Juan Muñoz went around with a knife in his pocket, like a bandit or a common criminal.

It was never clear if this was true or part of the legend about him.

But now the gallery owner Pepe Cobo, who was close, confirms it: "He did it to show himself as someone from the street, an insubmissive."

This is confirmed by his wife, also an artist Cristina Iglesias: “Although from a certain moment on he wondered if the razor was not more typical of a neurotic”.

And confirmed by Manuel Segade, curator and director of the CA2M museum in Móstoles, an expert in his work: "So he changed the knife for a deck of cards, as if sleight of hand were another type of weapon."

Segade is the curator of the two exhibitions in the Community of Madrid dedicated to Juan Muñoz (Madrid, 1953-Ibiza, 2001), perhaps the most international contemporary Spanish artist of the last two decades of the 20th century, on his 70th anniversary of his birth.

The first,

Everything I See Will Survive Me

(a quote from the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova), opens on February 14 at Sala Alcalá 31 in the capital.

The second,

In the violet hour

(title taken from the collection of poems La tierra baldía, by TS Eliot), at CA2M itself, will be held on June 17, the artist's birthday.

Both make up, more than a tribute, a reminder.

And they intend to provide a new look, projected towards the future —which is our present—, on an artist who has almost always explained himself from the conventions of the past.

We are promised, let's say, a new Juan Muñoz.

Although for Manuel Segade it is the same as always: "The usual reading about Juan Muñoz links him to the Spanish Baroque, but he was an international artist throughout his entire career," he says.

“And, furthermore, you have to keep in mind that he died a few days before the 9/11 attacks, which marked the beginning of a time in which we began to stop distinguishing between fact and fiction.

Then the war in Iraq was triggered by weapons of mass destruction that did not exist.

The era of

fake news began.

And the social networks arrived and, with them, the

influencers

, who live a constant representation of his life.

Well, Muñoz had already warned us about all this, who questioned whether he was going to bring us anything good ”.

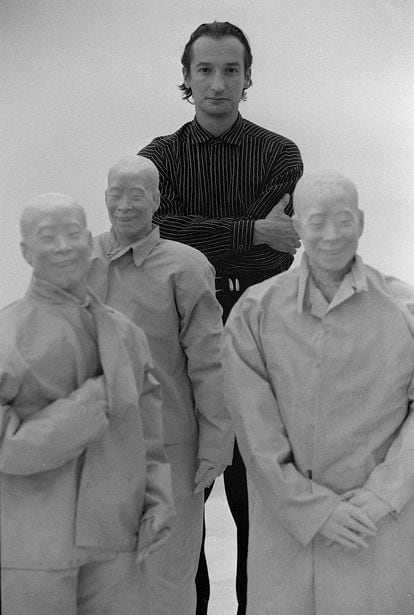

Juan Muñoz, in his first retrospective exhibition, at the Palacio de Velázquez del Retiro in Madrid, in 1996 Luis Magán

His death, due to an aortic aneurysm during a family vacation in Ibiza, at the age of 48, caught him in the middle of his professional qualitative leap.

Only two months before, he had inaugurated Double Bind

at the Tate Modern in London

, a huge installation that today is considered his masterpiece.

And he was preparing his great mid-career solo show at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, which would later travel to other American museums.

Also, according to the curator Vicente Todolí, who is currently working on a catalog raisonné for Muñoz, he was considering new life and professional perspectives: “He wanted to conquer his freedom, abandon the work commissioned by others to do what he called

self-commissions

, self-orders, and be your own patron”.

Todolí, who the following year would become director of the Tate Modern, had developed an intense personal and professional relationship with Muñoz.

He tells that part of the artist's plans included acquiring a ratchet (a Valencian ball fronton) to turn it into a studio and explore new artistic fields.

“Two weeks before his death, I visited him in Ibiza and we talked about his projects.

He told me that, after finishing a phase with

Double Bind

, he wanted to start making works that are less objectual, more performative.

