All trauma usually takes years to become art.

But the attacks on January 7-9, 2015 in France, whose trial began on September 2 and is due to end in mid-November, have already led to an abundant bibliography.

A chapter in the success of

this year's literary

rentrée

,

Yoga

by Emmanuel Carrère, deals with the attack on the satirical magazine

Charlie Hebdo

.

It is the most recent example.

In the last five years, there have been essays, comics, and more or less literary stories that would be enough to fill a shelf.

Also account adjustments.

Here a selection.

Director.

Laurent Sourrisseau, or Riss, who was wounded during the

Charlie Hebdo

newsroom

shooting,

doesn't want to be called a victim.

He said this when testifying a few days ago at the trial for the January 2015 attacks, and he explains it in

Une minute quarante-neuf secondes'

(Actes Sud, 2019, in French).

"Victim is a word that places one next to the dogs beaten by their masters, the children who are victims of their parents, the dismissed for economic reasons who are victims of the laws of the market," he writes.

Innocent: I was innocent.

Victim, no ”.

The book deconstructs in slow motion the minute and forty-nine seconds that the shooting lasted.

But it is more than that.

These are memoirs in which Riss explains his relationship, since childhood, with death and violence, and a series of profiles of his dead companions.

It also includes a charge against what he calls the "collaborationist spirit" of those who accused the satirical weekly of Islamophobic or racist for caricaturing Muhammad, against "that totalitarian left [that] adapted, according to the times, to Stalinism, Maoism, to the Khmer Rouge, to the Iranian Islamic revolution and today to Islamism ”.

The writer.

On January 7, 2015, he has already left at least one literary work of the first magnitude.

Philippe Lançon, cultural columnist for

Charlie Hebdo,

narrates in

El flagajo '

(Anagrama, 2019, translation by Juan de Sola) the minutes of the attack, in which his face was disfigured, and the months of hospitalization and physical and moral reconstruction.

Lançon achieves a rhetorical and human feat: describing an attack with an almost clinical attention to detail, without pathos, but with the ability to bring the reader as close as possible to — and imagine — what those moments meant to live there.

He did feel like a victim.

"He was a victim of war between [the squares] of the Bastille and the Republic," he says in reference to the geographical location in Paris of the newsroom.

"I was a war wounded in a country at peace, and I felt helpless."

The cartoonist.

Catherine Meurisse was living a heartbreak story with a married man, feeling confused and discouraged, and that day she woke up too late to be on time for her Wednesday morning meeting at

Charlie Hebdo.

That saved her.

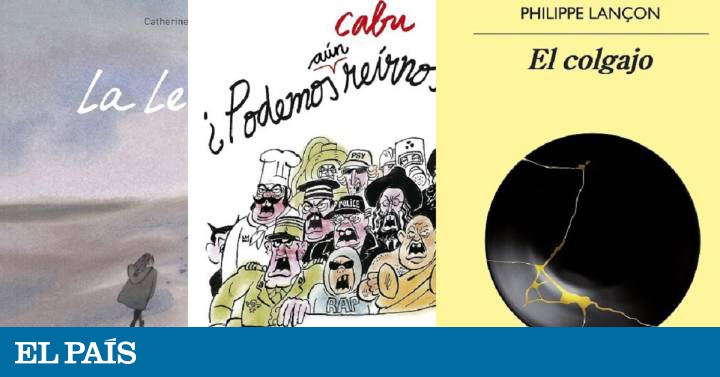

He explains it at the beginning of the comic

La levedad

(Impedimenta, 2017, translation by Lluís Maria Todó), the lyrical and first-person account of a survivor: the irruption of violence and chaos, life under police protection, the reconstruction of the magazine and black humor (always) through thick and thin, visits to the psychiatrist, sadness and finally the trip to Italy and the search for beauty.

“What seemed most precious to me, after January 7, was friendship and culture,” says a friend during a trip to the mountains.

"It's beauty to me," Catherine replies.

"It's the same," she adds.

The kiosk.

Le kiosquier de Charlie

(Equateurs in French, Bompiani / Rizzoli in Italian, 2016), by journalist Anaïs Ginori, tells the story of Patrick, the newsagent in Saint-Germain-des-Près, the most literary quarter of Paris, right in in front of the cafes of Flore and Deux Magots, which existentialists frequented.

