Issa and Bashir were caught by the outbreak of war while playing in the dirt streets of their village in the Sudanese region of Darfur.

In the midst of all that violence, the two children grew older without caring too much that their tribes were at odds.

They never stopped supporting each other.

Both went to Khartoum, the country's capital, to study at the university.

Issa did not do badly and today he does his small business in the Arab market of this city;

for Bashir things got complicated and he decided to leave.

After a tough two-year journey that took him through Chad, Libya, Algeria and Morocco, on June 24 he jumped the Melilla fence and cheated death.

Dozens of Sudanese lost their lives in the attempt.

This is the story of two friends whom neither war nor distance managed to separate.

More information

Beni Mellal, the exile of those who try to reach Spain

Under the arcades of the old market in Khartoum, Issa Alhadi Mohamed, 31, sips a cup of tea and waits.

Dressed in jeans and a plaid shirt, his business is changing money.

“A client calls me and tells me, I need 100 dollars (97.7 euros).

I give them to you.

Or he wants pounds and I get them for him too,” he says with his everlasting smile.

He has a degree in History, but in this Sudan in deep crisis he earns much more on the black market than teaching, even at the university.

Still, things aren't going too bad for him.

Next year he marries his cousin, who came from the town to the capital to study Nursing: "Four or five children, that's the idea."

Suddenly, a convoy made up of three trucks full of policemen speeds down the nearby avenue.

The agents hit the sides with their batons and howl to instill fear.

Today is the day of demonstration, one more, which ends with another young man shot dead.

Since last October 25 the military entrenched themselves in power with a coup d'état, more than one hundred kids have been murdered at the hands of law enforcement for asking for democracy in the streets.

Even snipers shoot at them from rooftops.

The Sudanese revolution that toppled dictator Omar al Bashir in 2019 is still alive, but hope is fading fast in a country in the process of demolition: armed groups are flourishing inside and threatening new conflicts, inflation is rampant and Sudanese are surviving Hardly.

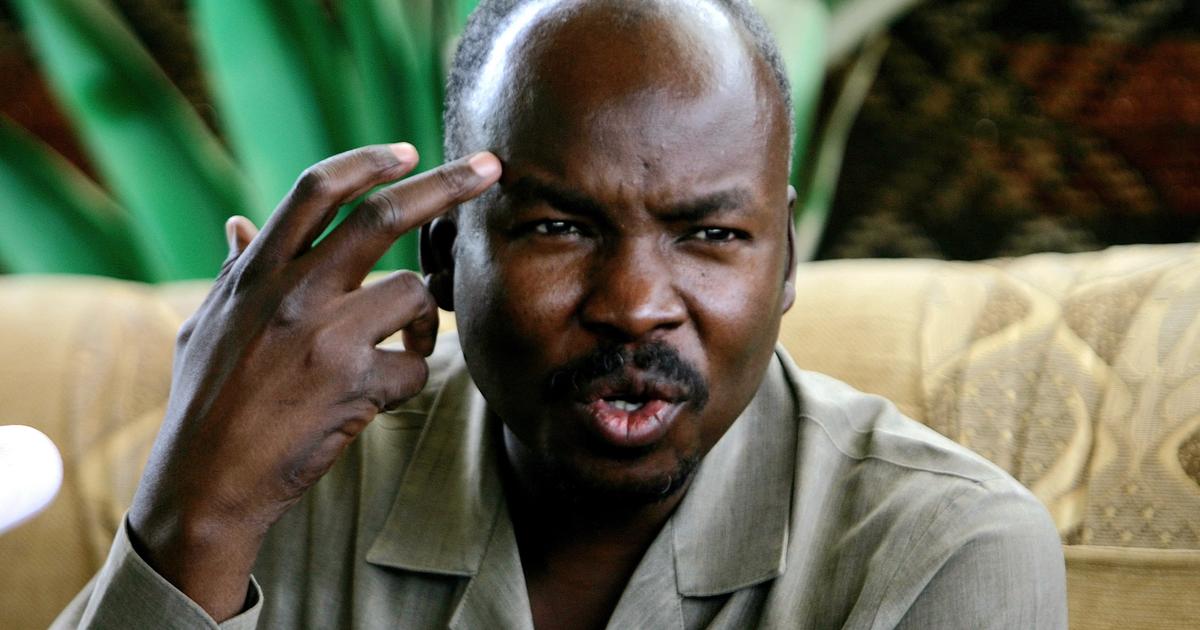

Issa Alhadi Mohamed and Bashir Hamid, in Khartoum in 2020.

