I had met Milan Kundera at his house in Paris and, as I entered 7 rue Littré where he lived, I stopped in front of the elevator door. From there came a tall, athletic gentleman with white hair. I asked him in French: "Can you tell me which floor Mr. Kundera lives in?", He gave me a funny smile and told me that I had to go up to the penthouse. So I did, and I was opened by a lady who introduced herself in Czech as Vera Kundera and added that her husband had just gone out to buy tobacco. "Let's see if he comes back," I dared to reply laughing, because all Czechs know the anecdote about the writer Jaroslav Hasek, who one day left his house to buy tobacco never to return. But the anecdote did not open Mrs. Vera's heart.

We had not had time to establish a fluent conversation when the sound of the key in the lock was heard and the same white-haired gentleman whom I had asked a few minutes earlier about Milan Kundera entered. The man laughed out loud. Then we went to a Moroccan restaurant near his home, in the Place de Montparnasse.

More information

The author of novels such as 'The Unbearable Lightness of Being' and 'The Joke' was one of the most important storytellers of the twentieth century

That was in the mid-eighties, I was in my twenties and Kundera was approaching sixty. I was then his translator into Catalan and I had a list of doubts to consult the writer who had recently become famous with his novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being. As we dismissed the doubts, the writer stressed again and again how much he cared that all translations were absolutely faithful. "Above all, we must not pretend to interpret my intentions!" he repeated.

While we tasted some pastries in the Moroccan restaurant, we talked about other things that interested us both. We soon agreed that, unlike many refugees, neither he nor I experienced exile as a tragedy, but as luck, as an adventure that never ended. Vera disagreed. Years later, she confessed to me that living abroad was the big mistake of her life.

That meal with the Kunderas was the beginning of a friendship both epistolary, at that time even without internet, and based on meetings during my trips to Paris or the visits of the Kunderas to Barcelona, where their publishing house was and still is and in whose surroundings at that time the couple was looking for a country house as a second residence.

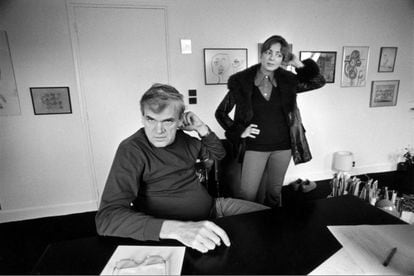

Milan and Vera Kundera in Paris.Gyula ZARAND (Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

The fact that the three of us lived in Prague and then abroad was always an experience that united us and our conversation often revolved around it. In fact, for any exile, his experiences outside his country are the most profound thing he has experienced and becomes the subject that dominates both the conversations and the theme of the books if it is a writer. From his immigration, Kundera investigated this issue in several of his novels.

We also talked about the Prague we had left behind. Kundera told me that this feeling of being a foreigner and not understanding anything about the host country tortured him for a long time. What traumatized him most was not knowing French well enough. This, for a writer, was tragic, he said, even if he accompanied that statement with a smile.

While we taste the main courses, couscous and tagine, we continue talking about Prague, that city par excellence of Kundera. I realized that Milan was Prague. Although after his Parisian exile he has written about other cities, in his work Prague is a city much more flesh and blood than the others. Its Prague is the streets through which Franz Kafka and Jaroslav Hasek walked, where Czech, German and Yiddish were spoken and written, where several cultures and millenary traditions were amalgamated: a Central European city par excellence, which ended under the boots of the Nazis. Kundera's literary models were, in equal measure, Kafka and Hasek, reflection and laughter.

Anyway, in his novels there are several Pragues. One is the cheerful city through which beautiful women and men walk who often have a point of ridicule, with their insurmountable desire to conquer girls. Another very different Prague is the one in which the writer lived after the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops in 1968. That Prague of the neo-Stalinist regime was an uncivilized city, in which, in its streets, both men and women walked hysterical, angry and were not characterized by their courtesy.

The conflicting opinions of Vera and Milan Kundera for me represent humanity divided into two parts that never agree: the one that accepts exile as an opportunity to grow and the one that paralyzes its life in the longing for the lost.

During the fifties and sixties, Kundera argued, emigrants from communist countries were not much loved in Western Europe, where fascism, then, was regarded as the real evil: Hitler, Mussolini, Franco's Spain, the dictatorships of Latin America. Only in the late sixties and seventies did Western countries decide to consider communism as a lesser evil. It was from The Unbearable Lightness of Being that many readers began to understand what communism was in Central Europe; before reading Kundera, some left-wing Western intellectuals still flirted with Soviet communism without openly condemning it.

Books by Milan Kundera in a Prague bookshop on Wednesday. DAVID W CERNY (REUTERS)

Along with exile and the growing impossibility of any rootedness, Kundera pointed out ignorance as another of the essential conditions of contemporary being: the ignorance of what suits us and, therefore, of what we are. In his novel entitled precisely Ignorance he continues his personal reflection around a question that he already formulated years ago and that returns in his books again and again: "Does man, in a world, have any chance, in a world where external determinations have become so overwhelming, that the inner motives no longer count for anything?"

Kundera, in addition to his novels, published important essays. The kidnapped West, published in 1983, when he had been exiled in France for six years, is one of them and of absolute validity. Geographical Europe has always been divided into two halves that have evolved separately: one, linked to ancient Rome with the Latin alphabet as a sign of identity, is anchored in the Catholic Church and Protestantism; the other is linked to Byzantium, the Orthodox Church and the Cyrillic alphabet. In 1945, the author claimed, the border between the two Europes shifted several hundred kilometres to the west. In this way, the inhabitants who always believed themselves to be Westerners, one day woke up to find that they were from the East. These surprised inhabitants are those who inhabited the cultural territory that the Czech-French writer calls Central Europe.

According to Kundera, the Austro-Hungarian Empire represented a great opportunity to create a strong state in the center of Europe; however, Kundera claimed, Austrians were torn between following "the arrogant nationalism of greater Germany" and their own Central European mission; that is why they failed to build a federal state of equal nations. "Its failure was that of the whole of Europe," because dissatisfied, the many nations of the region blew up the Empire in 1918. Thus the Empire was divided into an area with many small countries whose fragility allowed first Hitler and then Stalin to subjugate them. "Have all the efforts we have made to resurrect our people been worth it?" However, the writer concluded that the contribution of Czech culture between the wars was extraordinary.

This essay, like his novels, so influential in the years of their first publication, today, in the midst of the Russian war against Ukraine, acquire a particular meaning, in addition to taking on a new topicality. Kundera speaks of Russia's imperial dreams, of the desire to seize as many peoples as possible and affirms that in the nations that "have not yet perished", as the Polish anthem says, the vulnerability of Europe becomes visible: of all Europe. In Kundera's contemporary world while writing his essay, but also in today's world, "all European nations run the risk of soon becoming small nations and suffering their fate. In this sense, the destiny of Central Europe appears as the anticipation of the European destiny in general, and its culture immediately acquires great topicality."

Kundera based his opinion not only on modern history and politics; but also in Central European literature: in Hermann Broch's The Sleepwalkers, where history appears as a process of degradation of values; in The Man Without Attributes, by Robert Musil, which describes a euphoric society, which does not know that tomorrow it will disappear; in The Adventures of the Good Soldier Švejk, by Jaroslav Hašek, where the simulation of idiocy is the last chance to preserve freedom; and in Kafka's fictional visions that speak to us "of the world without memory, of the world after historical time". All the great Central European creation, since the beginning of the twentieth century, could be understood following Kundera as a long meditation on the possible end of European humanity. Let's keep reading it, then, because it keeps talking about the essentials.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Read more

I'm already a subscriber