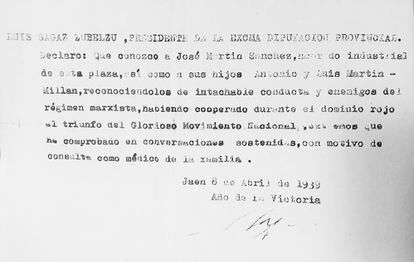

The safe-conduct that saved the lives of the Martín Millán brothers in the throes of the Civil War.

“I wonder how one will feel when one knows that one is walking on the edge of the precipice, on the edge, on the border between life and death.

It must be overwhelming to feel the vertigo of the cliff when you know that a slight stumble can plunge you into the abyss”.

In this way, Luis Martín Mesa expresses the atrocious fear and anxiety that, in his opinion, must have accompanied his father and uncle since one fine day, already at the end of the Civil War, they crossed paths on a street in Jaén with a political commissar of the Regime who asked them: "What are you doing alive?".

More information

Transfer of remains of Francoist leaders, revocation of medals and annulment of sentences: the first measures of the Democratic Memory Law

At that time the executions did not stop in the old cemetery of San Eufrasio in Jaén, so Luis Martín Millán and his brother Antonio predicted that their fate was already cast, it was a matter of days.

And so it could have been if it had not arrived at the last minute, almost

in extremis

, a saving pass that the newly elected president of the Diputación de Jaén, Luis Sagaz Zubeldia, signed on April 8, 1939. That safe conduct is now the common thread of the novel

Café de malta y chicory

(Ediciones Seshat) that Luis Martín Mesa has just published and with which, mixing essay with fiction, he wants to contribute to unraveling a subject that for decades became something taboo in his family.

Both Luis and Antonio Martín Millán evaded the summary process by adhering to the rebellion.

The first could only be accused of having been a replacement soldier for the republican army, while Antonio did come to serve as a commissar for the Popular Front.

However, in the safe conduct, Luis Sagaz, who was a very prestigious doctor and psychiatrist - he came to work with Gregorio Marañón - and who cared for the grandmother of the Martín Millán, had to lie in order to save their lives.

Of them he highlighted their "irreproachable conduct and enemies of the Marxist regime, having cooperated during the red domain in the triumph of the Glorious National Movement", something that, obviously, did not respond to reality.

“My father always said that he would have exchanged a year of military service for three more years of war, and that because of the humiliating and humiliating treatment he suffered when he was forced by the Local Classification Board to do three additional years of military service [he had already done with the Republic] that was nothing more than a training ground to reconvert them into the sole thought of the dictatorial regime”, explains Luis Martín Mesa, for whom his family always wanted to silence this safe-conduct that was received as a relief.

“We were suffering, scared to death, what we wanted was for [the Civil War] to end, no matter how, for it to be over as soon as possible, and when it was over, what we felt was relief, not joy, relief, which is not what same.

(…) In wars I do not know if someone wins, what I do know is that they always lose the same ones, if you are from below you have lost”, writes Martín Mesa in the novel to recall the conversation he had with an aunt of his, which would be the one that would end up confirming the existence of that safe-conduct.

Malt and chicory coffee was during the post-war years a substitute for coffee, good coffee, which was only available to wealthy people.

"The title of the novel is, therefore, a metaphor to suggest that I am talking about the needy people, those from below, the losers," explains Martín Mesa.

People like the grandfather of the Martín Mesa family, who had a soap shop next to Calle Ancha in Jaén, just a few meters from where Miguel Hernández and his wife Josefina Manresa lived for just over a month.

The poet from Alicante had been transferred to Jaén as a curator in the propaganda organization

Altavoz del Frente Sur

with a very clear mission: to collaborate in the writing of war prose and poetry for publication in the newspapers and leaflets of the front.

And even the family of Martín Mesa arrived, on April 4, 1937, a magazine from the

Speaker of the Southern Front

that accounted for the bombardment by the rebel troops that three days earlier had devastated the old town of Jaén, leaving 157 fatalities, even more than those that occurred in the most famous bombing of Guernica.

In that article, Miguel Hernández lamented the passive attitude of a large part of Jaén society in the face of the Civil War: “Few were those who gave importance and credit to the events that were taking place in Madrid and on the other fronts of the struggle, and they were Many of those who apologized and even applauded in the depths of their hearts the criminal introduction of fascism in Spain, had their hearts almost deaf, almost blind, almost insensitive to the generous waves of blood that have been unfolded on the Hispanic lot since July 19 of 1936″.

The bad luck of 200 socialist leaders

Less fortunate than that of the Martín Millán brothers was a group of some 200 socialist leaders who, after having agreed to flee with the Franco regime, were intercepted by a legion of Falangists in the vicinity of Baza (Granada) when they tried to reach the port of Alicante in search of exile.

Only a few managed to escape, but most were taken to the prisons of Granada and, later, to that of Jaén.

They were shot and their remains still remain in one of the mass graves of the old San Eufrasio cemetery in the capital of Jaén, where a group of archaeologists have just started work on the exhumation of three graves where it is believed that there are 1,286 victims of the repression Francoist.

Also in the last days of the Civil War, Dolores García Negrete, widow of doctor Federico Castillo and mother of 23 children, of whom only 11 survived at the end of the War, was arrested.

The woman was imprisoned and executed a year later.

Her death caused a stir among Republican militants, especially among the communists who shared a cell with García Negrete in the military prison of the Santa Úrsula convent for opposing Casado's coup during the Republic.

All these little-known passages of the Civil War are now highlighted in

Café de malta y chicory

, a novel with which Luis Martín Mesa wanted to settle a debt he owed his father.

“It is a way of giving the floor to people like my father who had to keep their mouths shut for so many years due to the imperative of the fascist regime.

He already died, and he owed it to him, ”concludes the Andalusian writer.

Subscribe to continue reading

read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber