Lauréline Fontaine is a lawyer.

She has just published

The Abused Constitution

(ed.

Amsterdam, 288 p., 20€).

FIGAROVOX. - The judges of the Constitutional Council are nicknamed the sages. Reading you, we understand that they do not deserve this nickname. For what ?

Laureline FONTAINE. -

The image of the "wise men" has been conveyed by the press and the University since 1959 and the creation of the Constitutional Council.

It developed a lot from the 1990s and still accompanies us in our reading of the system of powers under the Fifth Republic.

It induces a form of guarantee in relation to the way in which power is exercised and, above all, in the way in which it is possibly moderated or limited.

The President of the Constitutional Council himself sometimes uses the image of the “wise men”.

But when we thus convey to everyone the idea that we are a counter-power, there is a lack of wisdom in ignoring the serious faults and the obstacles which affect the exercise of this mission: I demonstrate in my work that the members of the Constitutional Council have

first a chronic problem with impartiality, the rudiments of which they obviously do not master, thus making them "judges and parties".

They also ignore the conditions under which justice can be considered to be done in a democratic regime.

They escape the application of ethical rules, and their remuneration is also illegal (unconstitutional in fact!) for more than half.

In fact, and since in France there is no condition laid down for the quality of the personalities appointed, it is almost always personalities linked to power who are appointed.

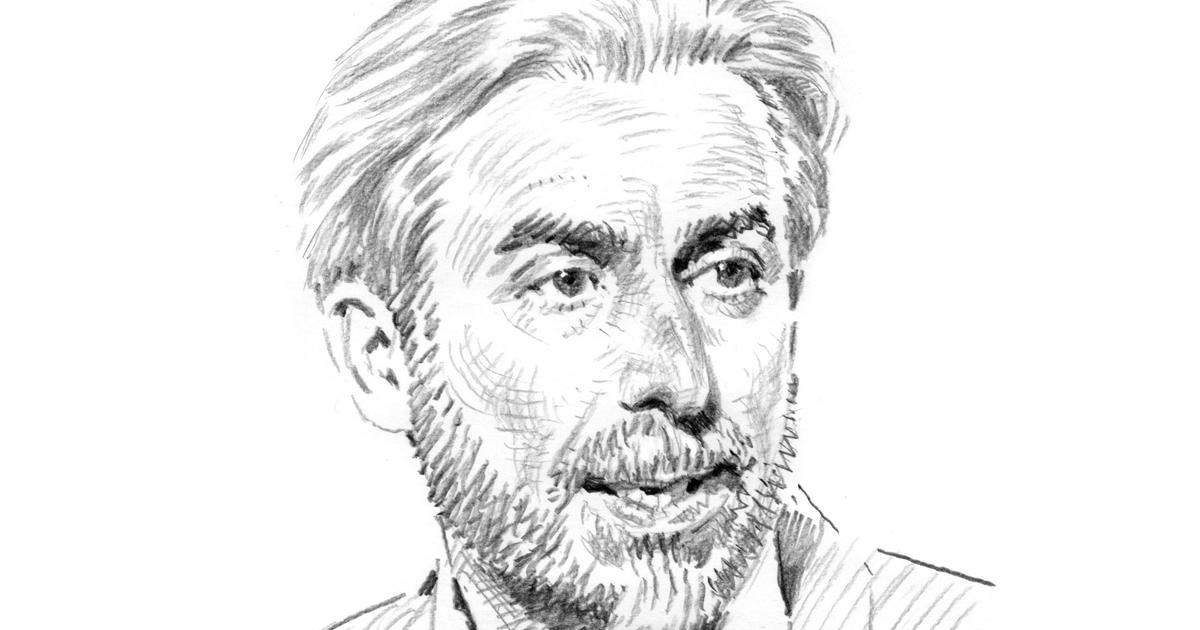

Laureline Fontaine

To complete this sad picture, the work of the Constitutional Council can be considered as very insufficient with regard to the requirements and legitimate expectations linked to its mission: lack of work on the constitutional text which is supposed to serve as its compass, highly problematic loyalty to the powers that it is nevertheless responsible for controlling and finally very great porosity to the influences of economic lobbies.

The maintenance of this situation and the absence of alert for years are not to the credit of those who make up this institution.

Read also“Advance directives: the wise decision of the Constitutional Council”

You point out that, with rare exceptions, the judges of the Council owe their appointment to political favour. Does this pose a problem of independence and impartiality? Can we also speak of a problem of legal competence?

It is true that the appointment system can pose a problem: it is political authorities who appoint those who will control them at their discretion.

As shown by a short tour of the world of constitutional and supreme courts, it nevertheless seems difficult to find a completely satisfactory appointment system.

But on this point attention must be paid to a question at least as important, if not more important than that of the appointment procedure, namely that of the ethics of the appointing authorities.

