In one of the beautiful stories in the "Extracts" file, which has just been translated into Hebrew by Persimmon, Anna Maria Yukel writes about a visit to the Stalactite Cave near Beit Shemesh. In the cave stands the narrator facing what appears to be a fairly ordinary pillar, a sentry and a stalactite that have come together, one growing from the floor and the other from the ceiling. Only a closer look reveals that a tiny space still separates them. To the unprofessional eye it seems as if the space is about to be filled in a short time - that is, short in terms of stalactite cave - but the experts explain that the space will no longer be filled. The sentry and the stalactite will never meet: prevention in principle does not allow them to meet.

Yukel lingers for a moment on this ongoing and thorough prevention. It describes how visitors to the cave faced the "abstract sculpture of 'eternal prevention'", and suddenly realized that the same fate befell rocks, stars and humans, that "everyone has the same tragedies of prevention, because of nature's whim, because of chemical coding retroactively, because of God or "A jealous man or just a blind case, understood Tantalus and Orpheus and Eurydice, Iago and the Dead Moon, Schubert, who never had a piano, and her and him and you and me."

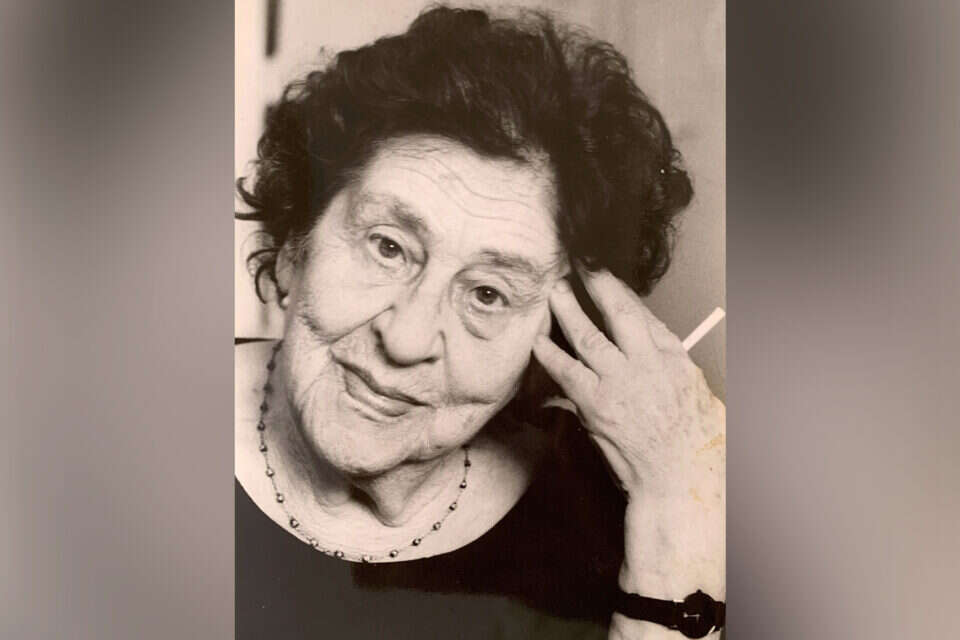

The principled, tragic but at the same time dry-factual prevention, which is repeated in many different forms from the short stories in the file, describes not only many of Yukel's characters, but also her own life. Although she began writing at a young age, she published two esteemed children's books and dealt with plays and the press, later Yokel did little to write. For most of her life she traveled between European cities, until she immigrated to Israel in 1965 and lived in Jerusalem until her death at the age of 90, in 2001. Although the stories collected in "extracts" were probably written throughout her life, they were published in Germany only in the last decade before her death. In Israel only now, two decades after her death.

Yukel's life was full of wanderings. She was born into a Viennese Jewish family in 1911. Her father, who served as a soldier in World War I, returned sick and died when she was 13, and the family moved to Berlin, which in those pre-war years was a vibrant cultural city. Yukel experimented with experimental theater and cinema, and later moved to Prague, where she lived until 1939, but with the Nazi invasion fled to London and spent the war years there.

After the war ended, Yukel decided to specialize in psychology - even though she did not have a high school diploma and did not attend university - and began training in Zurich with Carl Gustav Young, one of the fathers of psychoanalysis, but did not complete her training. She returned to Berlin, where she engaged in psychotherapy (outside the psychoanalytic establishment, in the absence of official certification), and after she was also forced to leave Berlin, she immigrated to Israel.

In Israel she worked as a psychotherapist, living alone, without a spouse or children, but was surrounded by friends and maintained deep and long-standing friendships.

Her close friend Ita Shedletsky, Professor Emeritus of German Literature at the Hebrew University, tells of the meeting between Yukel and Martin Buber as one of the highlights of her later life, and as an expression of deep emotional closeness.

In Yukel's library, Sheldecki found Buber's autobiographical book, "Meeting," which he apparently gave her at their last meeting in late 1964. On the book he wrote a dedication to her with the greeting "Meet Again."

However, when Yukel immigrated to Israel in 1965, it was about a month after Buber's death in Jerusalem.

