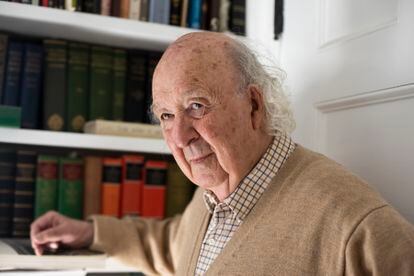

Irish historian Peter Brown at his home in Princeton, New Jersey (USA), on April 29.Joana Toro / JOANA TORO

The fondness for astronomy that Peter Brown (Dublin, 85 years old) developed as a child was a harbinger of the task that was to consecrate him as a historian: the desire to peer into the darkness the points of light that define late antiquity (200-700 after Christ), that period during which the collapse of Rome took place, the religions of the Book took shape and Christianity was taking root in Europe. A period that acquired letter of academic nature thanks precisely to its investigations.

The reissue in Spanish of

The World of Late Antiquity

(Taurus), one of his magnificent works, is an opportunity to rediscover not only that era mistakenly considered dark and its tempting concomitances with the present, but also to review the career of the emeritus professor of Princeton, who previously taught at Oxford, his

alma mater

, until 1975, of the titan capable of rebelling against Edward Gibbon: the thesis of his rupture - the successful but little justified idea of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire - had a radical rereading in Brown's transformation concept.

Revered by generations of historians, the meeting at his Princeton home raises pertinent anxiety.

Like trying to find out what gift someone who has everything wants, what is one to ask a scholar, a sage of international renown?

Such a wealth of knowledge commands respect.

But the courtesy of the professor, who awaits the arrival of the taxi to accompany the interior of the house - bright and placid, with towers of books, porcelain, miniatures and chintz curtains - dilutes any prevention.

“The roots of Europe are also in the Middle East and the southern Mediterranean.

His wealth is his openness to the world "

At the threshold, a side table covered by tiles that reproduce the floral motifs of Iznik, the ceramics of the Ottoman period, makes the visitor appreciate its beauty while pronouncing the place-name. "Iznik!", Abracadabra, predisposes the dialogue. The first reference, thanks to ceramics, is Turkey, a country that Brown and his wife, Betsy, know very well, as an obligatory stop for those who have studied Byzantium in all its forms. Turkey will repeatedly return to the talk. "What do you think of Erdogan? How do you see the situation in the country?", The professor asks later in an exercise in mayeutics. Betsy remembers that Peter studied Turkish, "that language so beautiful, with a beautiful sound," he remarks with delight. He will speak of his vast gift of languages, amused and modest, later. "Now I'm learning Ethiopian," he confesses without giving it any importance."But not the modern, the ancient."

For a total historian like Brown, heir in breath of Fernand Braudel and disciple of Arnaldo Momigliano, how valid is a book written decades ago?

“This book appeared in 1971. Obviously, my concerns have changed.

The reason for dedicating myself to what we now call Late Antiquity was the desire to study a society that had retained its roots in the ancient world, with Latin and Greek as the dominant languages, but had begun to change at the same time.

It was the study of change in an unusually resilient society.

We used to dismiss that period as a period of total breakdown.

We didn't like everything we saw of him ”, he remembers from the time that he epistemologically rehabilitated.

Professor Brown, in the library of his home in Princeton, last April.Joana Toro / JOANA TORO

“That was my main motivation: understanding the exact nature of certain crises, such as the changes in the government of the Roman Empire in the 3rd and 4th centuries. He wanted to find out if they had been disastrous or rather evolutionary adjustment changes; a balance between continuity and discontinuity, fragility and resistance. An example: the emergence of new aristocratic lifestyles in the provinces of the Roman Empire. I owe a lot to Spanish archeology, to the great mosaics of villas like Carranque, which I knew then. Findings that told us: hey, things have not collapsed, they have changed, the focus is no longer on cities ”, the quintessence of the Roman world map along with its road network spread out like a spider's web between metropolises.

"I think one of the main concerns in the field of late antiquity was undermining the easy notion of barbarian invasions," he adds. The temptation to see a transcript of this phenomenon in that of irregular immigration is easy, both for a discourse as blunt as that of the bulk populists and for that other, more complicated, that proposes the perverse theory of replacement. “If you are constantly looking at a false image of the past, looking for the reflection of your own image, it will only lead you down the path of racism, of obscurantism. Of xenophobia. A good example is the barbarian invasions. Everyone is aware that there are problems in Europe due to mass immigration, but it is a terrible historical abuse to treat one as a repetition of the other, ”explains Brown. Furthermore, he adds,"The tragically protagonist jihadist Islam today has nothing to do with that of the prophet Muhammad, with the Islam of 300 years ago, they are totally different."

Julius Caesar killed millions of people.

