Cuban food does not exist.

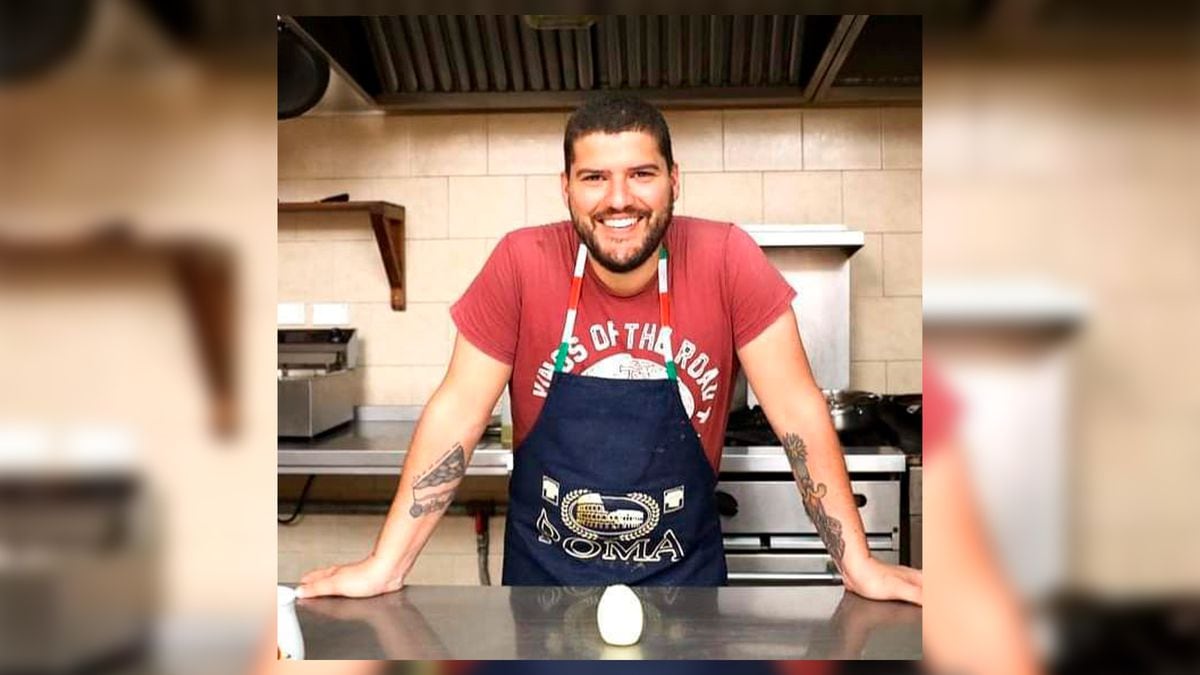

Raulito Basuk says it, who is not exactly a chef or a cook, but rather a “food shaman.”

Cuban food does not exist and, therefore, everything we believed until now, Raulito has demystified: from the flan recipes in the book by the famous chef Nitza Villapol, to the ajiaco that the historian Fernando Ortiz appropriated, through the casabe, for the much acclaimed old clothing that actually comes from the Canary Islands, or the congrí, which comes from Haiti, and which mutates to the gallo pinto in Costa Rica, to the Moors and Christians in the Iberian countries, or to the casabe in El Salvador.

Cuban food does not exist, in reality, because “it is not being cooked in the national pot.”

Right on E Street, between 23 and 25, in Havana's Vedado neighborhood, Raulito, 38, has his restaurant, or rather his palate, he rectifies, so that no one is confused.

In the nineties, in the midst of the crisis that in Cuba was called the Special Period, national television broadcast the Brazilian soap opera

Vale todo,

whose protagonist goes from selling sandwiches on the beach to opening his first restaurant called Paladar, a name that appealed to the flavor or to taste.

At the same time, in the midst of the economic debacle that the Government could not resolve, the first licenses were granted in the country for Cubans to open their own businesses, which began to flourish in the living rooms of their homes, allowing up to 12 chairs for 12 diners having dinner from the family cauldron.

Paladar is a name that has remained until today, which names many of the small neighborhood businesses that stand on the rooftops, doorways and garages of the Cuban family, and is used as a cool way by

more

prosperous places like Paladar San Cristóbal, where the Obamas ate during their visit to Havana.

“The palate is everyone's place,” says Raulito.

That's why Grados, the space that opened in 2017 in the living room of the house that her mother inherited, is more of a palate, like the one her mother made in the nineties to survive while selling ice cream cake, or the one her mother made. grandmother and her uncle.

Now that we speak, he has stopped by to greet a retired teacher to whom Raulito offers a drink of rum, a tartlet seller from whom he has bought a sweet for each of the twelve members of his team, a man to whom he has offered a plate of food, and has asked for a good slice of avocado.

“I wanted to create a Cuban cuisine restaurant, a paladar.

That's Grados, it's a palate."

