The murder of the children, the hiding in the village and the lost songs: the secrets of a "Jewish boy", the forgotten ghetto anthem

A death sentence hovered over the children of the Shawli ghetto, and its occupants tried to find refuge for them in Lithuanian homes.

The story of "Jewish Child," the best-known poem written there, is the key to the affair: the pain of the parents who abandoned to save their children, the complex relationship with the former neighbors, and also one sensitive poet who was forgotten

Nadav Menuhin

27/04/2022

Wednesday, 27 April, 2022, 10:48 Updated: 10:50

Share on Facebook

Share on WhatsApp

Share on Twitter

Share on Email

Share on general

Comments

Comments

Most of the music is there and sounds, but the survivors of the Shawli ghetto in Lithuania especially remember those produced by the violinist Baba Haimovich.

It is said that by playing in the ghetto he helped to make the patients forget their pain, and the rest - the terrible reality around them.

At a Hanukkah party held in the ghetto in 1942 by the Zionist organization Masada, after lighting the candles and speeches, it was the violinist's turn.

Dressed in his best clothes, and with a trembling hand, he took the violin and began to play.

"He felt it was a big hour in his life," described one attendee, writer and journalist Levy Shalit, who seemed to have forgotten that the violinist played where he played and under what circumstances - and so did the audience, who asked him to keep going.

Along with familiar songs from the past, Baba also played some of the songs written in the ghetto.

Such were in abundance.

"The language was too poor to express everything in prose ... there was a desire to express the pain and this was done in short lines laden with songs, whose sad melodies were immediately found for them and it was easy to pass from person to person," Shalit wrote.

Among the songs played that evening was "A Jewish Child," written by Hanna Hayitin, a young woman from the ghetto.

The poem, about a mother who leaves her son in hiding with Christians in a small Lithuanian village, is the best known of the poems written in the ghetto, in which a perpetual death sentence hovered over the heads of children.

In this simple song lies the terrible tensions of time: the parents who are forced to separate from their young children in order to save them;

The complex ties with their Lithuanian compatriots - what are collaborators, and what are Righteous Among the Nations;

And the knowledge that evil does not stop lurking even after concealment.

Behind the poem hides also one of the most horrible episodes of life in the ghettos - the birth decree, and also the disappearing story of one forgotten poet, in whose words she described it all.

Shauli, also known as Shaul or Shiolai, is located in northern Lithuania.

For the thousands of Jews who lived there - about 6,600 in the early 1940s, a fifth of the total population - it was a city with a vibrant Jewish life, spread across all streams: from Agudat Israel, through the Zionist movements to the Bund and the Communist Party.

But this fabric of life deteriorated with the outbreak of World War II, first with the annexation of Lithuania to the Soviet Union following the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, and later with the Nazi invasion of the Soviet territories in the summer of 1941. Shauli was already occupied on June 26 of that year.

The murder and decrees against the Jews began immediately.

Two months later, on September 1, the remaining 5,500 Jews and many refugees from the surrounding towns were taken into the ghetto, where they lived in great density.

During the first Aktion in the ghetto, six days after entering it, 47 children from the orphanage that operated there together with the teacher and the farm manager were taken and murdered.

It was only the first step in a horrific series of murders against ghetto children.

A city with a bustling Jewish life.

Beshawli Street before the war (Photo: Official website, Yad Vashem)

Among those entering the ghetto were members of the Heitin family: Father Raphael, who owned a brush business, mother Bila, who was a housewife, and sisters Leah, Hannah, Liova (Haviva) and Esther.

Another brother, Hirsch, escaped east to join the Red Army, and was apparently killed at the front.

According to Hannah Haytin, Father Raphael himself perished in the ghetto from hunger and exhaustion.

The other daughters of the family - the mother and the four sisters - remained close, and always remained together throughout the years of the war and its hardships.

Hannah Haytin, born in 1918, was a young woman at the time.

She had previously been trained as a teacher at a seminary in Kaunas.

Like the rest of the family, she also knew Hebrew fluently.

Hannah returned to the city when the war broke out, and entered the ghetto with her family.

In almost every bundle of memoirs written about the ghetto, Haytin is mentioned as "the poet of the ghetto," and her poems accompany them - but there is almost no one to tell about herself.

In fact, apart from a few short articles in which she told a little about her experiences, the main testimony she left behind consists of the same poems she wrote over three years in the Shawli ghetto.