But do we reject Rome for building on that?

Assuming the shameful part of the past is a sign of maturity.

You are not always proud of your grandfather "

His first book was, however, a biography of Saint Augustine, the North African whom the scholar dismounted from sanctity by titled the work Augustine of Hippo, simply.

“A very Latin figure, a man who represented an immensely oppressive Christianity.

I remember the criticisms in Spanish of my essay;

how Europeans, especially those of Catholic origin, still considered Augustine as part of their own world ”.

Through the intellectual intercession of the saint, Brown overcame ethnocentrism —that is, traditional Eurocentrism, which considers classical civilization as the only source of the West— and was able to look around, another of his great achievements as a historian. “It would have been very easy to continue studying only Christianity, but I came across the discoveries of archeology, I learned Syriac and Hebrew and opened an area whose culture then reached the Greek cities of the Aegean coast, such as Ephesus. They were still impressive cities, but other great works were being created, such as Hagia Sophia in Istanbul ”.

Therefore, he continues without abandoning the use of the plural of modesty and with a very slight occasional, imperceptible stutter, “we saw that there was a world out there and that it could not be written about as if we were to draw the curtain of the Roman Empire;

It was a new life for the Roman Empire, even the Prophet Muhammad and Islam emerged from that culture, they did not come from outer space.

Part of the roots of Europe are not only in Europe.

They are also in the Middle East and the southern Mediterranean.

Part of the richness of European culture is precisely its openness to the world.

In Santa Sofia, in the writings of the Desert Fathers… ”.

Detail of Peter Brown's library at his home in Princeton.Joana Toro / JOANA TORO

Brown is generous in highlighting the contribution of his disciples. He quotes with special affection the Spaniard Javier Arce, or Jack Tannous, his heir at Princeton. For the academic, all research is a great investment: in time, in knowledge, in reading: “Discovering texts, reading languages like Arabic and Syriac fluently, is hard work, which needs additional support. You need institutional support. You need teachers. But once you get it, it can offer you a much richer and broader view than narrow certainties. " So his take on the disdain with which some governments treat the humanities is more than obvious: “[Politicians] are more concerned with the costs of their decisions.We are dealing with a generation of politicians who have long lacked a humanistic education like the one we had. There is nothing more tragic than a man who has lost his memory ”.

On the ordeal of history, lately subjected to the filter of political ultra-correction —the demolition of statues of colonizers or slaveholders, for example, after episodes of police violence against blacks—, Brown —who spent part of his childhood in colonial Sudan, where his father was a civil servant in the British Empire— he maintains: “Not to assume the shameful part of the past is a refusal to be here, to be an adult. Part of adult identification is belonging to previous generations. And like a family, which is not always proud of its uncle or grandfather ... Any mature person must assume the previous members of his family, it is a sign of maturity. A kind of resilience. Julius Caesar is an example. It killed millions of people. And the horrible thing is that we know it because he published it. However,Do we totally reject the Roman Empire because it was based on that? No, we have to apply, I suppose, what we now call binocular vision to focus correctly. " Item plus episodes such as slavery in ancient Rome, which allowed men's sexual access to slaves, and the similar system in force in the southern plantations of the new America, he recalls.

All the ideas that Brown summons in the living room where, in opposite rocking chairs, the talk takes place, can be sharpened, even to the extreme of establishing a direct line between the unconsciousness or the negligence of history and the ignorance that underlies what we call

fake news

. “Forgetting is a tragedy. It can free certain people from bad memories. But I think the problem is half memories. It is not that we have dispensed with historical memory, it is that we have diminished our ability to intervene and criticize false historical memories. It cannot be said that these politicians, the

Brexit

Trump have ignored history, they have simply twisted it.

We know how this has been done in the fascist countries, in the Nazi countries, in the communist countries, today also in the Islamic ones.

Twisting history is even worse than forgetting it.

What is dangerous are the half-memories that politicians use to stoke resentment and fear ”.

Traveling broadens the mind;

history is not just knowing about the past.

That is a narrow view.

It is also about knowing a wider world

Also especially revealing about the hermeneutical validity of the humanities - how they help to understand the world by explaining it - is their experience in prerevolutionary Iran. “I went to Iran in 1974 and 1976, shortly before the Islamic revolution [1979]. The US government wanted to find out what was going on and got in touch with a bunch of professors at Berkeley, but most were development specialists, the great concept that was dominant in the 1960s and 1970s, and they were concerned, of course, with the Present. In the shrine of Mashhad I had a feeling almost of dread, that something very dark and possibly terrible was going to happen. The other professors did not perceive anything behind the facade of a developing country ”. Because a historian is a good journalist, remember an accomplice, just as a good journalist must know the story.