After finishing his studies at the Vladimir Ilich Lenin Vocational School of Exact Sciences, Raulito studied Cybernetics.

He then went to Montevideo to take cooking classes at the Gato Dumas school, and became a Professional in Culinary Art and gastronomic management.

Before returning to Cuba and opening Grados, Raulito worked in several restaurants in Uruguay, Argentina and Spain.

In this country, he cooked in the Atrium, which appears on the succulent lists of the Michelin guide.

“When I did Grados, I had ideas, I had gone to several countries, I had worked in several places, but I still didn't know how to cook.

And I’m still learning to understand the jama thing,” she says.

Jama is a word that Raulito will continue to mention, and that is used in Cuba to name food.

For example, Raulito says that today he does not see “la jama” as he saw it before.

“Some time ago, he saw the jama as less transcendental than I see it now.

In the sense of what it means, what importance you give it, and above all, how much you find yourself thinking about food, not just as food, but the way people relate to each other through food.”

And why is the issue of food so transcendental now?

“What happens now is that I extend the thinking about food a little more,” she responds.

“I was thinking about the moment after you eat, after you chew, taste the food, generate a bodily expression.

You eat something and you always say if it is good, if it is bad.

People never, and have to say something, in any circumstance.

Food in children, for example, is one of the first exercises of will that human beings have.

The child cries and until he finally gets it, he doesn't stop.

And later, when he grows up, it is the first time that he can exercise will and freedom from the point of view of decision-making.

So, eating is an exercise of freedom.

“He is the first of all,” she says.

In Cuba, a country where food is scarce, and where people use the word “hunger,” what degrees of freedom does a person experience when it comes to food?

Raulito says it depends on the social class you belong to.

“I don't know if in Cuba we can talk about social classes, but not everyone has equal access to food.

Food is a problem that has to do with access, with production.

The jama theme has a life of its own.

I suffer from that, because in Grados I have to give the richest jama, it is super elitist.

Degrees are expensive, almost no one has access in Cuba, except foreigners, tourists,” he says in a video call interview with EL PAÍS.

Ask.

Why do you have access to food, in a country that constantly generates news that says that there is no pork, that there is no milk, that there is no rice?

Where does restaurant food come from?

Answer.

I have access to food because I am dedicated to the tourism industry in Cuba.

The people who are dedicated to tourism services are in direct contact with the tourist, with the money, with the

cash

.

Q.

So in Cuba there is food.

A.

In Cuba there is food.

The thing is that there is little access for most people.

At the grocery store on 19th and B, which is the main place where I buy things, there is always pork, at expensive prices but which for me are super affordable.

There is always mutton, and all the vegetables you want are there.

Q.

And when people in Cuba talk about food crises, about not having food, is it that people don't have money?

A.

Most people do not have the money to have access to these products.

Q.

But sometimes people complain that even with money they can't get it.

Isn't it like that for you?

A.

No. I differ there, because you have access to food with money.

Now, if you want to have the market that is outside of Cuba, you have to go to another market to have the variety of things you need.”

It could be said that Grados, a paladar that opens for lunch from 12:00 to 15:00, and for dinner from 19:00 to 22:00, with capacity for 30 people, is a space that was born from the Obama spirit, and that took shape in the era of Donald Trump.

In March 2016, before concluding his term, Obama visited Cuba, the first president of the United States to do so, in the midst of an effervescence that brought to Havana high-level artists, businessmen, entrepreneurs, models who had their portraits taken in front of them. of the destroyed curtain of Old Havana.

It was a time when businesses opened that were supported by the arrival of tourists from all over, who helped diversify the Cuban economy.

But Grados opened in August of the following year, with Trump in the presidency and, consequently, with the withdrawal of many of the policies that Obama had implemented, including travel by American tourists.

Then Cuba, like the rest of the world, was hit by the coronavirus pandemic, was the scene of an unprecedented movement of citizen protests in 2021, and is now going through a post-pandemic context with a strong blow to tourism, a sector that has not yet been able to recover.

“I, in my optimistic thinking, today see Cuba better than ever,” says Raulito.

“Because I saw it worse than ever in the pandemic.”

Even so, if I ask you to tell me what the profile of the Grados customer is today, where a person needs at least 30 dollars to eat, the laziness will be evident.

“It's sad, because today the Grados customer is different from what it was four years ago.

Before the pandemic, I had a clientele that was 60% local and 40% foreign.

Today almost 85% are foreigners.

“Many of the people who came were from a community that emigrated en masse.”

—Do you also want to leave Cuba?

—I don't want to think of Cuba in those terms.

I have always been able to leave Cuba and I don't want to think of Cuba as the place where you have to leave.

The day I think in those terms, I think I will completely lose the fight.

Grados is profitable, but not by much, according to Raulito.

Between six and eight people visit the place daily, who sit down to taste the menu served to them by the food shaman.

