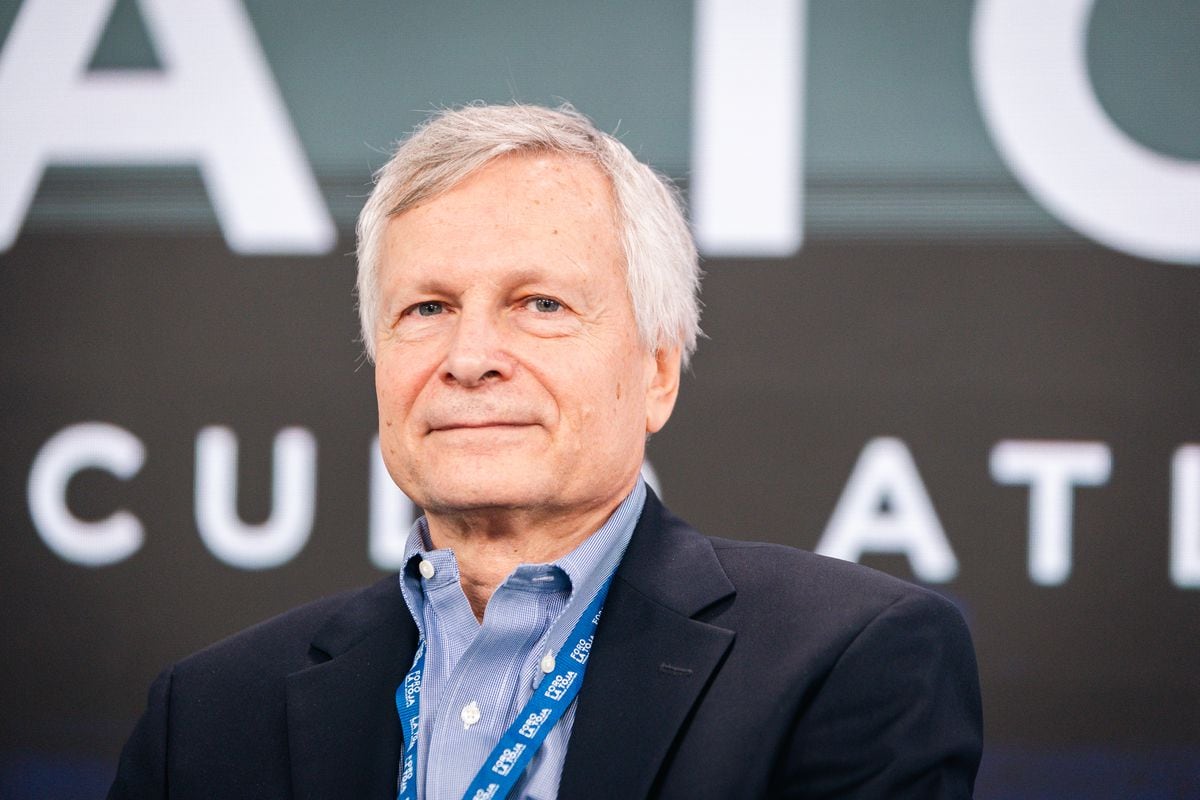

Dani Rodrik (Istanbul, Turkey, 66 years old), professor of Political Economy at Harvard and 2020 Princess of Asturias Award for Social Sciences, confesses that he does not know what globalization will look like in the future, but he has three options: good, ugly and bad. He chooses one depending on how optimistic or pessimistic he rises. In the best option (the others do not want to give much importance), the nations will rebalance their prerogatives in a kind of return to the spirit of Bretton Woods. A rebalancing that, he says, is taking place in the United States with the policy of the Biden Administration. In the worst-case scenario, globalization will continue to be seen as politicians like Bill Clinton saw it, as a phenomenon that cannot be stopped or controlled in which there are a good number of losers. Invited to give a lecture at the La Toja Forum, which this week was held on the island of Pontevedra, Rodrik believes that the US has to give space to China instead of seeking its constant dominance, and warns in turn that the Asian country cannot be subject to the monopolistic dictate of the Communist Party if it wants a modern and diversified economy.

Question. We are seeing times of geopolitical turmoil, climate change awareness, demographic contraction in advanced countries, and labor market resilience despite rate hikes. Has it become too difficult to make predictions?

Answer. Economists have never been good at predicting. An economist I know says that God created astrologers to make economists look good (laughs). There's one thing I feel pretty confident about: we're in a time of transition and the future is going to be different from the past.

Q. In an article published more than 20 years ago in this newspaper, you talked about a globalization where non-democratic countries could not enjoy the same privileges as democratic ones in the field of foreign trade. But it is precisely certain autocracies (especially China) that have led the greatest growth linked to globalization. What do you think about the role China will play in the future?

A. China benefits greatly from globalization. It's largely because he's played by his own rules. It did not play by the rules of many other low- and middle-income countries, for example in Latin America or Central America. China combined its incorporation into the world economy with many policies, such as controlling capital flows; the management of exchange rates or the extensive use of state subsidies and industrial policies contrary to the rules of globalization. We must be careful about attributing China's success to globalization. The overall lesson is that countries that took advantage of globalization and managed their economies did well. China is in a moment of transition. It is now facing problems of great magnitude. The biggest is that its political system is not well adapted to the modern diversified high-tech economy, and that was a problem that I always thought would ultimately play against China. You can't have a modern, diversified high-tech economy with the monopolistic control of a centralized political party. The biggest problem facing China is how its political system adapts.

