"July 11, 1941. The weather is quite nice. It's hot outside. White clouds in the sky and a light wind is blowing. Shots are heard from the direction of the forest."

The forest is Ponar, a grove located a few kilometers outside the city of Vilnius.

In peaceful days, the residents of the area used to gather mushrooms and berries there.

But other days tarnished the place.

About one hundred thousand people - the vast majority of them Jews, but also communists, Soviet prisoners of war, gypsies and other regime opponents - were murdered there over the course of about three years.

These words open the feverish notes of a Polish journalist named W.

Sakovich, and document the beginning of the mass executions of the Nazis and their Lithuanian helpers in the Killing Gorge.

Sakovich describes in the chilling chronicle that he wrote down every scrap of information that came to him about the horror stories taking place in the forests, and between one horrible report to another, daily descriptions are pinched - how the world continues to turn, nature continues to renew itself, while behind the trees hell on earth is going on.

The famous line written by Bialik following the Chisinau pogrom a few decades earlier, "The sun rose, the system flourished, and the butcher slaughtered", rings in my head and does not let me rest.

Also in other descriptions of the murder of the Jews of Vilna this gruesomeness appears.

This is also the case of the hymn "It was a summer day" - "Es iz kavo a summer tag" in Yiddish - which was written by the girl Rikla Glazer and spread in the Vilnius ghetto.

The song was an anthem, while Glazer somehow survived.

"I went through maybe a thousand miracles and stayed alive," she once tried to explain.

She escaped death time and time again, became a partisan, arrived in the Land of Israel and started a family here.

Despite everything she went through and saw, and everyone she lost along the way, she chose life again and again.

An extraordinary story of survival.

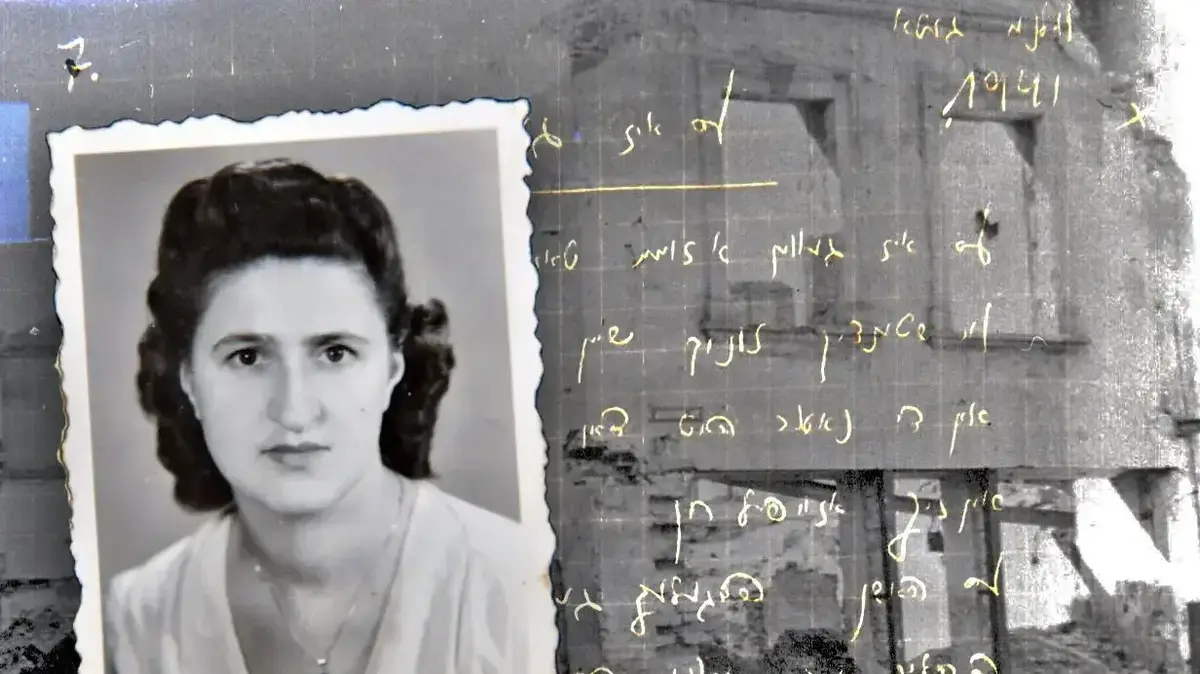

Rikala Glazer (photo: courtesy of the family, reproduction: Reuven Castro)

Rikala Glazer was born in Vilnius in 1924 to her parents Chaya and Yitzchak, scion of a family of goldsmiths.