The Heitin family, immediately after the war: Hannah (bottom right), and clockwise the mother spent, Haviva and Leah (Photo: courtesy of the family)

Hayatin began writing songs in the ghetto.

Sometimes she would write in the cubicle where she lived late at night with a tiny light, after everyone had fallen asleep, and sometimes - in the brush factory where she worked.

"Every day I took a pencil with me and a few sheets of pages," she later told Pervert readers.

And there, next to the factory machines, "the thoughts were running at a frightening speed in my head. So I wrote, and I couldn't stop my pencil from writing over and over and over."

The pages were hidden, and for a long time almost no one - except her kind sister - knew about the songs.

Once, during a food break at the factory, she took the sheets with her and then her co-workers found out about it.

The workers got excited, copied the songs and read in their homes, and so they were common throughout the ghetto.

"Kids would sit outside and sing my songs out loud," Haytin recalled of those articles.

"Even the kids who lived with us would always ask, 'Hannah, maybe you already have a new song?'"

Sometimes Khaytin wrote songs without melody, and sometimes she wrote according to melodies of familiar songs from the pre-war period - Russian, Yiddish or theater songs.

"I adapted new words from ghetto life to the familiar melodies," she explained.

She persisted.

"I would sit all night in a small room, with a tiny light, and write and write. It was not difficult to do that - unfortunately there was a lot of material to write about," she said.

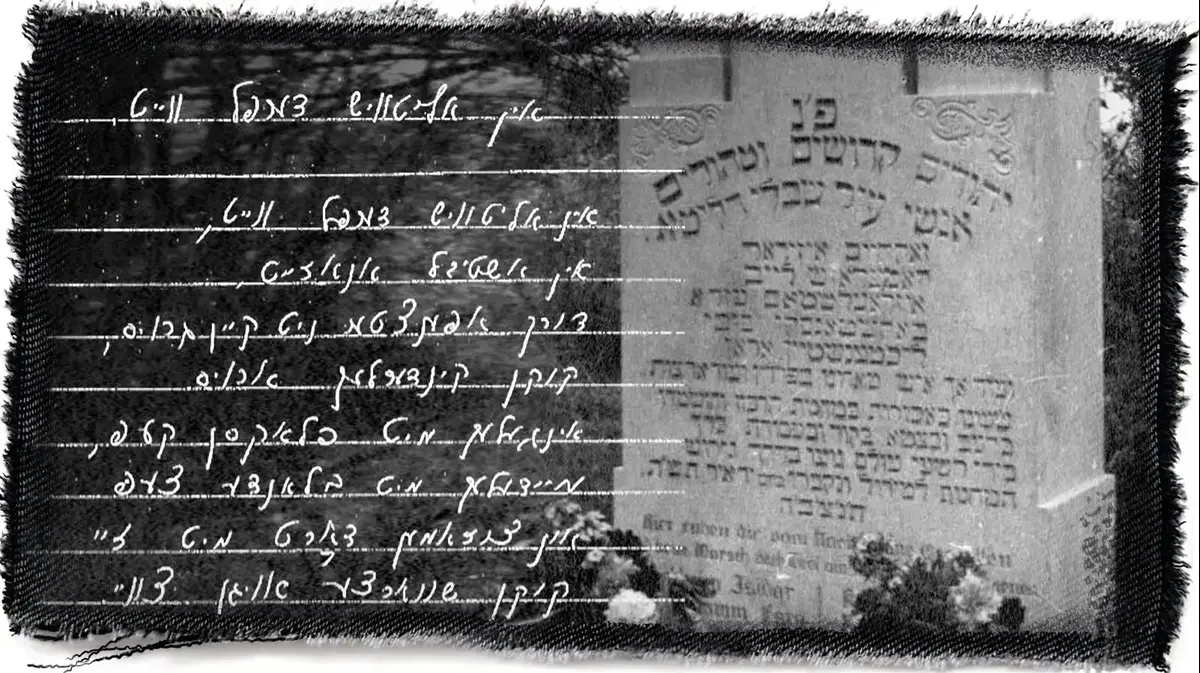

Cover of a notebook by Heitin's poems (courtesy of the Masuah Archive, International Institute for Holocaust Studies, Tel Yitzhak)

"Ghetto Poems Written by Hanna Haytin-Weinstein".

From a handwritten notebook (Photo: Official website, courtesy of the Beacon Archive, International Institute for Holocaust Studies, Tel Yitzhak)

In these songs she expressed a particularly great sensitivity to the pain of mothers and children - to those who lost their children in aktions, and to those who had to hand them over to strangers to save them.

