Mexico has put the brakes on the far-right even before the elections are held. Following in the footsteps of the northern neighbors who voted for Trump or the success of Bolsonaro in Brazil and the more recent success of Milei in Argentina, an anti-abortion and pro-traditional family candidate, Eduardo Verástegui, has tried to run as an independent for the presidential elections in June of this year. But it has not obtained enough signatures imposed by the country's tortuous electoral bureaucracy. In Mexico, the far right is hitting a powerful wall of ice for historical and current reasons: the political stability built over the years by the perfect dictatorship of the PRI does not leave much room for adventures on the margins; The country is also currently experiencing an economic solidity that conjures up great social revolts, generous fishing grounds for radical initiatives.

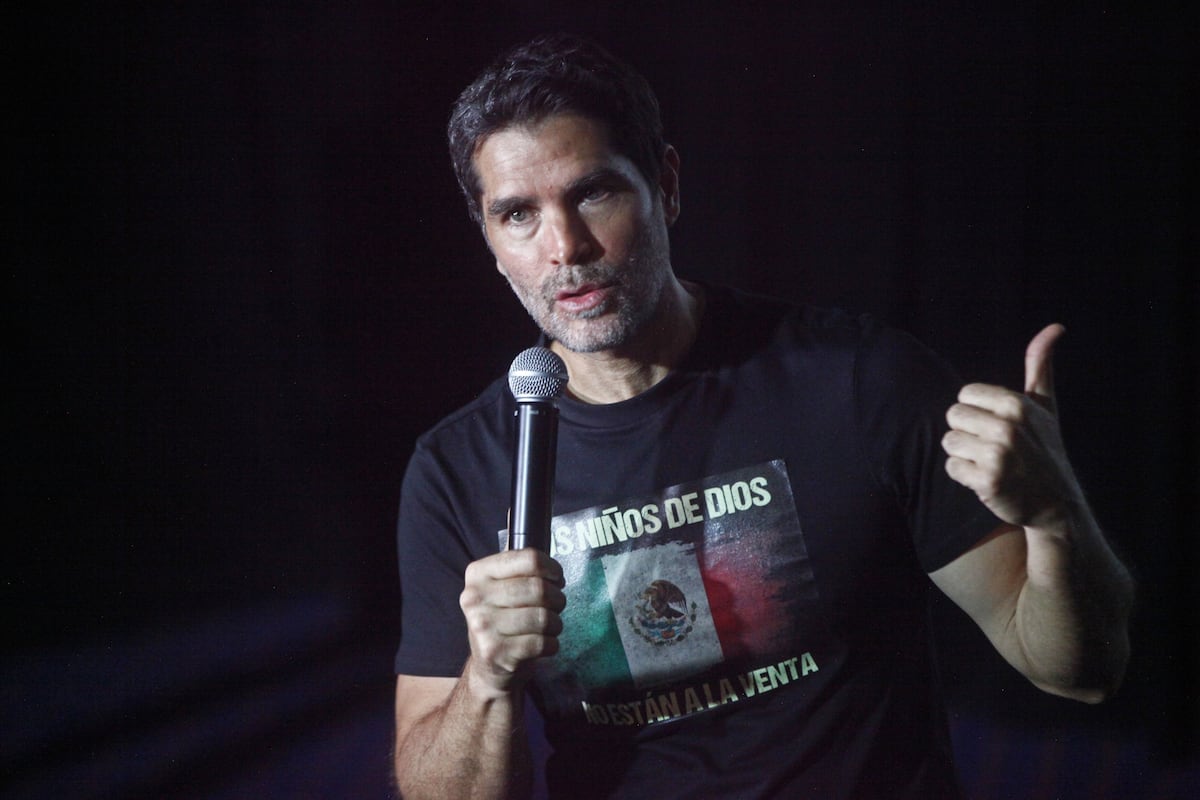

Social networks and their contagious proclamations bring the population closer to any crazy idea that crosses their path, but in Mexico they do not reach the seat that the far right is looking for because there are several reasons that play against it. These days, the main limit is the electoral system, which obliges an independent candidate to collect signatures equivalent to 1% of the citizens with the right to vote, which means about one million, which also has to be distributed equally among 17 states, a major challenge for a candidate without party infrastructure. Forming a party is even more cumbersome and can only be done the year after the elections. So Eduardo Verástegui, a handsome soap opera actor turned politician, barely gathered 14% of the expected support and will have to wait for better luck.

The question, however, remains pertinent: why doesn't the far right catch on in Mexico as is happening in half the world? This North American country has always played against the tide of the politics of its environment. When dictatorships emanating from coups d'état or hopeful revolutions triumphed in Latin America, Mexicans swam anesthetized in the warm magma of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which did not allow for other adventures. Everyone had room in the PRI: "Here the revolution was of the left and the right, under an institutional monopoly. Those who wanted to impose a more radical version of one sign or another were isolated or eliminated," says Mario Santiago, a researcher at the Mora Institute. "The sectors of the extreme right associated with militant Catholicism with the help of some businessmen found a political expression in the PAN of the 1980s," he says. And there are still many of them, in the National Action Party (PAN), the only one that stood up to the PRI for decades without achieving power until the turn of the century, with Vicente Fox at the head.

