This is the web version of Americanas, the EL PAÍS América newsletter in which it addresses news and ideas with a gender perspective.

If you want to subscribe, you can do so

at this link

.

They named her Damiana so that the little girl would have a Spanish name and her new caregivers could refer to her without having to refer to her mother tongue, and thus, neither to her origin, nor to her family nor to the town to which she belonged and which they wanted to exterminate. : the Aché.

In 1896, deep in the Paraguayan jungle, Damiana's family was murdered and she was kidnapped to be the servant of a "white" family, who years later locked her in a psychiatric hospital under the care of an anthropologist.

Her death, at age 14, was not the end of that path.

Her skull was sent to Germany and her skeleton was forgotten for decades in a museum in Argentina, until, in 2010, her people, still alive, received her first remains in a moving ceremony.

She was two or three years old when they stripped her of everything that made up her identity.

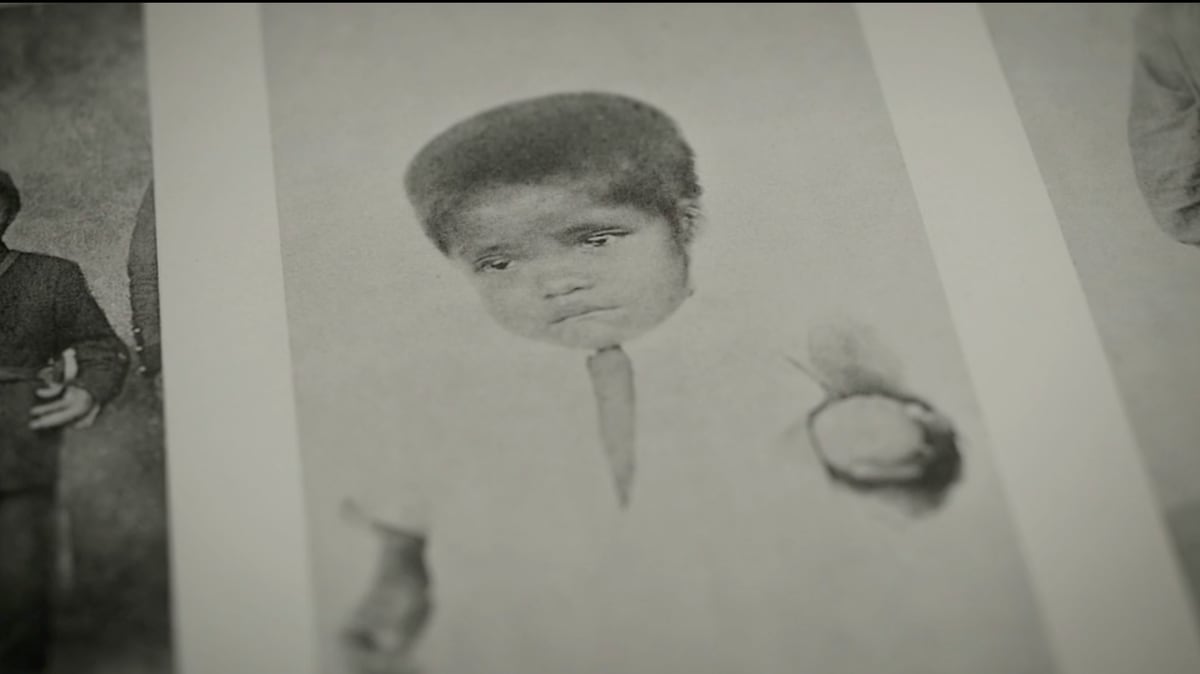

A photograph taken by Dutch anthropologist Herman Ten Kate, shortly after her capture, shows the face of that little girl with a look of horror, terror and sadness.

The story of their horror began in September 1896, when a group of one or several families of settlers entered the Paraguayan jungle to ambush a group of Aches - an ethnic group of hunters and gatherers who live in Paraguay and who lived with relative political autonomy until 1959, with the processes of forced sedentarization—who lived together around a campfire, were blamed for having killed one of their horses.

They murdered all of her and took her away.

She lived for some years in Paraguay, where she was baptized with the name that corresponded in the Catholic saints to the day on which her entire clan was destroyed: September 26, the day of San Damiano.

Two years later, Damiana was taken to San Vicente, about 50 kilometers south of Buenos Aires, Argentina, where she was the servant of a German family with the last name Korn.

She lived there during that first part of her life, until her sexual awakening and an illness that was slowly consuming her, ended up making the family fed up—they couldn't stand the 'inappropriate' behavior that they identified in the teenager—and they hospitalized her. at the Melchor Romero psychiatric hospital, in the city of La Plata.

The Argentine filmmaker Alejandro Fernández Mouján is perhaps, in addition to the anthropologists who carefully studied Damiana and the representatives of the Aché themselves, one of the people who has most researched and documented this fact.