She also wrote about daily life in the ghetto, about going bankrupt to obtain food, and also about events from ghetto life.

Among these events was the execution of Bezalel Mazowiecki, a Jew caught smuggling food into the ghetto.

The Germans forced the Jews to be his executioners, forcing many to attend the class.

According to the narrator, he walked to his death with upright stature and a smile.

Hayatin wrote two songs about the event.

In one of them, dedicated to that last smile, she promised that revenge would come.

And there were also songs of hope.

In another song, "But it will come and the morning will come", Hayitin promises her friends: "Darkness will not forever surround you, it will not darken the night forever" (translation: Samson Meltzer).

A rare recording of the songs of Hannah Hayitin, by the poet herself who reads and sings from them, is in the National Sound Archive in the National Library (at 33:10 in the second file, you can hear her sing "Jewish Child" herself).

More on Walla!

Jordan's Journey, Shapar on the Road to Hollywood, Sabotage: Watching Recommendations for the Eve of Holocaust and Heroism Day 2022

To the full article

Holocaust Martyrs 'and Heroes' Remembrance Day events (Photo: Image Processing, Walla!)

In addition, a notebook of Chaitin's poems and her handwriting rolled into the Beacon Archive.

"These poems are an authentic document of that terrible period, when Nazi murderers and their aides brutally murdered Jews, men, women and children in thousands in all Lithuanian cities and towns and destroyed entire communities. Let us not forget or forget the innocent victims, who died cruelly just because they were Jews. ", She wrote in the introduction to the notebook (translation: Etta Goz-Yankelevich), which she signed with the words:" You must remember forever what the Nazi murderers did to our people. Do not forgive and do not forget - for generations to come. "

In 1942, the authorities imposed a horrific decree on the ghetto residents - as well as on other ghettos within Lithuania: a ban on childbirth.

The expected punishment for mothers and their families was death, and collective punishments also hovered above.

"In 1957, Pharaoh the king of Egypt renewed the decree: 'Every newborn son - and every daughter - everyone must die,'" Levy Shalit described it in his memoirs. The ghetto doctors found themselves in a terrible dilemma: Should they pressure women not to give birth to their children? And how should they act in case of refusal to terminate the pregnancy?

Many mothers have had to have abortions.

In some cases, doctors have had to kill infants by injections and other means.

"In addition to our humiliation and demoralization, we must also experience the punishment of being the murderers of our children," wrote educator Dr. Eliezer Yerushalmi in his diary. Another diary, written by one of the ghetto doctors, Dr. Aharon Pick, mentions several such incidents.

In real time, the details were not known to everyone.

"There were rumors in the ghetto that something terrible was happening to the children

who were born, but we did not know the details," wrote Dov Shilansky, then a boy in Shauli and later Speaker of the Knesset. "Only after the Holocaust did we learn about what happened,

In the basements and upholstered attics, with the danger of death hovering over their entire environment. Rebecca Gotz, who was eight months old and refused to terminate her pregnancy, was one of them. Who cared for him.

Testimony: Hedva Rapaport talks about the Aktion of the children in the Shauli ghetto

In the video: Hedva Rapaport from Chawli, Lithuania, talking about the selection at the children's aktion in the ghetto in November 1943 (Yad Vashem)

The older children in the Shawli ghetto also had a bleak future ahead of them.

It is estimated that there were about a thousand school-age children in the ghetto, and it is not known how many were even younger than that (the boys, from the age of 15 onwards, were already joining the adult work).

Against all odds, the educators in the ghetto set up frameworks for the children, in an attempt to give them stability in the chaotic reality into which they grew up.

In September 1943, the ghetto became a concentration camp, and two months later, on November 5, 1943, the "Children's Aktion" took place there.

574 children were abducted, along with 190 elderly, 26 disabled and four women and taken to extermination.

"At dusk one morning, the ghetto was surrounded by army battalions and the people were not allowed to go to work at first," refugees from the city told a Haaretz newspaper correspondent in late 1945.

"Then the workers were arranged in columns, as usual, and ordered to leave the ghetto. Some guessed what might happen, and there were some who went to work who hid a baby under his coat or basket, but how many could do that?"

A monument to the Jews of Shauli who perished in the Holocaust (Photo: Official website, Yad Vashem)

"After all the working men and women left, Ukrainian cars broke into the ghetto. The SS inspectors handed out bottles of liquor, and after they got drunk, burglars began to snatch houses, kidnap every boy and girl, up to the age of 15-14 and even a newborn baby, and dump him in cars. Some of the children were robbed and destroyed in homes all over the world on their own spirits ... The Optstormpuhrer Forrester [SS officer who served as ghetto inspector - Air Force] walked by the cars, slipped on the children's heads and promised the bitter mothers in tears that no harm Yaona for children;

On the contrary - they are taken to a good life from ghetto life. "The target, of course, was different.

This incident is also etched in Hayatin's memory." It was terrible, scary.

"The heart may explode in the face of this memory, and so may the brain," she later wrote.

"A Jewish Child" ("A Yiddish Kind" or "In a Lithuanian Darf White"), was probably written before the Aktion of the children, but in the memories of the people of the time it is completely identified with that black day, if only because it illustrated that the only way to rescue the ghetto children Was in Lithuanian hands.

The song opens with a description of a little boy, Yossele, with black curls and eyes, who is among blonde, Lithuanian children.

His mother brought him there, and the description of the farewell is heartbreaking.

"From today, my child, this is your place," she tells him, and warns him not to fail in his language: "Do not think Yiddish, because you are no longer a Jew."

Crying, the boy begs you not to go and leave him there alone.

The mother, crying too, still kisses him - but has no choice but to leave, praying to God to have mercy on her son.

At the end of the poem, the boy is again depicted in the stranger's house, silent, lonely and sad.

Meanwhile, the mother does not know her soul for a moment.

Hayatin likens her to Yocheved, Moshe's mother,

This song was also born in the same brush factory.

"I remember how I sang this song for the first time, and everyone sat and cried. People copied the song and it passed from mouth to mouth. They sang it in the woods and in the camps," she later recounted.

The song in the notebook of Hannah Heitin (courtesy of the Masuah Archive, International Institute for Holocaust Studies, Tel Yitzhak)

"In a small village in Lithuania" (Jewish boy), from the songbook (Photo: Official website, courtesy of the Masuah Archive, International Institute for Holocaust Studies, Tel Yitzhak)

Indeed, the song was well known even outside the confines of the Shauli Ghetto.

This is evidenced by the fact that it was first printed two years after the war, precisely in a collection of poems from the Bialystok ghetto.

It soon became widespread and appeared in many collections of songs from the ghettos.

The ultra-Orthodox Holocaust historian Moshe Prager, who collected dozens of poems written during the Holocaust in the collection "From the Strait I Read," wondered about this.

"How did these folk songs spread and spread across all areas of Nazi terror? Not every ghetto and every camp was closed and isolated to itself," Prager wrote. "Beyond the boundaries of the Lithuanian ghettos, although apparently these ghettos had no contact with the ghettos in Poland."

If so, over the years, a "Jewish boy" has given him a life of his own.

It has even been translated into Hebrew several times.

It is also known in Hebrew by several names: "Lev Am", "Jewish child" or "In a small village in Lithuania" (or even "In a small Lithuanian village"

The song was recorded in Israel by several singers.

The most prominent of these is Dorit Reuveni, as part of the record "Songs from the Ghettos" which was released in 1976, in which she participated alongside other singers such as Lior Yeni and Ofira Gloska, and also sang "Ponar" and "The Burning Town".

She told me that this year she will also sing it at the Holocaust Remembrance Day ceremony in Givatayim where she participates every year, after many years of not doing so.

"To me it's the hardest song," she says in a phone call.

"I got along with all the other songs since the album was recorded, but not with this song."

Although she is one of the most experienced singers in Israel, Reuveni says that she has always had a hard time preparing for Holocaust Remembrance Day ceremonies.

"Because of the content of the songs I was not able to memorize them, because I would sit at home and cry with the songs," says Reuveni, "so it was too much for me. I always sing with the lyrics on Holocaust Eve so I have more power, especially in this song.

"It's the hardest song."

Dorit Reuveni (Photo: Reuven Castro)

Reuveni's parents, who came from Yugoslavia and immigrated to Israel before the war, lost almost their entire family in the Holocaust.

"Even though they did not speak, it was always difficult for me," she shares.

When she participated in that record, she was 24. "I was so immature and innocent, and I got such an essay of songs for this album, so I sang simply because I sang but without delving into the lyrics, the sources of the song, where it came from," she admits, and says honestly that " Over the years, from the moment you become a parent then it's even harder to 'sing those songs.

There are several stories about children from the Shauli Ghetto who were hidden in Lithuanian homes.

One of them is the girl Habiba Ziv (later Krasnicki).

She was born in 1940, in the town of Racine where her two parents, Ezekiel and Esther Ziv, lived.

With the Nazi occupation, the Jewish men were taken.

To this day, Haviva does not know exactly where her father was murdered.

Esther's parents and her sister, who lived in the town of Korshan, were also shot dead.

Haviva and her mother rolled as refugees to the Shauli Ghetto, where they lived in terrible overcrowding.

Due to the lack of space, the baby stroller where Habiba slept was placed at the end of the bed where her mother slept.

In those days, Esther worked in the distribution and cleaning of vegetables.

At a certain point, Esther and her sister-in-law Pnina, who also had a child named Yitzhak in the ghetto, also felt the danger posed to small children in the ghetto.

During the children's aktion, she and her cousin went into hiding.

"Pnina took her son and me and another child or two - and hid them in a basement underground," she tells me in a conversation at her home in Holon, "who they [the Nazis] found - they took to trucks."

Towards the end of the Aktion, two Ukrainian policemen who had been brought in to help the Nazis approached the basement window, debating whether to inspect the place in depth.

"They were completely drunk," she says.

Finally, one of them convinced his friend that the effort was unnecessary, and they left.

She hid in several villages.

Haviva Ziv (Krasniktsi) (Photo: Official Website, Yad Vashem)

After the Aktion, Esther decided to smuggle her three-year-old daughter out of the ghetto at all costs.

She hid it in a coat, and left the ghetto in search of a Lithuanian who would be willing to accept her.

"She walked in Shawli from one to the other," says Haviva, until she came to the yard of a seamstress who lived in the city and also employed Jewish seamstresses.

His younger nephew, Vladas Drupas, ran into her out there - he realized they were Jewish, and asked them to hide until the guests in the house left - and then he would come and help.

Drupas had earlier assisted some Jews from the Shawli ghetto to escape from it and find a hiding place.

Drupas and his uncle contacted an acquaintance of theirs, Antennas of Tuzevichius, who agreed to take care of the baby, and until his arrival the mother and daughter were hidden for two days by one laundress.

When Antennas came, he hid her in his coat, and she immediately felt confident.

He took her to the village, to his wife Elena and his family, and Esther returned to the ghetto.

Tribute by the Lithuanian Embassy in Israel to Drupas

"Because of Metozvicius I live. He and his family. There were six children there and he was not afraid to take me. He is a great hero," says Haviva.

"I was a brunette and did not know a Lithuanian word. Later, neighbors said they saw a Jewish girl with him."

Fearing whistleblowing, he transferred her to the home of his sister, Veronica Kilczuskina, who lived in another village with her stepson.

There she learned to speak Lithuanian.

The woman told Habiba that if a stranger came, she would hide inside the fireplace.

"Okay, I'm small, but where are you going to hide?", The girl replied.

Finally, there too they saw her, and then Antennas came again and transferred Habiba to another sister, Juliana and Alyokina, an elderly widow who lived in a small house in a village very far from roads and near the forest.

She told the girl that if her mother did not return at the end of the war - she would adopt her.

A meeting between the rescuers and the survivors.

Seated on the right: Antenna Metuzevichius and Esther Ton.

Standing: Haviva Krasnicki (Photo: Official Website, Yad Vashem)

For a year and a half they did not see each other, but the mother returned.

In June 1944, about a month before the ghetto was liquidated, Esther fled the ghetto with her sister-in-law Pnina, whose son was also hiding in another village.

Metuzevichius and his sisters, and in particular his eldest daughter, Antonina, also took good care of them until the war ended.

After the Russian army liberated the area, they returned to Shawli.

There Esther re-established a family with Yaakov Ton - the uncle of the baby Ben Zion Gutz and who collected him after the war.

A few years later, Reuben and Bella were also born to them.

In her memoir, "Pieces of My Life," Esther Ziv-ton quotes the song "Jewish Child," and mentions Hayitin.

"When I told about the fate of the soft children who were handed over to Lithuanian hands, I remembered her and the sad poetry," she writes.

In July 1944, six months after the "Aktion of the Children," the liquidation of the Shauli Ghetto began.

Most of those who remained in it were still sent to the Stutthof concentration camp.