At this kiosk, neighborhood cartoonists Wolinski and Cabu bought their copies of

Charlie Hebdo

on the morning of January 7, 2015, before heading to the weekly newsroom meeting.

The newsstand Patrick knew nothing of the attack when, while he was driving back to his house on the other side of Paris, unknown men assaulted him and stole his vehicle.

They were the Kouachi brothers, who had just murdered their clients in

Charlie's

newsroom

and were on the run.

From this story, the correspondent for

La Repubblica

in Paris reconstructs those days.

And, through this story, he reflects on the crisis in journalism and the threats to freedom of expression, which are projected onto a simple newsstand.

"He could have died and survived, at a time when his dying craft, on the verge of extinction, today seems resurrected," Ginori writes, describing

Charlie Hebdo's

temporary sales

boom

after the attack.

"Shit, go to a newsstand, buy 'Charlie' and buy other newspapers, not shit, but something a little smart," exhorted the cartoonist Luz, quoted in the book, a few days later.

"If we can make kiosks live, if we can make paper live, if through these kiosks and this paper ideas can be made alive, all over the world, at least in France, we will have really won."

The conflict.

In the books by Riss and Lançon there are harsh reproaches to those who, by "isolating and despising"

Charlie Hebdo

for publishing the cartoons of Muhammad in 2006, turned him into "the target of the Islamists", as we read in

The Flap.

During the trial, these reproaches have been heard again.

This same week the magazine's cover features cartoons of left-wing journalist Edwy Plenel, left-wing populist leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Islamist essayist Tariq Ramadan suggesting that they sympathize more with the Kouachi brothers than with

Charlie.

Two books published in France at the end of 2015 summarize a clash that also confronts different ideas of what

Charlie

is

and different views of the left (there is a background, in addition, of less high litigation, of a pecuniary nature).

The journalist Denis Robert lashed out in the

Mohicans

(Julliard)

essay

against the team led by

Charlie Hebdo,

founded in the 1970s, since its resurrection in the 1990s.

Robert, from a leftist position and invoking the figure of the founder Cavanna, described the former editor Philippe Val, his successor Riss and the magazine's lawyer, Richard Malka, as a clique that supposedly would have betrayed the values of 'Charlie'.

In the same days, Val published 'C'était Charlie' (Grasset).

"A part of the left willing to liquidate secularism in order not to lose a reserve of votes, insulted us by treating those who expressed their regret and their attachment to the democratic values embodied by the victims of terrorism as zombies," he complained.

So I decided to write this book.

For the memory of the dead and the honor of the living ”.

The classics.

There is no better legacy of the

Charlie Hebdo

dead

than his works.

There is no better way to understand the magazine.

In 2015, after the attacks,

Can we still laugh at everything?

(Peninsula, translation by Eduardo G. Murillo), from Cabu.

The cartoons make fun of everyone: politicians, singers, athletes.

And of religions.

"Fuck all religions," says one of them in which you see rolls of toilet paper that represent the Bible, the Koran and the Torah.

The keyword, of course, is "all".

In another cartoon, entitled "Can we laugh at pedophilia?", A Catholic priest is seen hugging a group of happy children.

Another child who seems excluded from the group cries and says: "It's just me ... sniff ... sniff ... the one that Monsignor does not like."

Cabu and

Charlie

were like that.

Hooligans and irreverent, with a humor often of a broad brush and that could border on bad taste, a humor that was not made to be liked or to flatter the intelligence of the reader but rather to shake it.

Cabu and company did not make illustrations or vignettes for the

New Yorker,

nor did they pretend to.

De Wolinski, another of the classics, was published in French in 2019

Les falaises

(Seuil), an anthology of his drawings of men and women facing cliffs, “a spectral place in which the impossible passage between the two shores that separate life and death, ”wrote her friend, the psychoanalyst Élisabeth Roudinesco, in the prologue.

One of the last vignettes shows a coach with the inscription

Charlie Hebdo

and full of people inside.

The coach jumps off a cliff.

"If we get out of this," says the driver, "it's a miracle."