- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Click here to share on LinkedIn (Opens in a new window)

- Click to email a friend (Opens in a new window)

(CNN) - When questioning an informant about an important drug cartel, freshly baked cookies are not exactly on the list of requirements.

But they don't hurt either, and not for the reason you might think.

Former Deputy District Attorney of the United States, Bonnie Klapper, became famous for having homemade sweets on hand while investigating the North Valley cartel in Colombia in the late 1990s and 2000s. However, it was not a deliberate ploy to attract answers, but a way to show some humanity.

At that time, Klapper and his partners in the El Dorado Task Force, from multiple agencies, worked tirelessly to connect the dots between a New York money laundering operation and the North Valley cartel. At that time, it was believed that the notoriously violent cartel was responsible for approximately 60% of the cocaine entering the United States. As the mother of two young children, one of whom was born with special needs, Klapper found himself baking to get rid of stress.

"I woke up in the morning, there were cookies and I brought them, and fed the agents," he said. “If I brought them to an interview, what would I do? Do not feed the accused?

- The Wall Street Journal: Hugo Chávez ordered several collaborators in the 2000s to “flood the US of cocaine ”

After all, people are people, whether they are trapped in a drug operation or not.

“The best prosecutors put themselves in the skin of the accused. They are human beings, just treat them with the same respect that you would like to be treated with, ”Klapper said from his home on a warm September afternoon. “Everything you do in life has to be fair. He has to be kind. There must be recognition of why people end where they end. ”

The same cannot be said of the demolition of the Norte del Valle cartel. It took more than a decade of stubborn and sometimes challenging persistence, as Klapper and his colleagues cut layers and layers of narcojefes. There were death threats from a drug lord and skeptical superiors who questioned closing the case.

But it was not in its nature, Klapper said, leaving the job unfinished. He was going to follow the money until he could tear down the sign from the top, and he did.

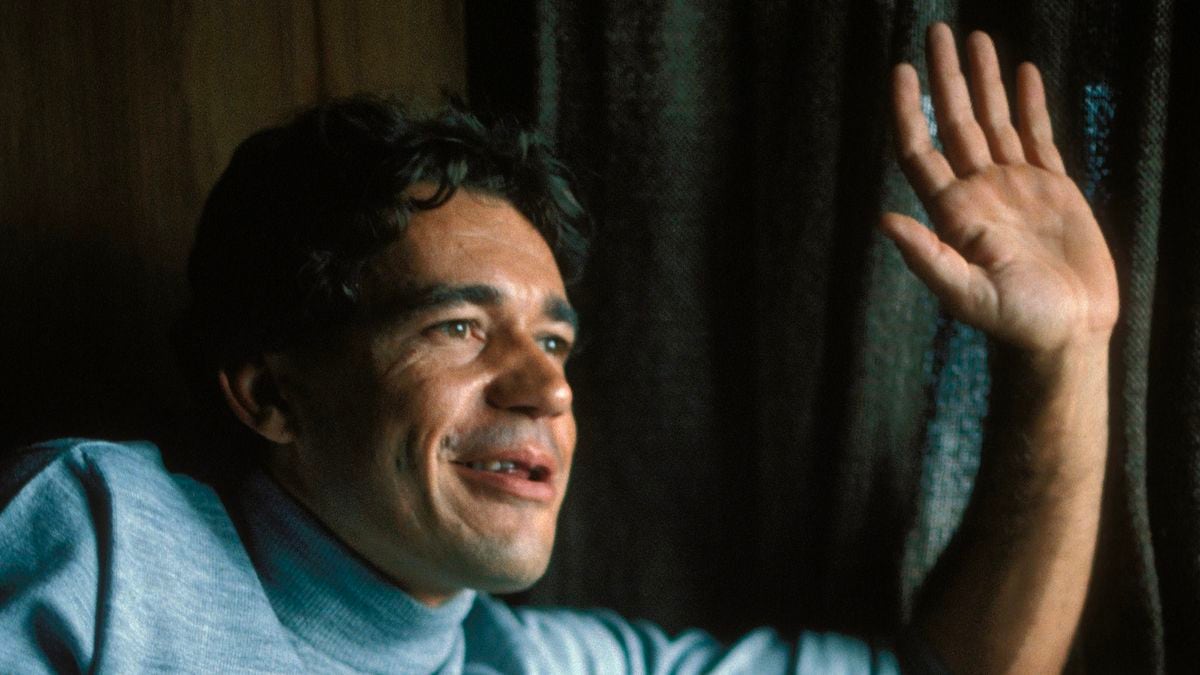

Bonnie Klapper is a former deputy district attorney for the United States.

