Every war needs its warp of justifications, a hemp of knotted grievances. All sides demand justice, and it is true that recent or remote history provides a wide assortment of abuses and aggressions that are still raw. But, in a radical paradox, armed conflicts are constructed as collective punishment, an essentially unjust condemnation, the seed of new resentments. Violence will sweep away people who have no guilt or control over the causes of the confrontation. This is not collateral damage, but a perverse strategy that will fuel future wars.

This vengeful hatred creates machines of destruction destined for the future, a delayed horror. Photojournalist Gervasio Sánchez has documented for decades the devastation of anti-personnel mines in Cambodia, Afghanistan, Colombia, Bosnia and Mozambique, some of the most affected areas. Statistics reveal that their explosions hit civilians in 90 per cent of cases. These weapons are designed to inflict serious wounds without actually killing, a feature that, according to Amnesty International, some manufacturers still highlight today in their advertising catalogues: "It is better to maim the enemy than to kill him, since an invalid person entails a much more damaging economic, social and moral cost than that of a dead person".

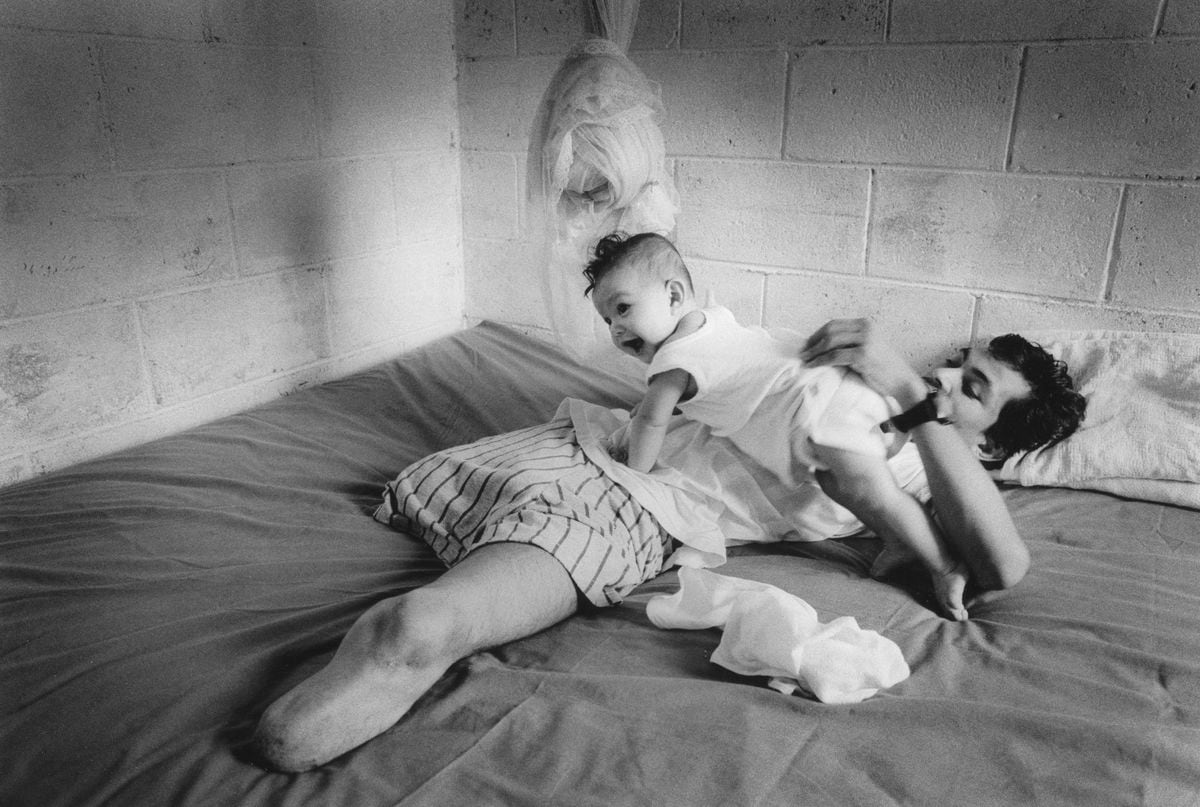

On the 25th anniversary of the Ottawa Treaty, which prohibited the production, storage and placement of mines, Gervasio Sánchez publishes Vidas minadas, where he turns his gaze to those who are the body of memory, the skin of memory, the suffering stump of war. He peeks with the utmost delicacy into their faces and their accomplishments, not just the emptiness of the snatched flesh. It offers light and homage to those who suffer, and has the moral elegance to portray them beyond their condition as victims. The gallery of this book parades children who triggered the explosion while playing or by holding on to a tree branch to urinate on the side of the trail. On the way to the market or school. Young people in the fields, harvesting coffee, planting beans or looking for firewood. This cruel ammunition, designed so that the wound of combat does not heal, so that fear does not become unaccustomed, prolongs a perpetual war that invades peace and mutilates the future. The impossibility of relief. They are cheap weapons, the small change of combat, but no one invests in defusing them afterwards – bombs thrown into the future, perennial snipers, always on the prowl. Called "anti-personnel mines" with a squeaky expression, they inflict their wounds on the most vulnerable beings: refugees, migrants, peasants, children. In the post-war period, people return to abandoned homes. Their land and roads are mined, but they need to work. They can only survive surrounded by the invisible enemy. They have to put their lives on the line to earn it.

Already in ancient times, the classical heroes practiced cruelty towards the innocent with care. In Euripides' The Trojan Women, Odysseus throws a baby from the top of the wall, while Ajax brutally rapes Cassandra in the temple of Athena. Democratic Athens, too, so proud of its civic achievements, exercised barbarism against the conquered cities. Thucydides narrates the assault on Melos, where the Athenians executed all adult men and sold women and children into slavery. The Roman philosopher Seneca, centuries later, would write in his Epistles to Lucilius: "We punish individual murders, but what can we say of wars and the glorious crime of razing entire peoples? We praise acts that would be punishable by death because they are committed by those who wear the insignia of a general. Human beings, the sweetest of animals, are not ashamed to wage war and to entrust their children to make it." This vengeful spiral towards the humblest continues to cut short daily lives. Anti-personnel mines, bombings and kidnappings, sieges, chemical weapons and other forms of latent death still prolong the terrible war paradox of indiscriminate crimes.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Read more

I'm already a subscriber

_