Since the first appointments in 1959, the President of the Republic, the President of the Senate and the President of the National Assembly have visibly designed the Constitutional Council as a retirement home for loyal and friendly political figures,

more than as a real institution supposed to remind the Government and Parliament of the requirements of the constitutional text.

In fact, and since in France there is no condition laid down for the quality of the personalities appointed (neither age, nor experience, nor specific skills, nor diversity), they are almost always personalities linked to the power that are named.

Those who are for the primacy of the general will which would be expressed in the laws adopted by a political majority therefore have every interest in leaving the Constitutional Council as it is, that is to say not a counter-power.

Laureline Fontaine

Currently, the Constitutional Council is chaired by a former Prime Minister, Laurent Fabius, also former President of the National Assembly, deputy and minister.

Of the eight other members who make up the Council, there is another former Prime Minister, two former ministers and two former parliamentarians.

The long political career of advisers does not at all predispose them to an activity of control of political activity, since "thinking politically", which they have done for several decades in general, is not at all the same thing than to "think about limits to the exercise of power".

It would even be almost a contradiction.

By force of circumstance, the absence of personalities with experience and a habit of thinking about the constitutional text, but above all, the

The current political trend is increasingly to constitutionalize the laws as it could be with the law on abortion. Does this amount to giving exorbitant power to the Constitutional Council? Does it set itself up as a kind of American-style Supreme Court? Should we rejoice in it on the democratic level?

In reality, the constitutionalization of laws is a marginal phenomenon, even if the temptation exists.

What is less so is the tendency of the Constitutional Council to seek the arguments of the constitutionality of laws in these same laws, as if the Constitution said nothing in itself.

The mission of the Council is however to “oppose” the Constitution to the legislator and to the government which would be tempted to leave the nails of the framework which a society considered necessary at a given time.

In the Constitution there are first of all imposed procedures, which until now have been thought of as guarantees for the exercise of a "good" power: for example, the time imposed for the deliberation of the law is the consequence of what

we think that this time is the only one capable of guaranteeing moderate laws and satisfying the interests of the greatest number.

There are also in the Constitution principles and values, like that of the secular and social Republic, which have been deemed desirable as social bonds.

However, in its decisions, the Constitutional Council does not show any particular interest in the meaning of these procedures and these principles.

For example, he prefers to rely on notions such as "general interest", the content of which he leaves to the legislator and the government to determine.

If therefore the legislator and the government claim that they pursue the general interest, the Council does not question this word and confers on it a constitutional value.

It is in the name of the denunciation of a government of judges that there has been no real reform of the institution, and perhaps also that the Council is careful not to use the powers theoretically conferred on it the mission of checking the constitutionality of laws.

Laureline Fontaine

In other words, it is the legislator who himself defines what is constitutional, with almost non-existent control on the part of the Constitutional Council, which does not engage in any real discussion or reflection on this subject.

Those who are for the primacy of the general will which would be expressed in the laws adopted by a political majority therefore have every interest in leaving the Constitutional Council as it is, that is to say not a counter-power.

Those who hope, on the other hand, that the constitutional project be the subject of a dynamic interpretation so that it would not be dependent on the whims and changes of successive institutional majorities, which in reality are not very representative of the social body if we look at the current system of the election,

may have an interest in an in-depth reform of the Constitutional Council.

We should also give it another name on this occasion because, if it can sometimes give its opinion as a "Council", it must above all render decisions that

i “are binding on the public authorities”

according to article 62 of the Constitution.

Read alsoLegislative 2022: the elections of three deputies canceled by the Constitutional Council

Many observers see this as a form of government by judges that would encroach on popular sovereignty. Do you share this point of view?

Obviously not.

As I said, it seems to me on the contrary that the Constitutional Council exercises its mission only in a form of interest clearly understood with power.

The rhetoric of the "government of judges" that we see periodically reactivated, unfolds in ignorance of this reality.

But it is also convenient.

In a Senate briefing report from March 2022, senators questioned the judge's invasion of public life, but acknowledged in the same report that the judge did little to prevent what the policy has decided in recent years.

This means that the government of judges is used as a scarecrow: by acting as if the judge, and especially the Constitutional Council, had too much power, which is not the case at all, we

ensures its neutralization as a counter-power.

It is in the name of the denunciation of a government of judges that there has been no real reform of the institution, and perhaps also that the Council is careful not to use the powers theoretically conferred on it the mission of checking the constitutionality of laws.

Many observers believe that the Council could declare at least part of the text of the pension reform unconstitutional. Whatever one thinks of this reform, is it up to the Council to decide on such a political question?

In reality, the Council is not responsible for making the law, it is responsible for saying, by virtue of the principles and values inscribed in the constitutional text, what the law cannot do, which is not the same thing .

Its mission is above politics, which implies that the will of a majority cannot be sanctified.

If what the Constitution says opposes the will of the legislator, it is up to the social body and the political majority to take their responsibilities: modify the constitutional text, change the Constitution or agree to comply with what was wanted. and thought at one time as desirable principles for the organization of the body politic and social.

When, in 1993, the Constitutional Council struck down a legislative provision relating to the right of asylum,

One can always question the admissibility of the “tactical” use of constitutional procedures which diverts them from their purpose, but at least it is up to the Council to have a serious discussion on this subject.

Laureline Fontaine

If I am not in favor of constant tinkering with the Constitution, it nevertheless seems to me that the process of revising the Constitution is legitimate.

But it should not be confused with the work of the Council, which is to say, at a given moment, what the Constitution requires, whether we like it or not.

With regard to the current pension reform, for example, it should be up to the Council to say that, independently of the assessment of the reform with regard to the principles and values of the Social Republic (Article 1 of the Constitution), the procedure used is distorted: what had been planned to allow a simple control of social security financing operations by the Government (social security financing bills were created with article 47.

1 of the Constitution in 1996) is used for major social reform to avoid parliamentary debate.

One can always wonder about the admissibility of the “tactical” use of constitutional procedures which diverts them from their purpose, but at least it is up to the Council to have a serious discussion on this subject.

However, there is everything to bet that he will answer this question – if he answers it – in a laconic, even authoritarian way, as he almost always does, which I illustrate in my book.

have a serious discussion about it.

However, there is everything to bet that he will answer this question – if he answers it – in a laconic, even authoritarian way, as he almost always does, which I illustrate in my book.

have a serious discussion about it.

However, there is everything to bet that he will answer this question – if he answers it – in a laconic, even authoritarian way, as he almost always does, which I illustrate in my book.

The Constitutional Council is often presented as the protector of freedoms. What do you think of its Covid jurisprudence?

It is representative of the strategy of the Constitutional Council which, as a good politician, assesses the general acceptability of its decisions.

The measures taken at the time may well have been very regressive in terms of individual and collective rights and freedoms - on this point there is little discussion - on the basis of which our political society saw fit to build itself, there was all the same a form of social acceptance of the measures then taken by the government and Parliament.

The Council, which did not want to stop power (but then what is the use?), even went so far as to admit a manifest violation of the Constitution without presenting any argument and basing itself on the apparent common sense that it did not bother to explain (decision no. 2020-799 DC of March 26, 2020).

The problem is compounded by the fact that the drafting of the decision reveals neither the violation of the Constitution, nor what is at stake in this violation, nor the result of this violation.

Reading it, you don't see at all what's going on... and so it happens on its own.

Despite the fact that regressions in terms of rights and freedoms are unfortunately not only characteristic of the Covid period, the Council is even less attentive when the period lends itself to it more.

This is not what we are supposed to expect from a counter-power, guardian of the Constitution in force.

Despite the fact that regressions in terms of rights and freedoms are unfortunately not only characteristic of the Covid period, the Council is even less attentive when the period lends itself to it more.

This is not what we are supposed to expect from a counter-power, guardian of the Constitution in force.

Despite the fact that regressions in terms of rights and freedoms are unfortunately not only characteristic of the Covid period, the Council is even less attentive when the period lends itself to it more.

This is not what we are supposed to expect from a counter-power, guardian of the Constitution in force.

In recent years, France has notably distinguished itself by sharply criticizing Poland for having placed its Constitutional Court under political supervision. Are we in a good position to teach Poland or Hungary lessons in the rule of law?

Let's say that it is not because there is worse elsewhere that it clears us of an awareness of what is happening at home.

The situation of constitutional courts in several countries is disastrous.

But it is visible, in particular because the European institutions and other countries are pointing the finger at this situation.

Our situation is not enviable, however, but it is silent, whereas the process at work for several years, in Poland or Hungary for example, should on the contrary encourage us to be much more vigilant and not to accept this which should not be: a counter-power which is not one, and a functioning of our constitutional justice which is not in conformity with the elementary principles of justice in a democratic regime.

If today we accept so many breaches of the mechanisms of the rule of law, a concept that is admittedly old-fashioned for some because it obliges us to respect the law, to what extent can we be sure that there is a bulwark real to the deployment of a more authoritarian and draconian power?

By constantly undermining our rule of law, we open ourselves up to problematic forms of the exercise of power.

It would be time to notice it.

we open ourselves up to problematic forms of the exercise of power.

It would be time to notice it.

we open ourselves up to problematic forms of the exercise of power.

It would be time to notice it.

The Abused Constitution

, Lauréline Fontaine, ed.

Amsterdam, 288 pages, €20.

Amsterdam Editions