Raulito has put an idea into each of his dishes: the green-eyed blonde (corn flour, fried quail egg, avocado and banana), lamb and Prú (grilled lamb with a prú sauce, a popular drink eastern Cuba), the mulato secret (a cut of meat like the Iberian secret, but with mixed-race pigs), or fish and oil.

“Fish and oil is not a recipe, it is an idea,” he explains.

“We make the fish over charcoal and a dark black sauce with cuttlefish ink and black beans.

We accompany it with a piece of plastic collected from the beach.

I go to the beach and start collecting plastics, we wash them and put them on the plate.

The idea is to evoke oil in a sauce and for the customer to take the piece of plastic that the sea returned to them as a gift.”

Raulito created his own drink, which he called basuk, based on ferments and which does not have a single recipe.

He is also the creator of Cuban-American chicken, a dish that, according to Raulito, is a “repatriated chicken, that comes from the United States to Cuba, when most people leave Cuba for the United States.

The chicken does the opposite, and this is a recipe similar to Cajun

street food

in that country, a fried chicken passed through a spicy sauce.

I serve it with a shot of mint liqueur, so that the spiciness plays with the refreshingness of the mint.

Chicken is the main protein that Cubans eat, it is not the best quality, but it is what people are surviving on.

It is paradoxical.”

Raulito will say that his recipes are “the symbols of uprooting, and those that make us a community.”

He likes to work with ideas, textures and colors.

Q.

Do you like Cuban food?

R.

What if I like Cuban food?

I like the food.

Q.

So Cuban food exists, does it not exist, or has it stopped being made?

A.

I think that Cuban food does not exist, because people are not cooking it.

For example, if we talk about the desserts of Cuban cuisine, such as flan, guava casquito with cream cheese, coconut candy with Gouda cheese, rice pudding, people have not cooked that for a long time, it is not in people's refrigerators.

They do not have access to eggs, milk, or sugar.

We know that in 95% of Cuban refrigerators there is no dessert, except on a birthday, at a party.

Here we tend to think about congrí, pork and cassava for December 24 and 31, for the holiday.

Cuban cuisine cannot be two days.

And there are people who don't even have access to that food on those dates.

And if they don't exist in Cuban cuisine, and if people aren't cooking it, you can't say they belong.

It would belong if everyone was cooking it.

If that culture is not being created, that experience in the minds, in the palates of the people, it does not exist.

Q.

We agreed that for you Cuban food does not exist, but did it ever exist?

A.

It exists in the mind, in the imagination, in the collective consciousness.

Q.

If so, do those of us who were born here 60 years ago not know what Cuban food is?

R.

If you say that, people won't like it, but what other way do we have to talk about it? That everything is a fallacy?

To talk about Cuban food being rice and pork on December 31st.

Why only that day?

Why do you force people to do barbaric things?

People don't think of food as an option, as an enjoyment.

The majority, due to lack of access and variety, end up eating a meal full of frustrations.

If you eat a meal full of frustrations, you get frustrated.

For people who have money, it is not for those for whom Cuban cuisine does not exist.

Those people, if they want to eat an okra, they eat it, if they want a fried plantain, they eat it.

If they want to eat a flan and a pudding, they will eat it.

Q.

And what are people eating the most today in Cuba then?

A.

A lot of pizza, the 10 peso pizza.

Cuban pizza has been created.

The pizza business continues to do well.

Those places are full of people.

Q.

If we had to define the quintessential Cuban dish...

A.

It would be the 10 peso pizza.

With his work, Raulito says, he seeks to restore himself and others, even though he knows that the kitchen is a place of violence.

“A place where a lot of violence is constantly generated,” he insists.

“One of the most visible is the violence that eating dead animals represents.

You're working with corpses.

The work team suffers physical violence, from standing for many hours, always carrying things, always exposed to humidity, fungi, substances, breathing or touching cleaning chemicals, scrubbing, or the violence of when you cut yourself, have "You have to work with highly dangerous tools such as grinders, laser machines, knives... You have to expose yourself to fires, fumes, burns from candy, burns from candles, or being burned by a member of the team because they were not careful," he says. .

However, Raulito will also say that cooking helps him release the anger, the annoyance, the sadness of seeing his friends leaving the country en masse.

“I cook sadness and give it to another transformed person.

Even though I feel like this, I feel like working.”

Q.

What do you not like about your job?

A.

Many things that I later end up accepting, especially the contrasts.

I provide an elitist service, and I serve elitist food, and the places where I get that food before transforming it are places that are in misery.

Q.

If I mention everyday words in Cuba like “resolve,” “fight,” “invent,”… do you like them?

A.

Yes, I am friends with them.

Q.

Do you stand in line?

A.

No. I try not to do them.

Q.

Could Cuban food change?

A.

Cuban food will necessarily incorporate many foods that will be defined by the market, the ease of production.

Q.

Your favorite food?

A.

The ice cream cake.

Q.

Your favorite ingredient?

A.

The water.

Follow all the information from El PAÍS América on

and

X

, or in our

weekly newsletter

.