The road to El Dorado

Raised on the south coast of Long Island in New York, Klapper had always been the girl who wanted justice and was not afraid to demand it. If he got into trouble at school for fighting, it was because he had hit the bully in the class to protect another child.

However, at first, it seemed that the path of his life could be in the arts, or perhaps in journalism. What was always clear was that, whatever the future held, they would find it 4,800 kilometers away from their home.

"I was happy to leave New York as soon as I could," he said. "Berkeley, California, was the antithesis of everything I was raised."

Her father encouraged her to secure her future with an exchange, and she decided on the law. When he graduated from the University of California, Berkeley Law School in 1982, the public defender's office was his first stop, except that they were not hiring. In a short time, she found herself attracted across the hall from the courtroom.

"I saw prosecutors in the United States Attorney's office in Los Angeles, where I was working for a judge, and I saw that they really, at least at that time, seemed to be fair," Klapper said. “And that is a principle that has guided me all my life. Sometimes it has got me in trouble with the bosses, who wanted me to seek unreasonably high sentences or unreasonably aggressive convictions. But if it wasn't right, I just wasn't going to do it. ”

Bonnie Klapper retired as a federal prosecutor in 2012, but still works as a lawyer.

With some perseverance and luck, Klapper joined the United States Attorney's Office in the Central District of California. Soon she was recruited to join her money laundering unit.

Money cases were more difficult, but he discovered that he liked them too.

"How difficult is it to make a drug case at street level?" Says Klapper today. ”In the cases of money, you really had to think, 'Why is it done this way? How can I show the source of funds? ' It is much more sophisticated, and I was simply passionate. ”

Money laundering is essentially finding a way to make funds earned through illicit means appear to have been legally obtained, to make "dirty" money "clean." The cases could become complex, but Klapper had discovered his specialty and his fascination with money laundering came just in time. In the late 1980s, she found herself returning to the east with a husband and a growing family, and the Eastern District of New York was looking for someone with her exact experience.

North of the Valley

When Klapper began working as an assistant to the United States District Attorney in New York, seismic changes occurred much further south.

Colombia had witnessed the bloody rise and fall of the Medellin cartel, which Pablo Escobar had directed with a terrifying force. There was also the Cali cartel, which became even more powerful after Escobar's death in 1993.

However, what some may not realize is that a third Colombian cartel emerged in the 1990s to take the crown as the kings of cocaine. When the Cali organization collapsed in 1995, the Norte del Valle cartel intervened.

As a special DEA supervisory agent puts it in the original CNN series "Decassified", the North Valley was "as bad and unpleasant and formidable as Escobar."

When a war broke out between the Medellin and Cali cartels in the 1980s, the Cali organization gathered a group of assassins to eliminate its rivals.

"Do you know who those individuals were?" The DEA agent continued. "The future members of the North Valle cartel."

But around 1997, when Klapper first heard that suspiciously large sums of money were sent from a money remittance company in New York to Colombia, the name North of the Valley did not appear immediately.

The case was analyzed by members of the El Dorado working group, which included the New York City Police Department, state police, the IRS and the US Customs Service. The task force's job was to investigate financial crimes and money laundering, and they had been informed that something strange was happening at a Tele-Austin outpost in Queens.

The task force began monitoring, and quickly realized that the money transfer business, which, like Western Union or MoneyGram, offers an easy way to send money abroad, was somehow sending tens of millions of dollars in a year to Colombia without the client base to prove it.

"We knew it was drug money because of the volume," Klapper said. “We saw that all the money was going to (the Colombian cities) Armenia, Pereira and Carthage. So, in several legal documents that we present, we call it the Armenia-Pereira-Cartago cartel, because we didn't know what it was. But then, when the first witnesses began to speak, they said: 'Well, that is the North of the Valley.' This is what I really hadn't been on anyone's radar. ”

But what the North of the Valley may have lacked in the press, they severely compensated.

