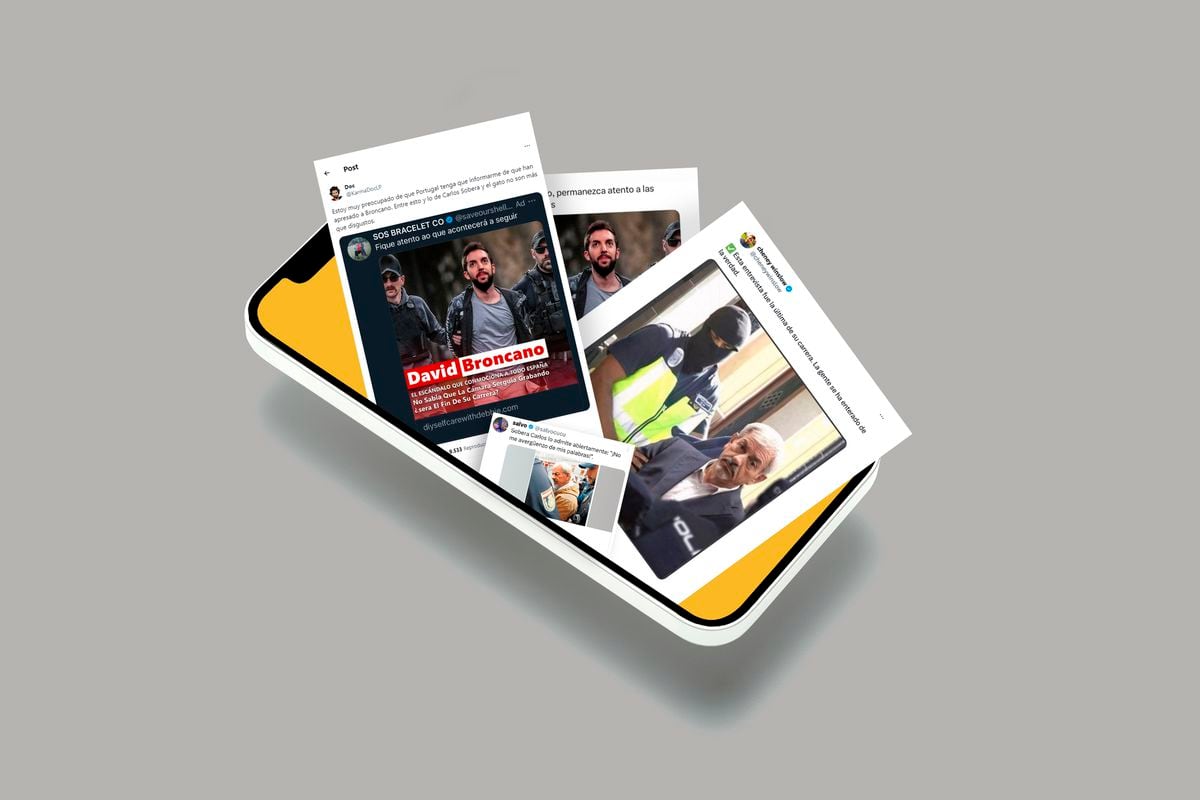

Neither David Broncano nor Carlos Sobera have been arrested “for something you won't believe”; Nor has Laura Escanes been sued for “revealing the secret to earning 300 million euros on an investment platform.” They are hoaxes. In recent months, lies like these have been spread on social networks such as X (formerly Twitter), Facebook or Instagram, through verified anonymous profiles. These publications, which use images of detained celebrities – falsified with artificial intelligence – and shocking headlines seek to direct users to fake news on pages that pretend to be from RTVE,

La Vanguardia,

El Mundo

or EL PAÍS. The objective is to make people believe that a celebrity has spilled the beans and leaked the secret to making a lot of money, and thus lead the reader to an investment portal where they will be scammed.

