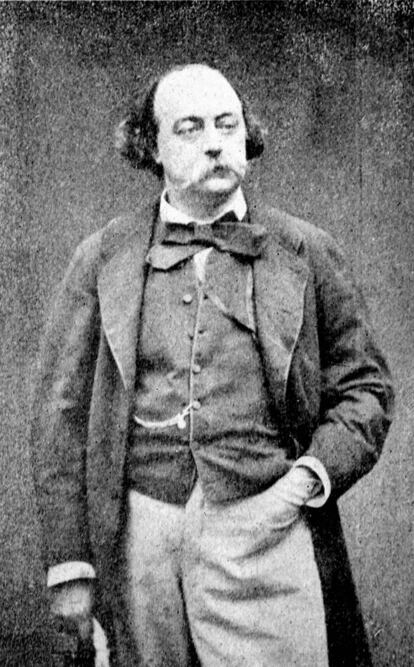

Portrait of Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880), by photographer Nadar.ROGER_VIOLLET

Gustave Flaubert had a relationship with his hometown, Rouen, that ranged between love and hate. Rather the second than the first, judging by the reproaches he dedicated to him in his private correspondence. "It is a place full of beautiful churches and stupid inhabitants," he wrote. "Let lightning destroy Rouen and all the morons who live in it, including me." It is not surprising that, on the 200th anniversary of his birth, which takes place this Sunday, Rouen dedicates a discreet tribute to the most peculiar of prodigal sons. In the city, only a couple of exhibitions remember the father of the modern novel, who did not have a street named after him until the 1950s, seven decades after his death. A third sample, dedicated to his work

Salambó

at the city's Museum of Fine Arts, it ended a few weeks ago.

In the square that surrounds the museum, a statue can be seen in the distance.

It is enough to get closer to discover that it does not pay homage to Flaubert, but to Guy de Maupassant, despite the fact that he was born 60 kilometers from the place, almost in the ocean.

To run into Flaubert, you have to go a little further from the center and enter the house where he was born, in the so-called Hôtel-Dieu, a small mansion attached to the old hospital in Rouen, where his father worked as a chief surgeon.

Today it houses a museum dedicated to his memory, as endearing as it is dusty, full of those relics that led Julian Barnes to write

Flaubert's Parrot:

his first article, his childhood colony, the stuffed bird that would have inspired

A Simple Heart.

(although his other house-museum in Croisset, on the outskirts of the city, claims to have "the real one"). The aura of the place is relative: the room of his childhood is a reconstruction of 1923. Everything is illusory, except the moldings on the wall. But it was within these walls that he spent his first quarter of a century, in a low-ceilinged residence where sickness and death were neighbors. "Only one door separated us from the room where the sick died like flies," he once wrote. In the garden, a neoclassical bas-relief represents the author as a floating head with a mean face; one would say that he would rather be anywhere else. At that time, Flaubert was a child who devoured Shakespeare and Montaigne, not interested in following in the footsteps of his father (the first-born, Achille,freed him from that burden) and that he found in writing, from the age of 9, his only hobby.

Flaubert never wanted to marry. For him, his trade was only compatible with singleness. Only in this way could he write every day until dawn, in his incessant search for 'mot juste', the right word

Flaubert despised Rouen for his bourgeois mentality, which he portrayed with ruthless precision in some of his novels, and dreamed for half his life of fleeing towards the East, which he would end up discovering as an adult, somewhat disappointed not to feel the ecstasy of Chateaubriand in the Holy Land. And, at the same time, the capital of Normandy, lazy and wealthy provincial city where the Haussmann-style palaces continue to hide medieval crossings with exposed wooden beams - as is mandatory in this corner of French geography - was a constant inspiration in his work, for the good and the bad. In fact, Flaubert always felt Norman to the core and even compared himself, without fear of ridicule, to his Viking ancestors. “I am a barbarian, I have his muscular apathy, his nervous languor, his green eyes and his great height,but also his stubbornness and irascibility. Normans as we are, we carry cider in our veins, "he wrote to Louise Colet, the mistress he always refused to marry.