In 2015, after five years of exhaustive work, Fernández Mouján premiered the documentary

Damiana Kryygi

, in which he participated in writing, directing and producing it.

“When I look at this photo, I wonder if it is possible to reconstruct its history, to respond to that gaze,” says the voice of the filmmaker who narrates the documentary.

To make this film, Fernández Mouján traveled to the Aché communities in Paraguay and also traveled on several occasions to Germany and Argentina to follow the trail of Damiana's story, which came to him thanks to the story of his wife, a professor of Anthropology. in Argentina.

“I read it, I think, in 2002 and I thought it was interesting, but I also thought that there weren't many elements to work on.

Plus he was finishing one movie and trying to start another.

It wasn't until more or less between 2007 and 2009, when her remains had already been found, that it seemed to me that there was the possibility of making a film,” he recalls.

The welcoming ceremony, one hundred years later

In the documentary, considered a very important anthropological work for the history of the Aché people, you can observe the step by step of an investigation into the brief life of a girl who died before being able to decide about her own existence.

In addition, Mouján shows part of the ceremony in 2012 through deeply moving images of old men and women, young people and children who cry in front of the two portraits of Damiana - one at three years old and the one taken two months before her death. , at 14 years-.

After the restitution of her remains, the Aché people baptized her as Kryygi (mountain armadillo).

When asked about the distance of the events and the latent sadness that those scenes from 2012 demonstrate, the director recalls: “Damiana represents all those who could not return, neither alive nor dead.

It is the first time that she returns a dead person, that their remains return.

So, she is a symbol of the return of all those who we could never see again, who never knew what happened again, and who did not return neither alive nor dead, nor in any way.

The Paraguayan academic Miguel H. López, in the article

Kryýgi, the Aché girl restored after 120 years,

from the magazine Debates Indígenas, precisely describes part of that ceremony: “Three women brought in the remains, while the men became agitated and broadcast their

jambu

(roars).

Inside, the

chĩnga

(lamentations and cries of complaint) and the plaintive

pre'e

(singing) filled with anguish one of the most emblematic moments experienced by the Aché: the reincorporation of their members stripped by the

beru

(white man) and the

apã proro

(white men with guns) more than a century ago.

Furthermore, the reunion of northerners and southerners diluted the ancestral difference between the

gatu

,

wa

(group to which the late Kryýgi mái belonged) and the

iroiãngi.”

Damiana Kryygi, young woman from the Aché ethnic group.

Appropriate, servant of an aristocratic family, scientific "object" of the Museum of La Plata.

1907 pic.twitter.com/CHyhqDKOZR

— Federico Kukso (@fedkukso) September 9, 2017

In 1907, Damiana Kryygi died of tuberculosis, just two months after the head of the anthropological section of the La Plata Museum, the German Roberto Lehmann-Nitsche, carried out studies on her and forced her to undress to take the last photograph.

She was 14 years old and her skeleton would be forgotten in a corner of the museum until 2010, when she returned to her community.

Two years later, in 2012, her skull would also be recovered, after remaining at the La Charité Hospital in Berlin, where it was exposed.

For director Mouján, the story of Damiana Kryygi is the story of many of the indigenous peoples in Latin America who were erased and annulled without anything happening.

“What we did was like the series of detectives who follow any clue that appears.

Any trace, image, text, similarity or where it could be, we followed it during, well, those five years it took us to make the film.

The investigation never ended, let's say, even after we found some records that could be hers, but we were not entirely sure because the name was changed,” he concludes.

The Aché genocide in the Stroessner dictatorship

In April 2014, a group of Aches presented a complaint in an Argentine court for genocide against their people, during the dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner.

The lawsuit was supported by Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón.

“We were a town of 6,000 people and now we are about 2,000.

It is a tragedy to which the Paraguayan State does not want to respond,” said Ceferino Kreigi, representative of the Aché National Federation.

During the years in which Stroessner imposed the military dictatorship (1954-1989), specifically in the sixties and seventies, the Aché suffered forced eviction from their ancestral lands, lack of medical care, and the sale of their children for domestic work—they were kidnapped, like Daniana Kryygi, into servitude to white families.

“90% of the Aché deaths between 1960 and 1970 were caused by non-indigenous people, according to the anthropologist Bartomeu Melià, who, paraphrasing the Swiss naturalist and doctor Johann Rudolf Rengger, expressed in 1832 that 'the history of Paraguay is the history of the destruction of the Guaraní nation', alluding that today the genocide of indigenous people and peasants is caused by extensive soybean cultivation and the alienation of their lands by agribusiness and foreigners," says Miguel H. López, in another of his articles published in 2014 .

Our recommendations of the week

Thank you very much for joining us and see you next Monday!

(If you have been sent this newsletter and want to subscribe to receive it in your email,

you can do so here

).

Subscribe to the EL PAÍS México newsletter

and the

WhatsApp channel

and receive all the key information on current events in this country.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I am already a subscriber

_