A question resounds these days with a roar in the main capitals of Latin America and the world: how to alleviate the mess in public accounts? With interest rates on the floor and debt markets still splashing in liquidity, it has not been difficult for the majority of governments in the bloc to finance the bulk of the contingency plans that have prevented the crisis from leading to a depression like the one in the thirties of the last century. But with the worst of the pandemic - it appears - already in the rear-view mirror, the recession in its throes and the world seeing the light at the end of the tunnel, it is beginning to be time to square some numbers decomposed by the virus.

The rise in commodity prices opens an unexpected window of optimism, but the economic recovery will be one of the slowest in the world, far behind the rest of the emerging countries.

And the bloc will emerge from the pandemic, in addition, with more deficits and more public debt than ever imagined: it is already around 80%, not so far from the rich countries.

If before 2020 it was already important to seek new sources of financing from the treasury, after the covid-19 hurricane it is imperative.

The starting point: lagging behind in collection

The virus has finished upsetting the always difficult balance between public income and spending in the region, but the problems were coming from behind.

Especially on the first flank: the average collection does not yet reach 23% of GDP in Latin America and the Caribbean, far - very far - from 34% of the average of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the club that brings together the advanced economies.

The successive rounds of tax increases undertaken in the past decade in several leading Latin American countries, such as Mexico or Colombia, have increased collection by seven percentage points since 1990 and have partially closed that gap.

But there is still much work to be done to increase the incomes of states much smaller than would be expected for their level of per capita income.

The crisis, Biden and the IMF: a triple window of opportunity

Anglo-Saxons use the term

momentum

to refer to the impulse, almost always ethereal and diffuse, that receives an idea at a certain point in time. And that

momentum

now roams in favor of strong states and high taxes after nearly three decades of shrinking the public sector promoted by the global hegemony of

Reaganism

and

Thatcherism

. On the one hand, the crisis unleashed by the confinements has demonstrated the importance of the State when the economic house of cards collapses. In all its aspects: as a breadwinner for informal workers and families in trouble, and as a last-resort support for companies that see their income evaporate overnight.

"The preponderant role of the State during the crisis has become very clear, and one of the great lessons it leaves us is that the countries that have been able to respond best have been those with greater collection capacity and a better social protection system," he draws. Néstor Castañeda, Professor of Latin American Political Economy at University College London. "We are facing a unique possibility of linking fiscal reforms to everything that the public sector has done and continues to do during the crisis," says Diego Sánchez-Ancochea, from Oxford. "But social discontent in the region is such that it is going to demand a redoubled of political pedagogy."

How to return the services provided to the public? There comes the second tailwind. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has shown its most social side, uncompromisingly advocating that the bulk of the bill fall on high income and the most profitable companies. If the region followed the prescriptions that flowed from the Washington consensus for decades and toe-to-toe, shouldn't it now address their demands?

The third comes from the White House. At 78, Joe Biden has come to the presidency of the United States with more desire for

rock and roll

than anyone could intuit. Above all, economically: after dressing up as Roosevelt with billionaire stimulus plans, the Democrat has now embarked on a real fiscal crusade with which he intends to restore the muscle of the public and that goes through tax increases to companies and the wealthiest . "At some point, this new consensus around the role of the State will reach the elites and decision-making circles in Latin America," Castañeda observes. "I don't know how soon, though: technocratic elites are still educated at a previous school and are not particularly flexible when it comes to changing ideas."

Perhaps, confirms Sebastián Nieto Parra, head of the OECD for Latin America and the Caribbean, “never before have there been so many external tailwinds, especially after Biden's tax hike. It is the right time to take advantage of those messages in the region. But, in order to do so, the art of communicating is also more important than ever ”.

The stars have aligned, and this unique combination of factors has opened up a unique space. "But the key, and the difficult thing now, is to be able to take advantage of it," slides José Antonio Ocampo, former head of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and now a professor at Columbia University. He believes, however, that Colombia will end up with a much more progressive reform than was initially proposed. And that Argentina or Chile, among others, will end up following the same path. The pandemic, ditch Juan Carlos Moreno Brid, from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), "was the opportunity for the region's upper classes to see that the health of the richest also depends on that of the poorest." Still, he is not particularly optimistic about an upcoming tax hike: "So far I have hardly seen any movement."

Colombia: a synthesis of the difficulties

Colombia has been the first Latin American country to launch taxes, and its experience does not exactly invite optimism.