Q. What do you think of the growing influence that Beijing exerts in Africa, Latin America or even Europe, through trade agreements?

A. As far as international trade and finance are concerned, for the most part we should trade with China as with any other country. After all, trade is a two-way street. We trade with countries not to provide them with benefits, but to provide them to us, and therefore we should not put up barriers to trade with China. I think there are certain segments that involve human rights: what is happening, for example, in Xinjiang; the treatment of some ethnic minorities or the use of cheap labour. But overall, I think China is a growing economy and has become a powerful economy.

Q. How can the inclusive globalization that you propose be achieved if many times (as happens, for example, with the action of the G-20) international agreements remain intentional?

A. The main transition we need is a kind of change or transformation in mindset. 10, 15, 20 years ago the main political forces built globalization as an end in itself and society and the economy had to adjust to it. This is how globalization was presented to the public. I think that brought with it a lot of problems and now we are moving to a stage where we are returning to a healthier understanding of globalization. Global markets meet the needs of our economy and our societies and naturally countries will prioritise their own needs, be it inequality, the need to address the climate transition or human rights concerns with trading partners. The fact that these concerns emerge and become priorities is not necessarily detrimental to globalization, but is a necessary rebalancing. And I believe that if that happens we will have a healthier and more sustainable globalization.

Q. He argues that the international economy should serve the objectives of each country, and not the other way around. But how does that tie up with the climate emergency?

A. There is a very interesting paradox, and that is that if we think of an ideal world, the needs of the climate transition would be sought by nations uniting to establish a global carbon price and also establishing mechanisms for technology and financial transfer to low-income countries so that they are not affected during the process of economic development. In that ideal world there would be enormous global cooperation, but we know that is not happening. We live in an imperfect world, and I encourage action and leadership, whether by individual nations, such as the United States, or by groupings of nations, such as the European Union. The U.S. has engaged in a major program, President Biden's IRA (Inflation Reduction Act), so we have a greater opportunity to solve and address the climate problem because countries are independently designing their approaches to climate solutions, addressing their own political obstacles and designing programs. If we wait for all of them to cooperate globally that's not going to happen, and I think that's the paradox.

Q. What do you think of the results of the BRICS summit?

A. The BRICS have lost their way. I'm no longer sure what they represent. I wish they could become one of the many groups in the multipolar world, because we need a multipolar world. We don't want a world ruled by the United States in a hegemonic way, or in which we confront China and the whole world is left out. I think we will have a healthier world if we have multipolarity, that's always my hope for the BRICS. The danger is that the BRICS will end up being a haven for authoritarian governments in an authoritarian world. I think that would be harmful.

Q. We are at the beginning of a new technological revolution with Artificial Intelligence. How will it affect us?

A. In many ways, it's something that's very difficult to make predictions about, but it's safe to say it's going to have tremendous and very significant consequences. We must not be technological deterministic and make the same mistake that we made with globalisation, which was to say that globalisation is something that falls from the sky and that we can't do anything about it, that we can't shape it and that everyone has to adapt. I think we're going to make the same mistake with AI and the digital revolution saying it's something we can't control. Society has to adapt. We have to adapt and the workers' market will have to adapt. We will all have to acquire new skills, but I think it is also in our power to shape and regulate AI and if we don't, if we don't think deeply about the consequences, they're going to be quite undesirable.

Q. In Europe, the slowdown is not as strong as in China, but the manufacturing sector continues to be affected by weak trade with Asia. Is it good to revive industrial policy?

A. I do not believe that industrial policy can save manufacturing. I believe that industrial policy must be directed towards the green transition. Some, but not all, of these policies have to target industries where productivity tends to be low and where much of the labour force is absorbed. So I think it would be a mistake to think that industrial policy can revive industrialization in terms of increasing the share of employment in manufacturing. We need to be realistic and reorient industrial policy towards new sectors, such as renewable energy and green technology, and also towards where a large part of the workforce is: education, retail, hospitality and care are sectors that we do not normally think about when we think of industrial policy. That's where we really need to think about how we can increase productivity.

Q. Is Europe doing it the right way?

A. Even the most conservative governments pursue an industrial policy, so I think the good thing about reviving industrial policy is that we can participate in a strategic way, and in doing so, I think it is important that we are clear about the objective being pursued: it cannot be the industrial policy of 1960. 1970 or 1980. It cannot be the steel industry or the shipbuilding industry. Europe was always good in these industries, but they're not going to employ many workers. We need to direct industrial policy where it really makes a difference.

Q. Are you more optimistic about the future of the euro?

A. The EU and the euro face a profound structural and existential problem, which is the compatibility of a currency with a single policy. Political power continues to be exercised by different nations. I have been saying for a long time that, ultimately, Europe has to decide whether it wants to maintain a single market with a single currency. For that it will have to find a way to build a single policy at the same time. This kind of thing that the U.S. is doing, experimenting with industrial policy, with different approaches to the labor market, or to confront the power of corporations... that is not possible in Europe. The threat is that Europe will remain a liberal technocracy that is unable to adapt to people's needs.

Follow all the information of Economy and Business on Facebook and X, or in our weekly newsletter

Translation by Luis Enrique Velasco

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Read more

I'm already a subscriber