Brown's proverbial gift of tongues - learned Farsi in Iran; Armenian is pending - he supports his insistence on learning “European languages, not only Latin and Greek, very useful for research, but also European languages, without whose knowledge the dimension of the world [in English] is blunt and flat. European culture is a multilingual culture, and Europe's strength is not its uniformity, but its diversity. I am concerned about students who do not read French, German, Italian and Spanish naturally, because they should ”.

How would you convince a high school graduate to study history? “With the metaphor of the trip. If you want to see the pyramids of Egypt, or get to know Seville, why don't you travel back in time? Traveling broadens the mind; history is not just knowing about the past. That is a narrow view. It is also about getting to know a wider world, either now or in the past ”.

At the end of the interview, and while Peter Brown pulls out the car to take the journalist to the station, Betsy Brown respectfully shows, on the corner, the house where Albert Einstein lived while he taught at Princeton.

The conversation ended minutes earlier with an anecdote from Oxford, when the professor gave his students a book in Polish.

"But I also gave them a summary in French," he says like someone who remembers a prank.

The Browns give away a featherweight tour of Princeton which is another history lesson, from the site of the 1777 battle, to the gothic style of

colleges

and rectory.

"Woodrow Wilson [28th president of the United States], who was president," says Brown behind the wheel, amused, "said it was easier to govern the country than the university."

From Marcus Aurelius to Michel Foucault

(Peter Brown in four books)

The world of late antiquity.

From Marcus Aurelius to Muhammad

Peter Brown.

Translation by Antonio Piñero.

Taurus

In 1971, at just 36 years old, Peter Brown published this book which, at less than 300 pages, became one of the most influential essays of the second half of the 20th century. With a mixture of scholarship and audacity, he explains the process by which a homogeneous Mediterranean world ended up divided into three early medieval societies: the Catholic, the Byzantine and the Islamic. Brown showed that the Hollywood "fall of the Roman Empire" had not existed: there was no decline but metamorphosis. And high culture: at this time the "classical language of philosophy" was created through which the Renaissance would rediscover Plato. He also had room to show that the "barbarian invasions" were another anachronism. They had not been "destructive raids and much less organized campaigns",but rather a "gold rush" that pushed the inhabitants of the poorest regions of Europe, which were then those of the north, to emigrate.

Augustine of Hippo

Peter Brown.

Translation by Santiago Tovar, María Tovar and John Oldfield.

Accent

Peter Brown published even younger, at the age of 32, this biography of Saint Augustine (354-430), which continues to be the reference title on the man who, according to some scholars, founded the modern concept of will. Like Saint Jerome and Ausonio, he is part of the third golden age of Latin literature as the author of the "first and one of the greatest self-portraits of all time": "Confessions". Pagan, Manichean, Gnostic, Neoplatonic, and ultimately radical Christian, he perfectly illustrates one of the great tendencies of late antiquity: hatred of the pleasures of the body. It is not by chance that Michel Foucault, author of "History of Sexuality", learned about Brown's book "on the run" (according to Didier Eribon, biographer of the French thinker).Historian and philosopher became friends in Berkeley and in 1982 Peter Brown gave four lectures at the Collège de France which earned him the invitation to participate with 100 master pages in the first volume of the mythical "History of private life", directed by Georges Duby and Philippe Ariès.

The cult of the saints

Peter Brown.

Translation by Francisco Javier Molina de la Torre.

Follow me

"With the serene confidence of those who teach to learn" Peter Brown prepared six lectures for the University of Chicago in 1978. The result, converted into a book, is a fascinating account in which historiography borders theology to the north and theology to the south. fantastic literature. After dismantling the cliché that, originally, the "religious practices" of the elites had little to do with the "superstitions" of the masses, Brown shows that both shared a worship of the martyrs halfway between El Rocío and a "rave party ". With the Roman family home eliminated as a spiritual center for the benefit of public religion, we witness the birth of cemeteries, exorcisms and, above all, the “frenzied trade in relics”. Taking advantage of the Lower Empire network of relationships,the spread of Christianity was not a miracle but, in part, the fruit of the “generosity” of a good number of donors.

Through the eye of a needle

Peter Brown.

Translation by Agustina Luengo.

Cliff

To better understand the hegemonic "construction" of Christianity in the West, Brown tracked money for decades.

In 2012 he published 1,200 pages over two centuries (350-550) that began with the conversion of Constantine in 312 and the subsequent “entry of the rich” into Christian churches to give rise to a “belle époque” of Antiquity that it ended with the sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410. Contrary to the biblical parable of the camel, wealth entered the kingdom of heaven when pagan altruism - oriented to the city - turned into donations to the Church by virtue of the “ love for the poor ”.

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/KTTBFHLHG5EGVAJA3JDPLURK7A.jpg)