I have a special fondness for Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite of our planet, for a reason as pilgrim as that it was put into orbit the same day I was born. Yes, I know, it is a stubbornly Ptolemaic vision to put yours at the center, and yet I have always thought that somehow it must mark you to have been born at the same time as that wandering star launched by the Soviets: like Lee Marvin under his. These days it is more fashionable to talk about Oumuamua, the rare comet that crossed our solar system and that astrophysicist Avi Loeb, with an imagination worthy of Appointment with Rama, has considered that it could be the first sign of intelligent life beyond Earth. In fact, Sputnik 1, the junk launched by the USSR on October 4, 1957 and whose name means "traveling companion", remains outdated: old junk of the space race (really, joining your destiny to something like that has its drawbacks, for comparisons). But his ascent to heaven from Kazakhstan just when my mother was fighting for me not to be born at all in the family's Seat 1500 on the way to Barcelona's Adriano Clinic was a landmark moment. "The space age begins", "The man on the threshold of space", "Russia launch man's first moon", "Soviet fires earth satellite into space", are some of the headlines that newspapers around the world dedicated to the event, most of them on the front page and in five columns (Pravda, as it had no competition, did so the next day, although it took the opportunity to teach that "the free and serious work of the people of the new socialist society will make the humanity's boldest dreams").

More information

In space no one hears your screams

Sputnik, launched on an R-7 rocket, shocked the world, especially the United States, who saw swallowing as the USSR with its "red moon" was unexpectedly ahead of them, in what could be a decisive military advantage in the middle of the Cold War. Americans watched him pass through their sky (every 96 minutes) with the natural apprehension of those tense times. It came to be considered as a new Pearl Harbor. Lyndon B. Johnson, then majority leader in the Senate, warned of the Soviets, who had been nuclear power since 1949: "Soon they will drop bombs at us from space just as children throw rocks at cars from a highway bridge." The Russians are coming!, but from above, not in submarine as in the movie.

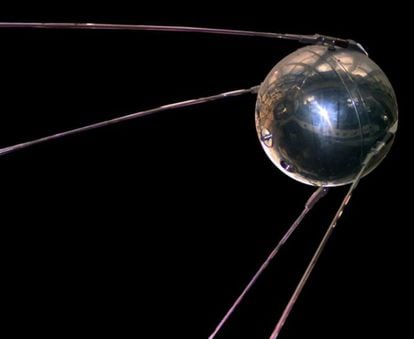

The artifact, as Ricardo Artola recalls in The Space Race (Alianza, 2019), was a burnished aluminum sphere of 84 kilos (in comparison, I weighed three) and 58 centimeters in diameter, with four thin and long antennas and two radio transmitters that emitted sounds regularly: beep-beep-beep. The equivalent of my mother in Sputnik was the "chief designer" (he was always called that) Sergei Korolev, who picked up the tradition, to call it in some way, of Nazi rocketry, in the same way that the United States did with that genius of pragmatism and relocation that was Wernher von Braun, who went from launching rockets over London to Hitler's joy to sending them to the Moon (and putting there, with Apollo 11, the first man, in 1969). But that was later; then, when I and Sputnik were born, Americans were lagging behind. They tried to launch their own first satellite, the Vanguard, tiny, just over a kilo, two months later, but a few meters high, the rocket engine stopped and fell ignominiously. He was sarcastically baptized as Kaputnik. All the triumphs were scored by the Soviets: the first animal in orbit (the dog Laika, in Sputnik 2, a month later), the first human being (Yuri Gagarin, my cosmonaut idol), the first woman (Valentina Tereshkova, who was a paratrooper)... Then came the first crew, the first spacewalk, the first space station, the first unmanned capsule on the lunar surface, the first rover...

The 'Sputnik 1', the first artificial satellite in history.

The Soviets also sent the first black man, the Cuban Arnaldo Tamayo-Méndez, as recalled by the (black) astrophysicist Neil DeGrasse Tyson, considered the successor of Carl Sagan, in his suggestive Chronicles of Space (Paidós, 2016). When I interviewed him a few years ago, Tyson, who has a great sense of humor, pointed out to me that the first mammals in orbit were, in order, "dog, guinea pig, mouse, Russian man, chimpanzee and American man." It also gave me the best possible description of what Venus actually is: if we put a raw pizza on a windowsill on the planet it would bake in 9 seconds (they are there at 480º). By the way, as for extraterrestrial intelligent life, DeGrasse Tyson reflects that our greatest fear is that aliens will treat us as we would. So they enslave us or put us in a zoo.

