If the first ascent of Mont Blanc occurred in 1786, in 1860 the sharp figure of the Matterhorn was still causing panic to those who dreamed of reaching its virgin summit.

Its razor-sharp edges and vertiginous slopes were as attractive to the eye as they were repellent to the imagination of the most daring, with the exception of the Englishman Edward Whymper and the Italian Jean Antoine Carrel.

The first had discovered the Alps as an illustrator and had set out to conquer the Alpine peaks with an inordinate appetite and enormous success.

His amazing impulse catapulted mountaineering towards its golden age, numbered between 1860 and the fateful date on which he managed to climb the Matterhorn: 1865. At a time when the English aristocracy and bourgeoisie, inventors of the game of mountaineering,

viewing their guides more as servants than as indispensable figures on their mountain journeys, Whymper found in Michel Croz a mirror, the same passion, and technical skills that he lacked.

He christened him 'the prince of guides' and respected him as an equal.

Croz, born in Le Tour, one of the last villages in the Chamonix Valley, next to the Swiss border, left his trade as a tanner to guide in the summer.

The house in which he was born is now decorated with colorful flowers, a plaque, and a picture of him posing with his pipe and the rope across his shoulders.

His premature death seems to have erased him from the list of great figures in the valley, and this despite the fact that his skill and determination led to great firsts such as Punta Croz to the Grandes Jorasses, the Moine ridge to the Aiguille Verte ,

the Dent Blanche or the Barre des Ecrins.

The place it deserves in history is enormous.

Between 1854 and 1865, 31 of the 39 highest peaks in the Alps were summited by English 'amateur' climbers accompanied by Swiss and French guides.

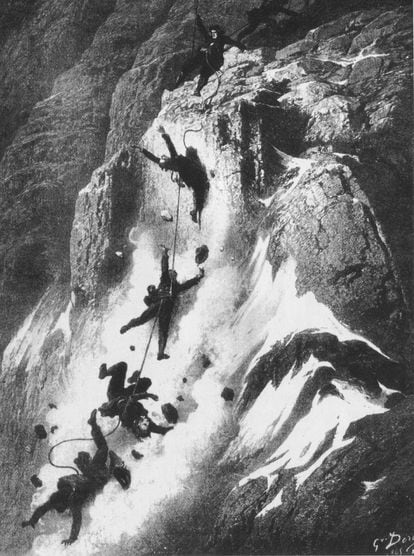

The tragedy of the Matterhorn, drawn by Gustave Doré.

Obsessed to the core, Whymper began to be known as 'the madman of the Matterhorn', and between 1860 and 1865 he made several attempts from the Italian side, with or without guides, until he was convinced of two extremes: he had to join Michel Croz and launch their attack on the friendlier Swiss side.

The first attempt should have been made on July 9 and 10, 1865 by Whymper and the very solvent transalpine guide Carrel.

A previous commitment of Croz prevented him from being in the game.

But bad weather cut short the attack and Whymper found himself alone: Croz had been hired by Reverend Hudson and Carrel, forced by national pride and pressure from the local government, chose the Italian side to conquer the mountain without Whymper.

The 'betrayal' almost drove the English mad,

who, desperate, had the fortune to meet Lord Francis Douglas and the Taugwalder father and son, two Swiss guides with whom he formed a rope.

It was the first competition to achieve the first ascent of a mountain, only at the last minute, the number of applicants would still grow.

In Zermatt, today the exclusive Swiss town at the foot of the famous mountain, Whymper met Reverend Hudson, an excellent mountaineer who was traveling with Michel Croz, interested in discovering the Matterhorn.

Whymper knew deep inside him that Croz was the master key to finally reaching the top.

He convinced the reverend to join his forces and not compete, but Whymper had to accept one last passenger in exchange: the young Douglas Hadow, 19 years old, and who lacked the necessary experience in the mountains, although his physical strength was Awesome.

Portrait of the guide Michel Croz.

For his part, Carrel launched his attack two days before Whymper and his six companions got down to business.

However, they advanced with enormous solvency and on July 14 they reached the top of the Swiss slope.

Just about 100 meters in a straight line was the Italian peak.

Whymper and Croz broke loose and ran, a surreal scene with which they tried to discover some trace of their Italian rivals.

They found nothing.

Looking out into the void, they saw Carrel and his team still on the wall, far away.

To discourage them, they threw blocks of rock at them that forced their abandonment.

Whymper would never have allowed Carrel to reach the top that same day, hours later, so his success was absolute.

After leaving a flag with Croz's blouse as a sign,

The seven began their descent down steep slopes of frozen snow.

Back then there were no crampons or ice axes, or dynamic ropes.

It is still overwhelming to imagine them balancing so as not to fall, using a technique that is as refined as it is strenuous.

Frightened by Hadow's manifest clumsiness, Croz, who should have been riding at the back of the group managing the safety of the line, had to move to the front to carve steps out of the snow again with his ax and properly place Hadow's feet on the ground. safe position.

Behind Hadow descended Douglas and Hudson, the four linked by a solid rope.

Later, a thinner rope connected them with the rope formed by Whymper and the Taugwalders, the father being in charge of securing both groups.

Croz twisted into the void to lose some height and help Hadow again, but Hadow slipped, colliding with the guide and they both fell, immediately dragging the Reverend and the Lord.

Then the unthinkable happened: the rope that linked them to the rest snapped.

Horrified, Whymper would explain to the judge that he saw them slip for a few seconds, arms flailing, trying to cling to some rock ledge before disappearing down the north face and landing 4,000 feet below.

Portrait of the leader of the expedition, Edward Whymper.

The English press picked up on the drama immediately, with headlines like “Homicidal Alps” and the Times calling mountaineering a matter of “apes and squirrel pirouettes”.

The game of mountain climbing had brutally hit its limits, and the novelty outraged both the press and Queen Victoria herself, related to the late Lord Francis Douglas.

No tragedy of this magnitude had yet punctuated a first ascent.

Edward Whymper and Peter Taugwalder appeared before the judge to clarify the circumstances of the accident: Why was the rope that united the deceased with the survivors so thin?

It was undoubtedly negligence, but then it was unknown that a rope could break not only due to friction but also due to the so-called whip effect.

The judge ruled that it was Hadow's fault, his incompetence.

Taugwalder Sr. could not stand the gossip that came to accuse him of cutting the rope and went into exile in the United States.

His son came to guide 125 cervinos.

Carrel climbed the Matterhorn two days later, from Italy.

Sadness and bitterness presided over the last years of Edward Whymper's life.

Ten guides from Chamonix carried his coffin before burying him in the local cemetery.

Michel Croz, on the other hand, is still buried in Zermatt.

You can follow EL PAÍS Deportes on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

50% off

Subscribe to continue reading

read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber