Enlarge image

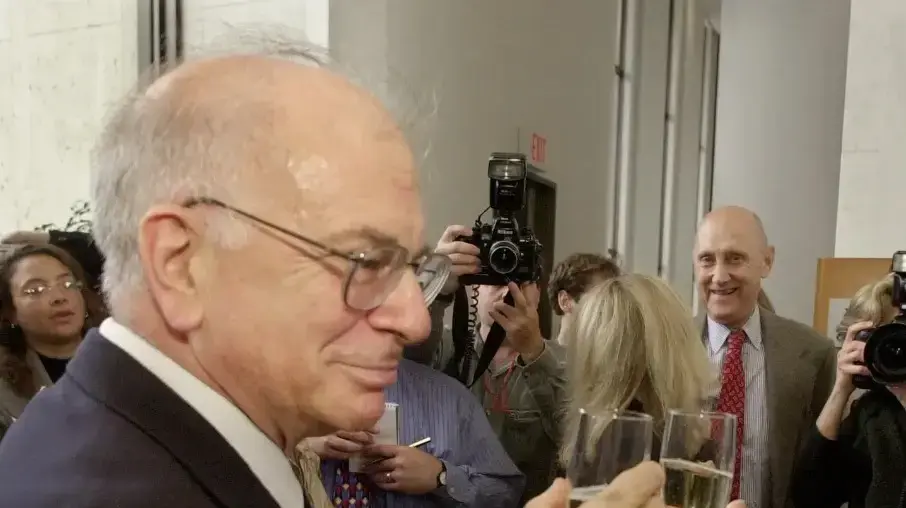

Svante Pääbo (recording from 2010)

Photo: Frank Vinken for Max Planck Society / AP

At the beginning of Svante Pääbo's scientific career, which is now being celebrated with the Nobel Prize for Medicine, there is a secret experiment with a calf's liver.

At Uppsala University, he wanted to mummify the organ in a laboratory oven in order to then research how the genetic material contained therein survived the procedure.

The experiment was "top secret for fear my professor would think it was nonsense.

Unfortunately, the liver soon started to stink, and the matter blew up,” Pääbo told SPIEGEL in 2014.

'But the DNA was pretty well preserved, so I was obviously on the right track.

At the time, I really wanted to decode the genomes of Egyptian mummies.«

It didn't stop with mummies, the researchers went back much further in time.

Pääbo, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, has spent decades refining methods for analyzing Neanderthal genome samples that are thousands of years old.

The procedures are laborious because the DNA molecule in the samples has been severely attacked over time.

In addition, samples are inevitably contaminated with the genetic material of bacteria.

And when you're working, you have to be meticulous about not contaminating the samples with today's human genetic material, which could happen through contact with house dust.

The experiments therefore take place in clean rooms.

In an interview with SPIEGEL, Pääbo confirmed that he spends 95 percent of his time ruling out errors that are based on these problems.

A 40,000 year old piece of finger bone

Pääbo's work provides a glimpse back to our close extinct relatives, the Neanderthals and the Denisovans.

First, he analyzed the DNA in the so-called mitochondria, the cell's power plants, which have their own small genome.

He was already working on it in the nineties.

In 2008, Pääbo and other researchers presented a complete Neanderthal mitochondrial genome, reconstructed from a 38,000-year-old bone fragment.

2010 that of a Denisovan, a previously unknown human species distinct from Neanderthals and modern humans.

An approximately 40,000-year-old finger bone fragment discovered in the Denisova Cave in Siberia made this possible.

And finally, Pääbo's research team also succeeded in reconstructing the complete Neanderthal genome, which was published in 2013.

He had already published a preliminary version in 2010.

One of the findings: A little of the Neanderthal heritage is still found in humans.

We now know that Neanderthals and modern humans mated - and that some genes from the extinct species survive to this day.

An estimated one to four percent of the genome of people of European or Asian descent goes back to the extinct species.

In fact, genes related to skin and hair that come from Neanderthals are common in today's Europeans.

The awarding of the Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology to Svante Pääbo may come as a surprise.

The award is often dedicated to basic research that has not (yet) led to concrete new medical therapies.

But what does the genetic makeup of prehistoric man have to do with today's medicine and physiology?

The Nobel Committee justifies it with the fact that Pääbo's work has enabled a completely new branch of research, paleogenetics, i.e. research into the genetic material of prehistoric samples.

And exploring the genetic differences between people living today and extinct close relatives forms the basis for finding out what makes us unique as humans.

At around 31,000 individual positions in the genome there are typical changes that distinguish modern humans from Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Exploring them more closely could expand our basic understanding of humans.

In an interview with SPIEGEL, Pääbo said the question was whether something could be found in modern humans that did not exist in Neanderthals.

"Something that made him such a crazy creature."

Because while the Neanderthals hardly developed their stone tools in hundreds of thousands of years and never crossed the sea, modern humans settled on every Pacific island - and even wanted to fly to Mars.

"It's kinda crazy."

Crazy enough to secretly mummify a liver - and then open up a new field of research.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/ZV3HRONFCNGOLA37LDSKYTU2VY.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/MTOHBDDWPFDTPBEOJ4TEBMTRWA.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/WWFMH3RJQFHGDLP4L4JLWOGC6Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/4RITWNCKAZFB3I3MBXYYKH6YDI.jpg)