"Nothing touched the level of violence of Pablo (Escobar) because he attacked civilians," Klapper said. "But in terms of retribution and violence, the North Valley had no parallel."

There were clear risks of chasing a cartel formed by hitmen, but Klapper kept his head down and concentrated on work, juggling parents to discover the paper trail.

"My oldest son was born with psycho-neurological disorders," said Klapper. “He has been diagnosed variedly since he was two and a half years old with early onset bipolar disorder, attention deficit disorder (and) intermittent anger disorder. And my husband traveled frequently for work, so it was me. ”

Klapper quickly realizes that, unlike many, she and her husband were able to pay for the help. And while he went deeper into the investigation of money laundering and drug trafficking, the family also relied on the support of the work group and Klapper's partner, Romedio Viola, her working husband, as she jokingly calls him.

"I can't tell you how many times I got the call from the school: 'You need to come to take (your son) home, he's having a bad day,'" Klapper recalled. “Romedio and I got in his car, drove to school, brought him back home, put him on the front of the TV with his snack and worked. I could not have done it without people who understood the situation. ”

However, not all were. There was a boss who told him that a woman with a son like his should not have this type of work, and another who told him that the case of the North Valley was a waste of time.

In response, "I kept doing my job," Klapper said. “We would say that my partner and I were like sharks. We keep moving and we will eventually come across something good. ”

Who fears a headliner?

Like the pieces on a chess board, Klapper and his team were strategically behind each member of the cartel. They did not simply want to close money remittance stores; They wanted to dismantle the entire organization. The plan was to build cases against leadership, extradite them to the United States and have them tried for money laundering and drug trafficking.

Luis Hernando Gómez Bustamante (right) is one of the men Klapper helped apprehend for his connection to the North Valle drug cartel. Here, he is registered by the police in Bogotá, Colombia, in 2007, after being deported from Cuba.

By the end of the 2000s, two of the main leaders of the North Valley cartel had been arrested, and one who remained, a man called "Patemuro," went to look for blood.

“A prosecutor called me and said: 'Bonnie, I think you and Romedio should come here to interview this witness. He's in Miami and says some very scary things, '”said Klapper. “We went down to interview him, and he told us that he had been in the cell block in Colombia with Patemuro, and he was talking about how he was going to kill us, asking someone if they knew the best way to hire a murderer to reach a prosecutor American".

It took months, Klapper said, get protection. But when some agents appeared as his security, they were with her twenty-four hours a day. (No cookies, but they got him freshly baked muffins every morning.)

While Klapper's life had been threatened before, this time it was different: she had investigated this death threat herself, and knew it was real. And yet, during the few months he was under the surveillance of his security team, he says he still wasn't afraid.

"It's like a piece of my brain is missing that doesn't know you're supposed to be afraid of those things," Klapper joked. “I tried to laugh; I thought it was fun. I think I was only scared when the judge pronounced the sentence: Patemuro turned 40, and that was when I realized what we had been trying. I remember crying for two minutes, and then saying, “Good! Let's move on to the next one now. ”

The 'Empress of Money Laundering'

During the many-year investigation, Klapper and his team prosecuted dozens of people in connection with the Valle Valley case, starting from that store suspicious of money remittances to the drug cartel bosses.

"We are talking about more than 50 people, and we only have two fugitives who were not caught," Klapper said with pride evident in his voice.

His persistence in following the flow of money became so legendary that his co-workers gave him a new real nickname.

Klapper, in the center, is shown with Romedio Viola (left) and analyst Sharon Garvey (right). The El Dorado team is still in touch.

"The team of agents I was working with, one of them said: 'You are the queen of money laundering,'" Klapper said, chuckling. "And someone else said: 'No, she is not the queen, she is the empress.'"

While laughing at his sense of humor, he doesn't shy away from the title. According to Klapper, who since then retired as a federal prosecutor and now works in private practice, there were very few agents during that time who addressed the cases in the way she and the work group did.

"The whole case was made based on documents and witnesses," Klapper said. “We had financial records. We had a lot of money seizures. But we never had any drugs. We knocked down a complete poster and never seized a kilo. ”

War on drug trafficking

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/NTCGAD7OXGVJEHGUO75FNHIJXM.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/SUWUS7YYTRADHGYXYQIRE2JO74.jpg)