Isabelle Huppert played Madame Bovary in Claude Chabrol's 1991 adaptation of the same title, shot in Normandy.

Faced with the romantic idea of love, the author preferred the

amitié amoureuse

, that invention so French that it avoided jealousy and, above all, commitment.

"The first thing in life is not to love, but to write," he said in another letter, making it clear that his was almost a priesthood.

Contrary to bourgeois conventions, despite coming from that social class, he believed that his job was only compatible with singleness.

Only in this way could he work every day until dawn, in his incessant search for the

mot juste

(the right word), in the family home in Croisset, where he settled after being acquitted of the immorality trial caused by

Madame Bovary.

, which made him a literary star at 35, but also a public enemy. This mansion overlooking the Seine, currently under construction, will house a reconstruction of the studio where he spent 15 years signing his three great novels, five years for each title:

Madame Bovary

,

Salambó

and

La Educación Sentimental

. There he spent hours declaiming his sentences aloud, attentive to any repetition or assonance, and then writing down and rewriting his manuscripts, objects of worship for those who study the genealogy of the text.

In the region, different municipalities dispute the dubious honor of having inspired the landscapes of Flaubert's novels.

For example, three localities have been recognized in Yonville-l'Abbaye, the town “set apart from the plain and situated eight leagues from Rouen” where

Madame Bovary used to pass

.

Among them is Ry, where a young woman named Delphine Delmare committed suicide in 1848 after accumulating unpayable debts and going through various adventures, leaving behind a six-year-old daughter whom she never took care of excessively.

That is, the same thing that happened in the novel.

Presided over by a picturesque street where several shops bear the name of Emma, the protagonist of the book, Ry stands as the capital of a

Flaubertland

that takes all the tourist profit it can from the fame that the author gave him, even if it was bad.

“Man is nothing; the work is everything, ”said Flaubert, foreshadowing the 'death of the author' that Barthes decreed in 1968. Mario Vargas Llosa, Orhan Pamuk and Annie Ernaux swear they owe them everything

In the absence of great tributes, the best reverence for an author who never fell into the category of national writer will continue to be that of his fellow workers, who continue to regard him as something of a commander. Shortly after his death, Proust and Kafka vindicated their style. Faulkner made a pilgrimage to Rouen, while James Joyce was inspired by his free indirect style, that subjective realism where the narrator entered and left the heads of his characters. Sartre dedicated a long biography to him,

The Idiot of the Family

, just as Foucault and Bourdieu devoted essays to him. Claude Simon quoted him when he won the Nobel, confirming the debt that the

nouveau roman

he had with his legacy, with the notion that the main thing was the language and the style, and in no case the author. “Man is nothing; the work is everything ”, said Flaubert, foreshadowing the

death of the author

that Barthes decreed in 1968. Mario Vargas Llosa and Orhan Pamuk admit that they owe them everything. Also Annie Ernaux, a Norman like him. "He was my first teacher, my first model," he confessed a couple of years ago on the couch at home. For Leila Slimani, literary star of the latest batch, Flaubert continues to be "the only one, the true one, the best of all."

There are many false legends surrounding the author. His obsessive writing temperament is not one of them. At the end of

Sentimental Education

in 1869, he sent a letter to the Goncourt brothers: "I sweat blood, I piss boiling water, I defecate catapults, and I burp boulders." Instead, he probably never uttered his most famous phrase - "

Madame Bovary, c'est moi

"

-, which was never heard first-hand and is only documented in an essay from 1908. If he did say it aloud, it may have had another meaning than that which has gone down in history.

"I was a man and a woman at the same time, lover and beloved together," he expressed in a letter to Colet in which he described how he felt when initiating the mythical passage of intercourse in the forest, which earned him the condemnation of censorship.

"I was the horses, the leaves, the wind, the words that were said and the red sun."

It is probable that Flaubert identified more with the work as a whole, which he felt like an organ of his own, like a limb impossible to amputate, than with a character whom, deep down, he treated as a poor deluded man who believed that love was her. was going to save.

He never fell so low.