That's where the shots went."

Ship of the Sorigué Foundation that houses 'Double Bind'.

The Estate of Juan Muñoz y Sorigué

It was precisely the return to the object, after the conceptualist tendencies that defended the dematerialization of art since the sixties, that the most radical critics had reproached him with.

His commitment to a figurative sculpture, with some recurring archetypes —the magician, the theatrical prompter, the foreigner, the mountebank, the dwarf—, almost always with gray tones (he was colorblind), which he integrated into theatrical settings, on floors with optical patterns , or in furniture and balconies, garnered as much admiration as suspicion.

Jordi Colomer, also an artist, with whom he had a close relationship in the mid-nineties, warns: “Some critics used the word 'scenography' contemptuously with him.

He felt that his work was treated unfairly in Spain, when he had opened up a new territory for sculpture”.

And not only.

Some of his best works were theater and radio pieces, such as those he did with collaborators such as the writer John Berger, the actor John Malkovich or the musicians Gavin Bryars and Alberto Iglesias (his brother-in-law), where he was able to develop his character as an artist as a combination narrator and magician.

A role that he adopted in public and that gave him part of that legendary aura that already surrounded him in life.

The collector Juan Várez and her husband, Jan Taminiau, together with Sara with Blue Dress (1996), a sculpture from their private collection. Sofía Moro

Knives or playing cards aside, those who knew him highlight his magnetism.

“He didn't like the social life of the art world and, nevertheless, he did it very well”, affirms Manuel Segade.

“Today he is remembered as a kind of Madrid pimp, although he was an intellectual willing to sit down and talk to people, he did not

perform

of a great artist like others of the time, like Anselm Kiefer”.

The Madrid collector Juan Várez, who had come across one of Muñoz's sculptures for the first time in 1997 during a visit to other private collectors in Miami, months later sat next to him at a dinner in Madrid: “I will remember him all the time. life, because it was wonderful.

Very lively and highly educated, he mixed references from the past and the present;

it was evident that he had read a lot, he related everything and made you part of it”.

Várez would end up acquiring

Sara with Blue Dress

, the same piece that he had discovered in Miami, and since then he has only moved it from the hall of his apartment in Madrid to lend it to exhibitions such as the one at Alcalá 31.

The art curator Carmen Giménez, who directed the Picasso Museum in Malaga and was the promoter of projects such as the Reina Sofía Museum and the Guggenheim in Bilbao, worked with Muñoz in 1982 on a mythical exhibition,

Correspondences

, which brought together works by five artists in Madrid and five international architects, from Gehry to Merz, from Chillida to Venturi.

"Juan was very enthusiastic and full of energy," she recalls.

“He was very good at everything: when he spoke, when he wrote and also as a

curator.

But I always saw him first and foremost as an artist”.

Juan Muñoz and John Berger rehearse the radio play 'Will it Be a Likeness?', which aired on the BBC in 1996. Wonge Bergmann (Juan Muñoz Estate)

It took him a while to decide.

Commissioner was just one of the vocations that Muñoz had explored.

Art had interested him since he was a child, when he received private classes from Santiago Amón, his Latin teacher, as well as a critic for EL PAÍS.

But in 1970 he began studying Architecture at the University of Madrid, a career that he ended up abandoning.

He later thought of becoming a filmmaker, but a short documentary on public sculpture was his only achievement in this field.

He also published several critical texts on art.

In 1976 he received a scholarship to study at the Central School of Art and Design in London, from where he went on to the Croydon School of Art. There he met another artist, Cristina Iglesias, who would later be his wife and with whom he had his two children, Lucía (who today runs The Estate of Juan Muñoz, his father's legacy) and Diego.

“We were very young and we hit it off right away, because he seemed different to me, very intelligent and brave.

We grew up together and we shared many things”, recalls Iglesias in the house that they would later share in Torrelodones.