She also had a younger sister, Nechama (Naqe).

Vilna, Jerusalem Dalita, then part of independent Poland, was a thriving center of Jewish culture, of all types and shades.

Of the almost 200,000 residents on the eve of the war, more than a quarter were Jews.

As the daughter of two literature-loving parents, Glazer was a real bookworm, reading everything she could get her hands on.

In an interview she gave in the early 1970s to researcher Yehiel Shaintoch from the Hebrew University, in which she explained her life story, she said that sometimes she would finish the books even before returning home from the library.

She herself also started writing songs at a young age - 12 or even earlier, according to her testimony.

The outbreak of the World War was accompanied by a series of rapid changes.

On September 1, 1939, Poland was torn between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, and Vilnius was also occupied by the forces of the Red Army.

A month later it was handed over to the Lithuanian state, but within a few more months it was annexed to the Soviet Union.

Throughout that year, many refugees arrived in the city with horror stories about what the Germans were doing.

No one believed them.

Yitzhak and Haya Glazer, Rikala's parents (Photo: Reuven Castro)

The only photo of Glazer as a girl (photo: courtesy of the family, reproduction: Reuven Castro)

The nightmare came true in the summer of 1941, with the Nazi invasion as part of Operation Barbarossa.

Many fled the city, but tens of thousands of residents still remained.

Rikala immediately realized that reality suddenly changed, when Lithuanian violently attacked her and another friend violently in the street.

The mass murder began quickly.

Nazis and Lithuanians kidnapped Jews "for work", and actually sent them to Ponar.

According to various estimates, in the first six months of the German occupation, at least 26,881 people were shot in the Killing Gorge.

At the end of August and beginning of September 1941, the terrible chain of events unfolded, following which the poem was written.

It had already been decided to establish a ghetto in the city, and then the Germans initiated what is known as the "Great Provocation": under the false pretense that Jews had allegedly shot Nazi soldiers in a staged incident, they forcibly evacuated an entire area of its inhabitants, arrested them and deported them to the Killing Gorge in the following days.

Rikala, who happened to be in the area to visit a friend, began to see people running in her direction, running away, but continued until a stranger pulled her aside and told her to go home.

"If I had continued 20 more young people, I would have died already," she said.

At the same time, the Jews of the city were required to enter the ghetto on September 6.

There were actually two ghettos in Vilnius, the central ghetto, the first, and the "small ghetto", which was actually predestined for rapid extermination.

Rikala and her family members were also taken there, until they managed to move to the central ghetto through connections.

In another action in the first days of the ghetto, thousands of Jews were kidnapped and murdered.

Among them were Rikala's father as well as her grandfather and his second wife.

"They said it was for work and everyone believed it," she said.

Baghetto began to process these scenes into songs.

"In those moments... no one knew if he would even stay alive, write so that something would be remembered and the world would know what happened in the ghetto. This instinct demanded that something be written. The feeling pushed me to write. I remember waking up in the middle of the night and writing. I always had writing paper with me And I wrote and wrote. The writing went so fast. The songs came out easily, because I was full of emotions," she said.

And so, about the walk to the ghetto and the mass murder in Ponar, Glazer wrote "It was a summer day" - a heartbreaking poem.

At its center - that terrible contrast between the flourishing nature - and indescribable cruelty.

He begins by describing the beauty: "It was a sunny summer day, as always radiant. Nature looked so beautiful, to the heart with an abundance of grace. Quietly, birds chirped and chirped merrily, to the ghetto a command to go came" (translation: Ephraim Dror).

And in the description of the procession to the ghetto, the picture is completely different.

"It seems, we are on our way if you look - even a bitter stone will cry. An old man and a child were drawn together like an animal to be slaughtered. Human blood was spilled at the head of the street."

The song also describes the other decrees: the overcrowding, and of course the executions.

"The rooms have been emptied, but the graves have been filled" (from another translation, by Binyamin Tana), she writes, "and now objects, hats, wet from the rain are seen on the roads of Ponar. After all, they are the belongings of the victims, of the holy souls, covered forever by the earth."

Finally, nature and murder collide again.

"Now again light and warmth around and fragrances everywhere,

And we are so tormented and silent we will suffer.

Cut off from a seasoned and full, imprisoned in a high wall, and a ray of hope will but hardly break through."

More articles about songs from the ghettos

This is one of the most beautiful and chilling Holocaust songs ever written.

So why does no one know him?

"Show the graves and the names": the song that unfolds the will of the Jews of Kovna

The murder of the children, the hiding in the village and the lost songs: the secrets of "Yeld Yehudi", the forgotten ghetto anthem

"What was it like then Summer Tag", in the handwriting of Rikala Glazer (photo: Reuven Castro)

"What was it like then Summer Tag", in the handwriting of Rikala Glazer (photo: Reuven Castro)

As in many other cases of songs from the ghettos, the lyrics were written on the basis of an existing, familiar melody.

"For me, the songs come spontaneously. A sentence would come out and I would immediately have a melody attached to it, right at the same time. The rhythm of the song came along with the words," said Glazer.

And it wasn't just any tune.

Glazer adapted the words to one of the most famous songs in the Yiddish-speaking world: the song "Papirosen" ("Cigarettes"), written by Herman Yablokoff - a Jew who immigrated to America in the 1920s.

The song, which describes the unhappiness of a boy selling cigarettes, appeared as part of a play he staged in New York, and became very popular in the 1930s.

Although the song is attributed to Liblokoff as mentioned above, he probably also borrowed this melody from an old Russian song called "Moldovian Milsha".

This melody was common in the mouths of Eastern European Jews, and in various ghettos poems were written about it.

"It was a summer day" is the best known of them.

The song spread through children who sang it, and more precisely through one girl - the sister Nechama.

"I was shy, and I read it in front of my friends, but I had a younger sister, who studied in the ghetto at a public school. She would steal the poems. In the ghetto, I would ask her to help me with something at home. She would refuse: 'If you let me read your poem then I'll wash the floor'. [So] she helped and I gave her the poem and she read it in class. She took the poem, brought it to school and the kids sang it, and that's how it spread," Glazer said.

A literary society operated in the ghetto, including many respected poets - Avraham Sutzkaber, Shmaryahu Kacharginsky (author of the poem "Punar") and many others.

Glazer was still a young girl, but her name and her talent spread further, partly thanks to her mother, who read the poems to cultural figures in the ghetto such as Herman Kroc and Kathriel Broida.

She even received an offer to join a literary club in the ghetto, full of none other than Hirsch Glick, a partisan and poet, known as the one who composed the words to the "Partisan Anthem (Don't Please Say Here Is My Last Way)".

In fact, Glazer's testimony hides an unknown story about the moments in which one of the most famous songs of the Holocaust period was born.

According to Glazer's testimony, the melody that would accompany the famous song was found in their meeting.

"Hirsch Glick came to me with another person, maybe he was also a writer, I don't know. His name was Dimenstein... I was reading the poem 'Don't Say This Is My Last Way'... It was during a time of relative silence (she estimated that it was in 1942, but the song was probably written later - NM).

He read me the poem and said: 'How do you like it?

What melody can be added to this?'.

We started singing to the tunes of Russian songs - kazatchki (the name of the song in Russian - NM)... so all the melodies were borrowed from Russian songs."

According to her, "He read me the words and we sang. I don't remember, but I think it was just the melody. Because afterwards he corrected the words to fit the melody. He wrote it in his home. I think he wrote some of the words to fit the melody because he He was not a composer."

At that meeting, Glick complimented her on her poems, and they agreed that she would come to the literary meeting, but it never happened.

Ghetto Saar and more important matters were on the agenda, and Rikala's character also played a role.

"I was very shy, maybe I didn't believe in myself that much. Maybe I was too young."

Rikala escaped death again and again and again.

Lithuanians also tried to kidnap her in one of the campaigns for a truck with children and old people, and through pleading she managed to convince her captors to let her go.

Then she managed to obtain a work permit, and knitted for the Germans, and at another time worked in a brick factory.

Once, after not coming to work, she was banned for one day and received 25 lashes.

The sights around were unbearable, death and murder and humiliation.

The feelings seeped into the songs.

In one of them - "The Song About Jewish Laughter" - she wrote: "We laugh to death with our eyes. Jewish laughter has so much pain in it. When crying doesn't help, then laugh as much as possible... So let's laugh as long as possible. So laugh, laugh brothers As long as there is still a heartbeat. Stifle the pain inside you, even though you are burning inside. May your laughter be heard far away. The day will come when you will laugh from the bottom of your heart out."

In the last promotions she was saved again by a miracle.

Once, after the action had begun and the hiding place where her family members were hiding was already locked, she managed to infiltrate the locked theater hall where the Jewish police were waiting, following a rumor that they and their family members would be taken to Kaunas - where the ghetto was still active at the time.

When she was led out of the ghetto, to the train station, together with the other policemen, she decided to run back and jumped over a high fence.

So she found her mother and sister again.

Rikala Glazer visiting the memorial site in Ponar (photo: courtesy of the family, reproduction: Reuven Castro)

Finally the ghetto was liquidated and they were taken away as well.

"Cars came and loaded us just like animals, while beating us. Me, my mother and my sister got into one car."

It was late, the middle of the night.

The carriage was crowded, but after a while the clicking of the wheels became weaker.

Even without seeing anything, from the trip they understood what the destination was: Ponar.

"The people felt that we were in Punar. They started saying goodbye to each other, kissing, crying and shouting," she said.

"I completely lost my courage. Let them do what they want... my mother told me: hold on to yourself and don't lose confidence. A Jew should go to death with his head held high. It gave me courage, a new soul entered me," she said in her testimony.

Again she decided to take action.

"I raised my head and saw two nurses standing and knocking on the window. It was a small window under the roof of the trailer, and they knock and knock and can't do anything... The window was closed from the outside with a galvanized sheet."

She managed to open it - and jumped out while the train was moving.

She remembered how she fell from a great height and was injured.

Dressed in many layers, with a few individual souvenirs on it.

She wrote about this in another song, "The Wagon of Death", heartbreaking words.

"And when I rise from the ground, a far journey is already echoing. But my ears will be filled with the cry of my son and obituary / And my night will revolve around me. Now what? I will reflect on my blood. And I will pour out: "You are the blood of my wounds, the tears of my mother" (translation: Benjamin Tana).

Rikala Glazer and her husband, Avraham Kaplan, after the war (photo: courtesy of the family, reproduction: Reuven Castro)

Glazer wrote her memories of those moments in a short essay called "I jump off the train", which was translated into Hebrew by her son Yitzhak Kaplan.

"I ran with all my young strength and strong legs. Before me I saw only the iron tracks and behind me endless darkness and the noise of a moving train. In my ears the never-ending shots that wanted to end my young life rang. I no longer cared about anything when I lay in the dark forest, alone and far away The rockets fired from the nearest station of the Germans still flickered in the darkness. After a while I recovered from the shock I was in and looked at myself and realized what a difficult situation I was in... The whole time I was running I did not feel that I was wounded and now with trembling fingers I touched the wound on my forehead, from where the blood spurted and washed away The face and the dress."

She asked herself what she would do now, a wounded girl in the forest without a single friend in the world.

Will she turn herself in?

"No. I have to live!" answers the second voice in my mind. To take revenge on the murderers of mother, father and all the Jews who sought revenge before they sacrificed their lives for the sanctification of Hashem.

She discarded her identification marks, and continued on her way.

One Lithuanian woman let her bathe, eat and rest for a few hours.

Later she caught a ride on a train and managed to return to Vilnius.

On one of the walls she saw a sign: Vilna is free of Jews.

Yitzhak Kaplan, Rikala's son, and the family album (Photo: Reuven Castro)

She managed to get to the Kailis labor camp - a small factory where there were still a few Jews from Vilna left to work, and decided to go into the woods with the partisans.

In order to impress the soldiers at the factory, who did not want to take such a bruised girl with them, she executed a crazy plan: one night she managed to return to the old, abandoned family home, and took out a treasure from the basement - coins, gold, and gold and silver tools that her goldsmith father had buried in the ground before the war, and brought the The spoils for the partisans.

It took its place.

The group went out into the woods, and wandered until they reached the designated place, and again - nature enlightened them.

"When I saw the forest - I felt a great emotion of joy. We are free! The blue sky smiled at us and there were wonderful songs in my heart... The first partisan we met with a rifle on his shoulder instilled in us all a lot of optimism, that we were all intoxicated by the feeling of joy... It seemed to me that everything was singing around me . The sky, the sun and the surrounding green. Now I begin a new life of battle and revenge."

The Jewish fighters were divided into four battalions, and Glazer was part of a battalion called "Death to Fascism".

Among its commanders was Abba Kovner.

In the woods she also met her future husband, Avraham Kaplan, who fled with two of his brothers to the woods from the massacre of the Jews of the town of Voronova.

At some point, non-Jewish partisans also joined them, and they remained in the forests for a little less than a year, until the liberation of Vilna in the summer of 1944. There she began her life anew, and in 1945 her first son, Yitzhak, was born.

She chose life.

Rikala Glazer (photo: courtesy of the family, reproduction: Reuven Castro)

After the war, he met her in Vilna Kacharginsky, who now collected poems from the ghettos throughout Europe.