In short, all this Sputnik —see the seminal Red Moon Rising, by Matthew Brzezinski (Bloomsbury, 2007)— comes to the fact that I have spent a few days off in Formentera and I have taken the opportunity to read Sputnik, my love (Tusquets, 2002), by Haruki Murakami, thinking that Sputnik should come out and who knows maybe even me (in fact there is a phrase in the book that is not even painted: "If you invented a car that ran on stupid jokes, you'd go pretty far.") But the title comes from the sympathetic confusion that Myû has, one of the three main characters (she, the young Sumire, who loves her, and the narrator, K, who loves Sumire) of Sputnik with beatnik, and that leads Sumire to call Myû "Sputnik, my love". Of course, that is not entirely true, that Sputnik is just a mistake, and Murakami actually takes full advantage of the metaphor of the satellite, turned into the authentic leitmotif of the novel, to talk about love, heartbreak (neither the narrator nor Sumire are reciprocated) and loneliness.

The lighthouse of Cap de Barbaria, on the island of Formentera.Rafel Rosselló Comas (Getty)

Formentera was great, very few people (although it will be filled this weekend with the Half Marathon), but everything was already open, the long day and without the summer heat; cold water, that's why. Few news: the Sol y Luna, Migjorn's restaurant with the unmistakable checkered rubber tablecloths, will now be run by the Martí family; a very nice new waiter, Amador, Andalusian, has joined the Colombian family of Pelayo; the Tur Ferrer Bookshop, in Sant Francesc, is renamed Tur Bookshop, but the lovely dog Dolça and her owner are still there; on the roof of the Rafalet bar has been installed a seagull of Audouin that has fried to the waiters because someone is careless takes the bread with things ... Reading on the island Sputnik, my love has been a very special experience, even more so because in the novel there is an unnamed Greek island (closer and Mediterranean obviously than Tokyo) in which the central events of the plot take place, and to which the narrator takes two novels by Joseph Conrad, by the way.

Sputnik... "Sumire loved the resonance of that word (...) The artificial satellite silently piercing through the darkness of space." Explains the young woman: "Sometimes I feel very helpless. The loss of the bond of gravity, the sensation of floating alone through black space, adrift. Without even knowing where you're going." "Like a tiny Sputnik that went astray?" asks his friend, the narrator. "Maybe." And in another passage Myû notes: "Sputnik, fellow traveler, why would the Russians give such a strange name to an artificial satellite? It was nothing but an unhappy piece of metal that went round after lap, completely alone, around the Earth." And later he rounds off the image as a simile of disgruntled love: "We were nothing more than two lonely pieces of metal tracing their own orbit. From afar they looked beautiful as shooting stars. In reality, we were just prisoners without destiny locked each in their own capsule. When the orbits of the two satellites crossed casually, we met. But it only lasted an instant. Moments later we were again immersed in the most absolute solitude. And someday we would burn and be reduced to nothing." The narrator adds: "In people's lives there is a special thing that can only be had in a special time. It's like a small flame. Cautious and hopefully careful people preserve it, make it grow, carry it like a torch that illuminates their lives. But once it's lost, that flame can never be recovered." Sputnik... Images of lives that intersect fleetingly, loves that are born and disappear, satellites that cross space, fall and burn.

Haruki Murakami, photographed in 2011 at the Palau de la Generalitat de Catalunya.

By one of those coincidences that Jung called synchronicity, just as I was writing these lines, another book has fallen into my hands, Retén el beso, by psychoanalyst and essayist Massimo Recalcati (Anagrama, 2023) and with the famous painting El beso, by Francesco Hayez, on the cover (not to be confused with the Kiss Beach of Formentera). They are seven "brief lessons on love" that draw the trajectory (the orbit, we would say) of a love relationship from the beginning to the end and that, in its penultimate chapter, Separations, question precisely if it is better to "last than to burn". That is: "Wouldn't it be better to burn without needlessly pursuing the illusion of lasting?" To last and burn, says Recalcati quoting Barthes, are excluded: if a love burns, it does not last, and if it lasts, it does not burn. Sputnik... To end the lover Sumire: "This love will lead me somewhere. Maybe it will take me to a special world I've never known. To a place full of dangers, perhaps. Where something is hidden that inflicts a deep, deadly wound on me. Maybe I'll lose everything I own. But I can't go back. I can only abandon myself to the current that runs before my eyes. Even if it consumes me in the flames, even if it disappears forever."

After orbiting Earth 1,440 times in 92 days, Sputnik 1 incinerated on re-entry into the atmosphere on January 4, 1958.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Read more

I'm already a subscriber