residents of the reservation, as well as the nearby reservation. Northern Cheyenne Indian and the city of Billings.

Lawyers for two of the defendants, Ranita R. Redfield and Zachary D. Bacon, described in court documents how they were used by the cartel.

Redfield's attorney wrote that she returned to the Crow reservation after going through a period of family turmoil and heartbreak, and that's when she fell into the clutches of the cartel.

“Choosing to distance herself from people who knew her from the past and having no place to live, she often stayed with the cartel,” wrote the attorney, Jessica Polan Wright.

“Caught in the vicious cycle of addiction and under the control of the cartel, Ranita became a pawn in their operations.”

Redfield, 47, who pleaded guilty to trafficking methamphetamine and was sentenced in December to five years in prison.

Bacon, 35, became involved in the operation after meeting the daughter of one of the Native American drug dealers, his attorney wrote in court documents.

In September he pleaded guilty to selling methamphetamine and was sentenced to five years' probation.

“The cartel's business model is to first locate local distributors and ingratiate themselves with them.

Then, when the bills started coming in, they brought in other, less friendly individuals,” wrote the attorney, Matthew Claus.

“The cartel removed tens of thousands of dollars in cash, weapons and vehicles from the Crow Reservation.

The money and weapons left the state and the country and then the cartel left.

In their wake,

they left addicted, drugged and impoverished tribal members

facing prosecution and long prison sentences, like Zach Bacon,” Claus added.

[The opioid crisis is not just a white problem: deaths among Hispanics have skyrocketed]

The alleged ringleader, a member of the Jalisco Nueva Generación cartel and known by the name Carlos, fled the state, according to police sources.

More overdose deaths and fewer resources to confront the cartels

The Blackfeet Reservation in northern Montana was rocked by tragedy in March 2022. In a single week, 17 people suffered fentanyl overdoses, four of them fatal.

The community is home to the only inpatient treatment center on a Montana Indian Reservation.

But Crystal Creek Lodge Treatment Center, with 16 beds, has long focused on people struggling with alcohol abuse.

“We are short on resources to deal with a crisis that not even our facilities are equipped to handle,” said Durand Tyland Bear Medicine, director of the center.

In southeastern Montana, the Northern Cheyenne reservation also suffers from a drug epidemic, but fueled by methamphetamine.

Some of the drugs entering the reservation come from the network of cartels that operate on the neighboring Crow reservation, prosecutors say in court documents.

Serena Weatherwelt, chairwoman of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe, said violent crime and robberies spiked during the pandemic, and calls to police often went unanswered.

The situation became so dire that some members of the tribe formed their own vigilante group, the People's Camp.

“They had cars.

They had spotlights.

They had a telephone,” she explains.

“People called that number instead of calling the police.”

[New York police officer arrested for trafficking drugs while on duty]

In 2022, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe filed a federal lawsuit against the Department of the Interior and its Bureau of Indian Affairs, alleging that the federal government had breached its obligation to keep reservation residents safe by failing to provide law enforcement officers. suitable.

A spokesperson for the Bureau of Indian Affairs said the agency does not comment on ongoing litigation.

Weatherelt said the situation went from bad to worse in the months after his tribe filed the lawsuit.

Last December, a tribal police chief notified Wetherelt that a federally funded reorganization of the force meant the number of officers and other personnel had been reduced from 19 to 7, according to members of the Northern Cheyenne Tribal Council.

“We don't ask much of the government,” Weatherelt said.

“We call for basic law enforcement to help our people…”

His voice cracked with emotion and then he was silent briefly.

“I'm sorry, but this excites me,” she continued.

“It feels like we're going nowhere.”