Removing this type of messages from the Internet, where there are two victims, the deceived and the famous, poses a true judicial labyrinth. To begin with, because behind these websites there is a network of

bots

(fake profiles) and links that appear and disappear. Several lawyers, consulted by this means, point out the obstacles that exist to stop the spread of these messages. “These websites,” explains Luis Ruiz-Rivas García, litigation and TMT (Technology, Media and Telecommunications) partner at Dikei Abogados, “are generated over and over again with different urls [digital addresses], hosted on remote servers for a short time. space of time and which are then replaced by similar ones.” It is a system designed, according to this expert, “to prevent or hinder the identification and geographical location of the perpetrators,” which makes it difficult to “report the facts to the police.”

These are spaces hosted on servers in Russia, the United States, New Zealand, the United Kingdom or the Congo. Teresa Bueyes, a lawyer who is an expert in issues of the right to honor, privacy and image, explains that “these contents violate the right to honor and image of celebrities, which opens the door to a civil claim,” and They also represent “a crime, for using the image of a third party to commit a scam, which leaves criminal proceedings open.” But cross-border judicial bureaucracy muddies their pursuit. “The experience I have is that the judges' orders and orders to foreign countries to identify the server and the owners are disobeyed most of the time,” says the lawyer.

Platforms like X or Instagram not only allow the publication of this type of content, but they also receive money as it is sponsored content. Can social networks, therefore, be held accountable? The question raises doubts. Javier López, partner of ECIJA, remembers that Law 34/2022, on information society services and electronic commerce, establishes the responsibility of “service providers, in this case social networks, for not removing the contents.” illicit” after becoming aware that they exist.

Sharers of the damage

If the platform knows that these publications are illegal, and does nothing to remove them, it can be considered a participant in the damage. Teresa Bueyes believes that, in cases like this, it is appropriate to ask the judge for precautionary measures and demand “censorship of this type of misleading advertising.” It should be noted that, in Spain, the Press and Printing Law of 1966, still in force, determines the joint liability of the author, the director and the editor for defamatory messages published in a medium. A legal provision that, in the opinion of the expert, could be extrapolated to X.

For Pedro Lacal, partner at Carrillo Asesores, “affected celebrities can send a burofax to the platform to report the illicit and harmful nature of the publication and demand its removal.” If it ignores the request, the way is opened to “demand judicial withdrawal through precautionary measures.” But the lawyer recognizes that given the slowness of the judicial procedures, “the response is not going to be immediate.” And, in any case, if a hoax is detected and blocked by precautionary measures, it is normal for about twenty new false information to emerge over the months. Something similar to the heads of the Hydra: for each one that is amputated, twenty new ones will emerge.

If celebrities or those scammed decide to prosecute the perpetrators, filing complaints can activate international judicial cooperation processes “to try to identify and prosecute those responsible,” explains Lacal, although, again, the operation is complex. First of all, because doing so implies “hiring lawyers in the country where the publications are born.” If the culprits can be identified (a difficult mission), the extradition of the subjects to Spain must be demanded so that they can be prosecuted, which represents a real puzzle of papers and procedures. Secondly, because requests for judicial assistance from the Spanish authorities do not always come to fruition, as the lawyers point out.

Demanding compensation can also be a chimera. If a victim were to obtain a favorable ruling in Spain in this direction - the competent courts are those of the territory where the damage occurred - it is most likely that the resolution will become a dead letter, since demanding payment of compensation to a criminal outside the European Economic Area presents a judicial path with uncertain results. “We must not forget,” recalls lawyer Luis Ruiz-Rivas, “that the entire framework is designed to hide the identity and location of the authors.”

Identity fraud

Creating fake news, slandering a public figure and redirecting to fraudulent investment portals involves committing several crimes. To begin with, there is “a case of identity theft”, explains Javier López, partner of ECIJA, in addition to crimes of “slander and fraud”, and if the victim's personal data ends up on the

dark web,

“a crime of illegal seizure and trafficking of personal data.” As for the damages, we are faced with "an attack on honor, image and data protection regulations." For the expert, there is also a case of misleading advertising.

Follow all the information on

Economy

and

Business

on

and

X

, or in our

weekly newsletter