In September 2021, a political earthquake shook Mexico when several PAN senators received the leader of the Spanish far-right, Santiago Abascal, and a handful of Vox deputies. In historical terms, Mexican independence is still very young and the presence of a leader who likes to recreate himself with the conquest of New Spain and disguise himself as Hernán Cortés raised a dust from which the more moderate PAN senators soon distanced themselves. No one could believe it. Far-right in Mexico? But there were those who believed, like Verástegui, that the PAN is lukewarm with its aspirations, marked above all by stale Catholic postulates.

Vox leader Santiago Abascal with PAN senators in September 2021.PAN SENATORS

A year later, Mexico hosted the world's far-right, in a congress organized by Verástegui in which Steve Bannon, Eduardo Bolsonaro, Javier Milei and the Chilean José Antonio Kast, among many others from both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, participated, live or by videoconference. The far right was emboldened and Verástegui announced his leap into politics with an assault rifle resting on his shoulder and a threat: "Look what we are going to do to the terrorists of the 2030 agenda, of climate change and gender ideology." In the country of weapons, the issue caused a great stir, but it did not get any worse, Mexico continued on its way.

In 2018, after decades of PRI and PAN, a new party conquered power, Morena, led by the current president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, with an incontestable majority that he maintains today and that predicts, according to the polls, a new comfortable victory in June for his successor, Claudia Sheinbaum. The right is trying to take advantage of some of its unfulfilled promises, such as the elimination of insecurity in the country, with an average of 100 violent deaths a day. But that is not the issue that most worries the population, as much as they are fed up with it. The Republic is experiencing days of rosy economics, according to international organizations, with a strong currency, solid investments and exports, minimum wages for the first time above inflation and a promising future that lies in the relocation of companies. It is easy for the president to call the politics of the Argentine Milei "hypocritical."

"The country is polarized in two camps, on the one hand, Morena, and on the other, the opposition bloc, with the PAN as the main party, because its allies in the PRI and PRD are in full decline. If the far right wants to do something, it will have to ally itself with the PAN, where there are already many, but they don't say it openly so as not to frighten the population," says María Eugenia Valdés Vega, an expert in Political Processes at the Autonomous Metropolitan University. "Mexico continues to be a country with liberal traditions and aspirations against inequality that do not allow the far right to express itself as it wants or can in other countries," he says. Vega Valdés also believes that the electoral system is so labyrinthine for the formation of parties and the presentation of independent candidacies that it borders on the ridiculous, which is why "the far right does not have it easy either."

In other areas, Mexico is still in the process of socially conquering rights already consolidated in older democracies, such as abortion, gay marriages or secularism, even though the country successfully dissociated itself from the powerful Church that the Spaniards bequeathed in the viceroyalty. So the strongly Catholic banner brandished by Verástegui's people does not find a place among the citizenry, with a feminism at its best.

In 1953 the national organization of El Yunque was founded in Mexico, where the most Catholic and extreme right is still grouped today, with some universities under its aegis and PAN congressmen related to it. The links of this group with the Spanish far-right Vox are remarkable, even greater than the muscle it shows in its own country. "The extreme right, disappointed by previous PAN administrations that did not attend to its agenda, has taken refuge in the cradle in which it was born, that is, pro-life, family or anti-abortion organizations, in some states of Mexico. They had a strong growth around 2012, but they have retreated to the old spaces," says Mario Santiago, a good connoisseur of this political faction. "To the Catholic agenda of El Yunque, the businessmen breathe a neoliberal economic ideology," he adds, but the businessmen are now very quiet due to the economic future of the country. "The ideology of the Mexican ultra-right is associated more with the Spanish Falangism than with fascism, with a strong statist presence, which is why it sounds so anachronistic, so Cold War, still against long hair among men, homosexuality and in favor of the classic family nucleus," says Santiago. "I don't want to be a futurologist or a catastrophist, but I think that the rest of the monsters, like Trump or Bolsonaro or Milei, are children of economic crises, something that doesn't happen today in Mexico. But you have to pay attention," he suggests.

In any case, the far-right sandwich in which Mexico is stuck in the north and south does not manage to penetrate its borders, even though Verástegui saw hope in that congress in which he was encouraged by the most high-sounding voices on the planet to make the leap to politics. For now.

Eduardo Verástegui in a promotional video for his campaign, in October 2023.EVerastegui

Subscribe hereto the EL PAÍS Mexico newsletter and receive all the key information on current affairs in this country