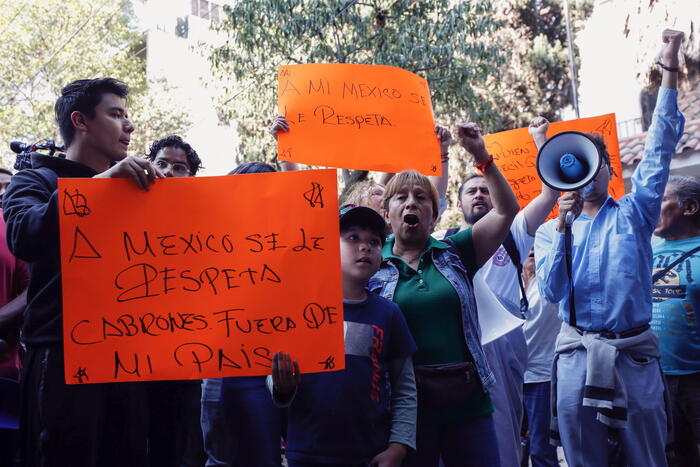

The social protest has forced Iván Duque to drop his initial proposal, which happened - among other things - to tax public services with a VAT of 19% in the upper half of the Colombian system and to include all the workers who earn $ 700 or more among those forced to pay on rent.

Thus, Bogotá proposed to collect the equivalent of 2% of GDP in a series of new taxes to alleviate debt pressures and preserve the credit rating, today in the eaves.

The Colombian government made an effort to highlight the social components of the reform, which also contemplated that the Solidarity Income created to mitigate the pandemic would become a permanent basic income, which would provide the equivalent of between $ 20 and $ 150 per household. The proposal received wide support among analysts and academics, who saw it as necessary. But none of that was enough: it crashed with a massive mobilization in the streets that forced them to turn back.

"I was optimistic when I observed that things were beginning to move in Colombia and I am very pessimistic when I see how everything has turned out," summarizes Sánchez-Ancochea.

An opinion shared by a good number of economists inside and outside the Andean country.

"It is a good example that a reform that had interesting things can end up being a disaster if at the same time it does not eliminate tax benefits to companies and the wealthiest," adds Ocampo.

Demonstrators protest during the national strike against the tax reform on April 29, 2021, in Bogotá, Colombia Ivan Valencia

The rating agencies, on the lookout

Risk rating agencies were sheared out after the 2008 financial crisis, which they failed to see. But a long decade later, its power in deciding which countries or companies do or do not deserve enough trust for investors to deposit their savings in it remains largely intact. In short, their warnings continue to cause earthquakes. And his latest round of alerts exude an intense aroma of concern about the health of Latin American treasuries.

The last one bears the signature of Fitch, which just three weeks ago warned that, without deep reforms that expand collection - bluntly: tax increases - the return of economic growth will not be enough to repair the bloc's public finances. "To stabilize and eventually reduce the burden of public debt requires structural measures and not just cyclical improvements," wrote its analysts.

“The

ratings

are dictating the pattern for you; and without fiscal reforms they could get even worse ”, deepens José Pérez Gorozpe, head of analysis for emerging markets of another of the big companies, S&P, which puts the magnifying glass on three countries: Brazil -” which has carried out the greatest fiscal stimulus in the region and where we already saw weaknesses before the crisis "-, Colombia -" where, as we have seen, it is not so easy to implement a fiscal reform "- and Mexico -" where it is increasingly clear that greater collection is needed " -.

Brazil, by far the most populous nation in the bloc and also the one hardest hit by the health crisis, has been debating a tax reform long before COVID-19 swept everything away. Jair Bolsonaro hoped to have it up and running last year, but the virus took a radical turn in his priorities. "Its lack of definition harms the processing of the reform," explains Felipe Salto, an economist at the Independent Fiscal Institution (IFI). Brazil's always turbulent political arena doesn't help either: the president is under investigation for his possible responsibility in managing the pandemic and his ambition to run for re-election next year leaves little room for unpopular maneuvers. And raising taxes certainly is. As if that were not enough, the Minister of Economy,the ultra-liberal Paulo Guedes stretches the rope to do the opposite of what the public accounts ask for: eliminate exemptions instead of proposing higher taxes.

More information

The OECD recommends that Latin American countries improve the efficiency of public spending

Latin American economies will be unable to fully recover in 2021

ECLAC recommends prioritizing "universal social protection" in Latin America

Andrés Manuel López Obrador is in the ideological antipodes of Bolsonaro, but in the second regional power the debate on the tax reform also navigates in the indefiniteness.

The Mexican economy plummeted 8.5% last year, the biggest drop since the Great Depression, and official forecasts point to a comeback of around 5% in 2021. However, growth in the first quarter was minimal —Only 0.4% —and the pensions and the rescue of the state oil company Pemex multiply the outflows of public money.

With these premises, the president, who had repeatedly refused to open that melon, has already assumed that after the midterm elections in June he will have to take action on the matter.

What is still unknown, at the moment, is the scope of the new legal framework.

"Yes, a tax reform is required in this matter," López Obrador recently recognized in reference to the recomposition of the finances of the different Mexican regions.

His Secretary of the Treasury, Arturo Herrera, has been trying to convince the president for months, but he maintains his refusal to raise taxes, especially those on fuel, to avoid future

gasoline hits

.

A tax system that does not close inequality

Latin America reached the pandemic with the vitola of being the most unequal region in the world, and the crisis has made things even worse: while extreme poverty has skyrocketed to highs in two decades - despite the numerous social lifesavers launched by Governments—, the rich — whose fortunes depend on the future of Stock Exchanges that have already returned to pre-crisis levels — have hardly seen their patrimony eroded.