“He always said that in his family he was a weirdo.

He had a lot of personality.

Immediately he wanted to go abroad, as an escape from the mediocrity that he found in the so closed Spain of that time.

He realized that his interlocutors had to be elsewhere, even if he took with him the memory of artists like Velázquez or Goya.

Because at the same time his character was temperamental and very Spanish, very Cheli ”.

'Two sentinels on optical floor' (1990). Meana-Larrucea Collection

Perhaps it was that explosive combination between who he was and how he showed himself that helped open so many doors for him inside and outside our country.

So many and so quickly.

For any contemporary Spanish artist, a career that would take him from his first solo show in 1984 —for Fernando Vijande's gallery in Madrid, a failure: he recounted that because of those first metal pieces he had been called a “scrap dealer”— to, only three years later, another at the CAPC in Bordeaux, then considered the most advanced contemporary art museum in Europe, and in 1990 he became part of the staff of the powerful New York gallery owner Marian Goodman.

In Europe, his supporter was another stellar gallery owner, the German Konrad Fischer.

Even before that, in 1981, during his stay in New York on a Fulbright scholarship,

Muñoz developed a meticulous model for the 'Double Bind' project (2001), which occupied the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern in London.Hugo Glendinning (Juan Muñoz Estate)

Upon returning from the United States, in 1982, it was when Muñoz and Iglesias acquired what was then a small single-family summer home in Torrelodones that belonged to his parents.

During the following years they would expand it to convert it into a studio and home, where their international friends visited them.

“When they didn't see us for a while, in Madrid they thought we had gone to New York, but in reality we were in Torrelodones,” says Cristina Iglesias, smiling.

1996 was the year of his most ambitious exhibitions,

Juan Muñoz: Monólogos y diálogos

, at the Palacio de Velázquez in Madrid, and A Place Called Abroad, at the Dia Center for the Arts in New York, which would later travel to the SITE in Santa Faith. He had carte blanche there to expand his staging, which allowed him to develop more complex narratives.

Until the turn of the millennium came the commission to occupy the immense Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern, for which he was the second selected artist after Louise Bourgeois.

Juan Muñoz, Carmen Alborch and Vicente Todolí, in the nineties.Juan Muñoz Estate

Realizing what the opportunity entailed, he moved to London and worked frantically for months.

Vicente Todolí, who was not yet the director of the Tate, followed the process very closely: “I saw how he put all the meat on the spit.

The result brought together all his obsessions: it was his Sistine Chapel”.

A setting with two vertical levels traversed by disturbing elevators, holes that are sometimes real and sometimes trompe l'oeil, characters that inhabit the space with a halo of alienation.

The interpretations are open to the viewer: existential anguish, the suggestion of mental illness or the Dantesque concept of heaven, purgatory and hell.

When Muñoz died that August of 2001, the work was still at the Tate.

After spending 14 years in storage, Todolí took it to the Pirelli HangarBicocca center in Milan,

of which he was artistic director.

And in 2017 he settled in Lleida, in a warehouse belonging to the PLANTA artistic project, of the Sorigué Foundation, where it can be visited until 2027.

This icon will not be in Alcalá 31 or in CA2M, but many of the themes that

Double Bind

focuses on are developed in both exhibitions.

For Manuel Segade, they reflect aspects such as the terror that lurks behind the domestic and the everyday, which more recent authors such as Mark Fisher have taken up and which many people have experienced during the forced confinement due to covid-19.

Juan Muñoz's legacy is still valid, corroborates his daughter Lucía Muñoz: “Today it is important to remember that Juan touched on fundamental truths.

Because what he was talking about is the human condition.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/HXTIXWY4CZBOVEEG4LB5KEE354.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/7RJED5F3OBGYVEQ5LCBW7OYNMQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/OMA4UFCHWBCAJBF6ZSPZWE4ARQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/IHUP3IGJHBBZZP6JUWU7TVCD5E.jpg)