Apparently, the same violinist, Baba Haimovich, also perished there, along with most of the remaining members of the community.

Haytin, her mother and her three sisters were also among the inmates at the scene.

She stayed there for three months, during which she was forced to dig defense pits for the Germans.

She wrote little there as well, but it was harder to get paper, and she said it was also more dangerous to write.

At the end of that period, she went on a death march, from Stutthof to the south - and also survived it until its liberation by the Red Army, at the end of 1944.

The mother and sisters decided not to return to Lithuania, realizing they had nothing more to look for there.

Only a few hundred of the Jews who were in the ghetto before its final liquidation survived.

The ghetto itself caught fire as a result of the Red Army bombing, which released Shauli.

Then began the wandering journey.

The five women arrived in Lodz, where Sister Esther died of typhus, not long after her release, after being infected by another Holocaust survivor who wanted to help him, and buried in a mass grave in the city.

The mother and three remaining sisters continued on to Italy, where they settled in a DP camp near Naples.

When it came time to immigrate to Israel, Haytin left behind what she had written throughout the war years, and they were never found.

Many of the songs she recalled from her memory.

The Heitin-Weinstein family: father, Hannah and Zvi, 1966 (Photo: courtesy of the family)

In 1945 the mother and three sisters arrived in Israel.

After a first night at Lehavot Haviva, and a short time at Kibbutz Beit Zera, Hayitin finally settled in Ramat Hasharon, where she ran a modest farm with her partner, Abba Weinstein.

They had one son named Zvi.

Many Lithuanian Holocaust survivors came to Ramat Hasharon.

One of the streets in the city, Z. Cheshvan, is even named after the date of the Aktion of the children in the Shawli ghetto.

In the 1960s, in the wake of the severe economic recession, Haytin and her sister Leah (Sharett) and Bnei Bitan decided to leave for the United States, while Haviva (Pianco) remained in the country.

Leah and Hannah settled in Brooklyn - where Weinstein's relatives arranged for him to work in the diamond business.

Haitin, who was a housewife, continued to write songs and stories, occasionally reading from her poems at public Yiddish-speaking events.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, she was a regular contributor to the veteran Yiddish newspaper Forverts.

She died on February 5, 2005 in Brooklyn.

"Poet of the Shabli Ghetto."

Tombstone of Hannah Hayitin, New York (Photo: courtesy of the family)

"She was a very modest woman," says her niece Bilha Mendelssohn, the daughter of the kind sister.

"To me she was a beloved aunt, but I actually broke up with her when I was little. There was a very warm bond."

She says that Khaytin had "her own humor," and that she was the spiritual one between the three sisters.

"Life has given her their blows," she said.

Like many of the survivors, Mendelssohn's mother spoke sparingly about what she went through during the war years.

"For the rest of their lives, they were afraid of dogs, and on Holocaust Day they turned off the television," she said of her parents.

She also learned from the story of Dov Shilansky about the story of the Heitin family in Shavli.

"He was a year above mom at school, so part of his history is also their history," she told me.

Haviva and Leonid Krasnicki (Photo: courtesy of the family)

The Ziv-ton family also went on with their lives.

After the war, it turned out that Ben-Zion Gutz's parents both survived the war, but they reunited in the United States, on the other side of the Iron Curtain, while their son remained with his uncle in the Soviet Union.

In an affair that was extensively covered in the Jewish press, and with the intervention of American diplomats, it was only at the end of the 50s that permission could be sent to send him - then already a 15-year-old boy - to his parents, whom he hardly knew.

In the 1970s, Esther and Yaakov Ton came to Israel, and later all the rescuers they helped were recognized as Righteous Among the Nations.

The realtor, Vladas Drupas, even settled in Israel and lived there for about twenty years until he returned to Lithuania.

Haviva herself remained in Lithuania for many years after most of her family members had already immigrated to Israel.

She worked there as a kindergarten nurse and physiotherapist, and married Leonid Krasnicki, a military man.

They had two children: Raphael and Insa.

In the early 1990s, they also immigrated to Israel with their family members.

She is 82 years old today, and maintains close contact with the descendants of the Righteous Among the Nations who saved her life.

During our meeting in the living room of her beautiful home in Holon, I ask her about a "Jewish boy," and she happily begins to sing it in Yiddish.

"It's just like my story," she says.

culture

on the agenda

Tags

Lithuania

The Holocaust

Dov Shilansky

Holocaust survivors

Righteous Among the Nations

Dorit Reuveni