But there is something even more worrying, due to its structural nature: according to OECD data, the impact of taxes and transfers barely reduces the Gini coefficient - the most popular measure of inequality - by three percentage points, compared to the most 15 points of the European Union average.

In silver: taxation barely corrects the course.

A woman pushes a cart on a Buenos Aires street during the confinement last July.Marcelo Endelli / Getty Images

“It cannot be the middle and lower classes that pay the bill, even less at this time. We come from a great concentration of income and wealth at the

top

, and we should seek a contribution from the richest: once or permanently ”, says Nora Lustig, professor at Tulane University, president emerita of the Economic Association of Latin America and the Caribbean (Lacea) and one of the most prominent economists in the region. "It is a great opportunity, but it will not be easy to take advantage of it: these sectors have many ways of minimizing their tax burden thanks to the mobility of capital." Along the same lines, Martín Rama, chief economist of the World Bank for the region, sees a “clash” of difficult solution “between the ideal and the possible”.

"The debate must clearly revolve around who is going to pay the bill for the crisis," says Castañeda.

“It must be seen in terms of representation: whoever has a better position in the electoral market will transfer the bill to the other groups.

And I am pessimistic, because in countries like Chile, Brazil, Colombia or Mexico businessmen are very well organized, they have a lot of influence in the decision-making process and they seem not at all willing to assume their quota ”.

The ballast of the anti-tax discourse

In addition to being the most unequal region in the world —or perhaps precisely because of that— Latin America is also the one with the highest proportion of wealth in tax havens. According to a study by the Boston Consulting Group, more than three-quarters of the largest assets were deposited in

offshore

jurisdictions

, four times that in Western Europe and - note - 27 times more than in the US and Canada. Although the data dates back four years, nothing suggests that the still photo of this veritable sinkhole of resources has changed much since then.

"Tax reforms are always difficult," admits Sánchez-Ancochea, also author of the book

The costs of inequality in Latin America.

Lessons and Warnings for the Rest of the World

(Bloomsbury Publishing, not yet translated into Spanish).

“But they are even more so if, as is the case in many countries in the region, the elites control the public debate and manage to get the idea that expanding the public sphere only increases corruption.

This anti-state and anti-tax discourse has permeated the entire region, ”he criticizes.

Argentina, a beacon to make the rich pay?

Only one Latin American country has so far launched into the ring of solidarity taxes on large fortunes to make them pay a substantial part of the tax burden that the crisis has brought with it: Argentina. Last December, on a supposedly extraordinary basis and with no provision for continuity in future years, the Government of Alberto Fernández introduced by law a tax on some 12,000 people who declared assets of more than two million dollars. The proceeds, about $ 3 billion, must be used in full to combat the pandemic. “It is a very interesting movement and there are many countries in the region observing that experience to see how it turns out. If there is a moment in which there is a clear justification for doing it, this is it ”, points out Castañeda.

However, the adhesion of Argentine fortunes to the tax was not willing: 220 taxpayers did not comply with the law and brought to justice a tax that, they say, is confiscatory and a threat to private property.

And the treasury, meanwhile, expects a wave of lawsuits among those who did pay: it is common for taxpayers to comply first to avoid fines and then ask for a refund because they consider it illegitimate.

These types of processes usually end up in the Supreme Court, in a process that takes up to a decade.

Against the clock: 12 key months

What happens in the next year will be essential in defining the new regional tax frameworks.

First, because the need to rebalance public accounts is more pressing than ever: all the sources consulted point to the advisability of doing so before the Federal Reserve begins to normalize its monetary policy, a course that sooner or later will lead to a rise in interest rates.

With the

taper tantrum

Of 2013 still on the retina, nobody is aware of what this would translate into in Latin America: investors would tighten the rope, demanding a greater interest in their money and putting the treasury in trouble.

Faced with this situation, the objective cannot be other than to take advantage of the chicha calm and liquidity in the markets to do homework before the curves arrive.

Because they will arrive.

"Today the deficit seems manageable because interest rates are still very low," says Rama, "but if they raise debt service it will complicate things.

The priority is to prevent the current fiscal situation from turning into a crisis;

you have to do something before that moment arrives ”.

"The possibility that, as of 2022, the debate will revolve around austerity and not around all the good that the public sector has done during the pandemic is very great", Sánchez-Ancochea ditch.

The moment is now.

With information from

Enric González

,

Carla Jiménez

,

Francesco Manetto

and

Santiago Torrado

.

Subscribe here

to the

EL PAÍS América

newsletter

and receive all the informative keys of the current situation in the region.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/GI4IKIDOOBFTFHFRXLQ2PGMVUI.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/UEAOTRFT4RAELEX75JUQ32CG5I.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/ZU5KUJFBSRGVVM2SXJTZBZP3XI.jpg)