He asked her for some songs she had written, and indeed: "It was a summer day" is the song that opened the collection of songs from the Vilna Ghetto, compiled by Kacharginsky and published as early as 1947. Since then it has been recorded and received several performances in Yiddish and other languages.

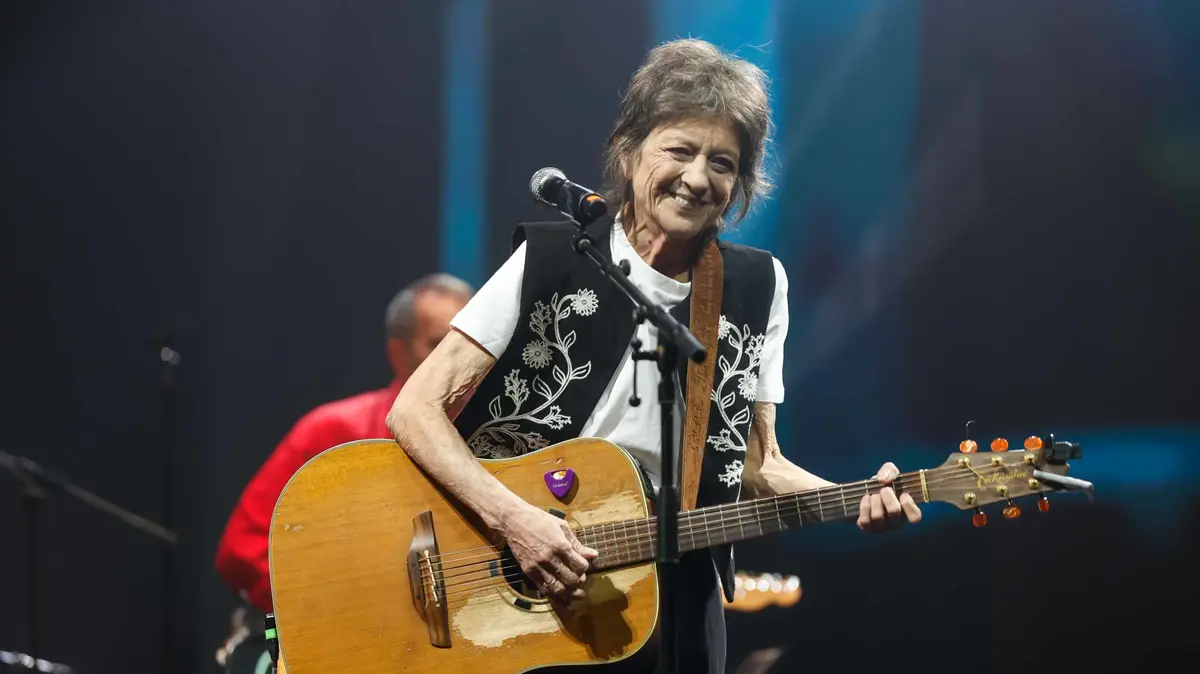

The best known of them is that of Chava Elberstein.

"Vilna ghetto survivors approached me to record songs for a record of ghetto songs," Alberstein wrote to me when I approached her about it.

"I have in my house a song of the songs from there, and I sang 'Zumer-Tag' [by Glazer] and 'Frilling'... and that's the whole Torah."

But Glazer's story is not over yet.

She left Vilna in 1946, on a route that also included the Czech Republic and the Fuking displaced persons camp, near Munich, Germany.

On the way she lost her second son, two years old, who died of poisoning.

During the journey, when they passed under a false identity, she was forced to hand over some of her summaries including the poems - and never received them back.

She arrived in Israel aboard the ship "Negba" in December 1948, and the family wandered until they settled in Holon.

Here too the disasters continued to visit her.

Kaplan, who served in the police, died in 1965 of a heart attack, and he was only 41 years old.

Her third son also died at a young age, still in her life.

Despite all this, her son Yitzhak Kaplan tells me when we meet at his apartment in Holon, that Glazer - here called Ruth Kaplan - was a happy woman who did not sink into mourning.

Surrounded by friends, involved in the community and the focus of every meeting.

She traveled several times to visit Vilnius, and maintained close contact with many of the city's expatriates.

In the 1990s, she published her poems in the book "Lieder von Life", and after her death in 2006, Kaplan dived into her archive, to translate it into Hebrew and put it in order.

Recently her poems were also discovered overseas, and these days they are translating her poems into English.

That way they will continue to live long after her.

culture

music

Israeli music

Tags

Vilnius ghetto

Vilnius

Lithuania

holocaust

Holocaust and heroism day

Holocaust Remembrance Day and Heroism