“It is not so easy to change a system that has been in operation for so many years,” says Bashir Hamid Mohamed in Melilla.

“To this day, everything remains the same and I hope that it will be others who achieve the change.

I left to find another life.”

Bashir is freshly showered and has a new haircut.

He is a tall and big man, but with delicate movements, sometimes timid.

He doesn't know his exact age, but he estimates it to be between 28 and 30. The three-hour interview takes place on a terrace in the middle of a heat wave.

He sweats non-stop, but he doesn't even drink water.

He is in a hurry to leave Melilla.

The Temporary Stay Center is a limbo for those who long to start from scratch again.

“I would like to go to a nice place.

I have spent months in forests and mountains, and it is true that it is a million times better than prison, with all the fear and torture, but I do not want to stay here, ”he explains.

It will take him a few months to get him referred, as an asylum seeker, to the Peninsula.

During his university years in Khartoum, Bashir got involved in politics and opposed the dictatorship.

In 2013, he was detained for a month for it.

The secret services seized him on campus, blindfolded him and locked him up.

There was no trial or lawyers.

They threatened him.

Already then he began to cultivate the idea of leaving, but he had no money.

He worked selling gasoline in bottles and endured what he could until he decided in 2020.

"When Bashir told me that he was going to Europe, I told him:" Go ahead, look for your luck, away from here you will have more opportunities, "explains Issa, who has been supporting his friend's family financially throughout his trip. .

By then, revolution had broken out in Sudan.

The conflict revives

Today, all that illusion is about to vanish.

Tension between communities and disputes over land have skyrocketed.

Only so far this year there have already been 275 deaths and 117,000 new internally displaced persons.

In 12 of the 18 States of Sudan there are violent incidents, some of them very bloody, such as the old conflict in Darfur, which has been revived fueled by the discovery of gold deposits and the rise to power of the same armed groups that sowed the terror in 2004.

Meanwhile, the capital lives under the routine of demonstrations, daily power cuts and the stagnation of a political process in the shadow of a military regime that controls everything.

"We have lost even hope, but we have nothing more to lose," says the young student Idris Abderramán.

Bashir left Sudan on July 30, 2020. He collected 160 euros and contacted a trafficker who took him first to Chad and then to Libya.

Professor Ikhlas Nouh Osman, head of the Department of Migration at Ahfad University in Khartoum, explains how the exodus of Sudanese, first to Libya and now to Morocco, is a daily phenomenon: "It is normal for thousands of Darfuris, Libya has It has always been a migratory destination for them, but living conditions have worsened a lot in that country after the political crisis generated by the fall of Gaddafi.

It is very hard, migrants in Libya suffer mistreatment, kidnapping, extortion, labor exploitation... They cannot return to Sudan empty-handed and at the same time they are suffering a lot in Libya.

It is normal for them to look for new routes”.

Bashir does not want to relive his time in Libya, but he does share some memories.

“I know people who died.

I've lost a lot of friends there, I can't get over that.

No one is safe.

I myself spent time in Abu Salim prison after I was caught by the coast guard,” he says.

In the end he paid 1,450 euros to a smuggler to cross to Algeria and two weeks later he managed to arrive in Oujda after jumping the fence that separates Algeria from Morocco.

And last September he arrived in Nador.

After almost twenty failed attempts, arrests, transfers to cities in the south and enormous frustration, on June 24 he finally achieved his goal.

He crossed the Melilla fence in the deadliest episode of the Spanish land borders.

The Moroccan Association for Human Rights (AMDH) raises the number of dead to 27 (and not the 23 recognized by the Moroccan authorities).

Another 64 are missing.

The vast majority are Sudanese.

A woman walks in the Al-Geneina IDP settlement, West Darfur, one of 100 camps in the region.Dalila Mahdawi (Dalila Mahdawi/MSF)

The tragic news circulated through the networks in Sudan, jumped from mobile to mobile, from home to home.

Fatima Saleh, a young Darfuri, reflects on the disappearance of so many young people who leave: “These boys leave and many times their trail is lost in the desert, in Libya or in the sea.

You will never have an official confirmation that your son or your brother has died.

Only their shadows remain.

One day, the phone stops ringing or the messages are interrupted.

As if they had been swallowed by the land or the ocean.

Literally.

In my region all families have someone who has left, my own cousin died in emigration a month ago.

If he was one of those who jumped the fence?

How to know?

We had the luck of a call, many families not even that”.

In the Sudanese capital, Issa is happy.

He wanders between the mobile phone and Saudi jewelery shops of the Al-Waha mall as if he owns everything.

He talks every day with his friend Bashir.

They greet each other and tell each other news.

"Throughout his trip we were talking, he told me where he was going and I sent him strength from here, we did it through Facebook," he explains.

“Can he work now?” he asks suddenly, “maybe now he'll be the one to help me”.

Issa remembers when Bashir's family was in serious financial trouble and he paid her high school tuition.

"I will never forget what he did, since then I knew that our friendship would last forever," explains Bashir in Melilla.

"Despite tribal differences, we are together and will be friends forever."

For decades, the Arab countries of the Gulf, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt were a preferred destination for the Sudanese diaspora.

They shared culture, religion and language.

It was above all an emigration of professionals, architects, doctors, engineers, who found better living conditions in these rich countries.

In times of the dictatorship of Omar al Bashir, even Sudanese companies settled there to survive international sanctions.

However, the deep crisis in Sudan has also pushed uneducated young people abroad and the Gulf countries have begun to put restrictions on their poor neighbors in Sudan.

With the Arab world increasingly hostile and Libya tightening control mechanisms at the behest of Europe,

Social anthropologist Munzoul Assal of the University of Khartoum warns: “This is just the beginning.

It is obvious that they will leave younger and younger.

The situation is bad, terrible and at the same time volatile.

Nobody knows what will happen, it is even possible that a civil war will break out.

And today we have social networks, kids with an uncertain future see that on the other side there is freedom, a better life”.

The Government hardly recognizes the migratory phenomenon, it continues to consider Sudan a transit country for Eritreans or Ethiopians, and there are no policies regarding mobility aimed at nationals.

A frustrated revolution

On April 11, 2019, the world turned its head towards Sudan with a gesture of unequivocal joy.

After months of demonstrations, which began with the rise in the price of bread, and dozens of deaths, the army staged a coup and overthrew the dictator Omar al Bashir, who had been in power for a whopping 30 years and was persecuted by the international justice.

The Sudanese revolution had triumphed.

Or so it seemed.

After months of tough negotiations, a government led by the civilian Abdullah Hamdok, but still protected by a council chaired by the military, took charge of the country and embarked on a path of profound reforms.

A moment of the demonstration on the 26th in the streets of Khartoum against the military coup.

Marwan Ali (AP)

Fath Abdurramán Mohamed, a member of a popular resistance committee, remembers that time: "It was a difficult two years and we had to tighten our belts, but we all shared the dream of a new Sudan."

However, on October 25, 2021, everything fell apart.

General Al Burhan, at the head of the military junta, dismissed Hamdok and his government, whose reforms were beginning to affect the Islamist-military elite that had ruled the country in the last three decades.

The alleys of the neighborhoods of Khartoum became tributaries of young people who once again flowed into the great avenues of the city center.

International organizations, such as the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund, once again withdrew their aid.

Bilateral cooperation with the United States or the European Union was blocked again.

Still under the impact of the trade disruptions of covid-19, the Ukraine war came in February.

Prices, which were already high, have skyrocketed to unbearable levels and Sudan has reached an annual inflation rate of close to 400%.

“Filling my car's gas tank literally takes a third of my monthly salary;

Buying food today in this country is juggling,” says merchant Idrisa Mahmoud.

One in four Sudanese is already in a situation of food insecurity, the highest figure in the last decade, according to the United Nations.

Neither the military have managed to gain full control of the situation, with outbreaks of violence in different parts of the country, nor does civil society seem to have enough critical mass to knock them down.

Atta Albatahani, Professor of Political Science, concludes: “Inter-community conflicts have re-emerged and the leaders of the former Islamist-military regime continue to pull the strings of the economic sectors for their own benefit.

Two thirds of the population is under 24 years old and these young people, fascinated by Europe, by Real Madrid and Barcelona, lead another life by power, they are trapped between a divided civil society and a regime that does not listen”.

50% off

Subscribe to continue reading

read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/WPWGX6DIRZA3DAQ7GEHRNPNOLQ.jpg)