The six living beings

The miniature stories in "Extracts" jump between the stations of Yukel's life, without telling almost anything about her biography. We know the narrator is once in this city and once in another city, but we do not know what brings her to move from place to place. The narrator's character and the crises that befall her are mostly revealed through her ways of looking at characters that have attracted her heart, about animals and about external and internal landscapes.

"The life story of Anna Maria Yukel may be unusual," says Hanan Elstein, the book's translator from Germany, "but it is not much different from that of people in Europe of her time. And with the description of that part of life that is left behind, because of the language. "

These departures and disconnections, for Yukel, are first and foremost a disconnect from the language.

In this respect, she writes, leaving Berlin was especially painful for her, because in her wake she had to disengage not only from the German language, which she knew about, but also from the creative experiences in cinema and plays, which were indeed not renewed.

And yet, Yukel writes, her years of wandering - between Vienna, Berlin, Prague, London, again Berlin, and Jerusalem - nevertheless paint, precisely in their upheavals, an encrypted picture of the period in which she lived.

She writes in a short autobiographical passage in the book: "In a geographical drawing these were six living beings, always in relevant foci of our age ... If every stage is a glass panel, with its unique mark engraved on it, they are all laid on top of each other "It may be revealed to the hieroglyphic eye of the age."

"She paints a sober and very non-didactic view of historical reality," Elstein says.

"In her voice, in her sheer delicacy, there is something that will speak to anyone who wanders or is exiled, voluntarily or coercively. She recreates contacts, wanderings, between places and people, almost all of whom are portrayed as ghosts of the past. There is no crying there, which is typical of many writers today. She went through a lot of things and turned it into a source of power. For 17 or 18 years, I have been tossing my feet among the book publishers in Israel in an attempt to interest them in the book, and they all refused. "

Mental closeness.

Buber,

Thoughts on the big bang

Yukel's friends from Jerusalem, including, along with Sheldecki, the couple Yonatan Cohen and Michal Padua, talk about the breadth of her education and her surprising interests, which also included physics, sumo wrestling and reality series about judges. And yet, they say, she shyed away from local politics, even though in her later years she lived at 5 Balfour Street in Jerusalem, next door to the prime minister's residence. "She came to Israel out of her connection with Martin Buber and Gershom Shalom, and out of the perception of existence here as part of the liberation of the Jewish people, but over time she was probably disappointed by the degree of humanism left in Zionism," says Cohen.

"What made it harder for her in her first years in the country," says Shdelatsky, "was the fact that since about 1970 she has not actually been involved in writing at all. She has experienced this as a kind of unbearable silence." Only towards the end of her life did she return to write and publish her early works in Germany.

Sheldecki says that "in the last years of her life, Yukel concentrated more and more on physics, mathematics and the universe in general. She followed new research with curiosity, devoting thoughts to the Big Bang phenomenon." Her first novel for children, "The Real Miracles of Basilius Knox," which tells children about the laws of physics, was reissued in Germany in the late 1990s.

Another of her books, which was republished in Germany, is an analysis of two treatment cases that came to her clinic in Berlin after the Holocaust: one - a Jewish man, the son of Holocaust survivors, and the other - a German man, the son of the Nazis. She took care of both of them at the same time before immigrating to Israel. Her analysis, which finds launching points between the children of the murderers and the children of the victims, was very innovative for its time, and for many years preceded the prevailing perception today among psychologists that the Holocaust caused damage to the descendants of both sides.

In addition, an autobiographical book written by Yukel entitled "The Journey to London" was published in Germany, as well as a selection of texts from her estate entitled "On the Six Lives" (Aus six Leben) which was published in 2010. In 1995 she was awarded a prize in Germany for The name of the German writer Hans Erich Nossack for the entirety of her work, and according to Sheldecki she is very happy to fly to Germany for the last time in her life, to receive the award.

Training in Zurich.

Young,

Kafka's anonymous sister

Compared to Germany, in Israel Yukel is almost completely anonymous, even among lovers of German literature. The only book Perry Atta published before "Extracts" is "The Color of the Pearl," a novel for teenagers translated by Nitza Ben-Ari in 1992, published by Am Oved, which describes a conflict between two school classes that takes on fascist nuances. "The book was included in Germany in lists of classics for teenagers from the 20th century, and critics said that if it had not been for its misfortune, it would have become a familiar classic like Emil and the detectives," says Elstein. He adds that "she was a very sociable person who loved people, but lived in literary solitude and no one from the literary establishment in the country knew her. In Germany, however, in her death, obituaries were written about her in the most important newspapers."

Having special translation difficulties?

"Yukel's summary, because of the compactness, has an almost poetic effect. And Hebrew is not an easy language for the delicacy of her writing. It's like subtle humor does not work in Hebrew. She wrote in German - but she wrote in Israel, and the language was a lost homeland for me. The delicacy, density, accuracy, and sense that the characters, even if they are not 'round' in their description, are full of the experience they evoke in us.

"And there was something else," Elstein adds, "it's a collection of stories, impressions, memoirs - you could perhaps define them as 'diaries' - written over time, in different life situations and in different places. Usually, shortly after the translation work begins, the translator captures the "The language of the writer, but here each story was completely different. I felt like I was translating an anthology of different writers. Although there are similarities between the stories, I felt that in each story I had to pay the 'entry price' for the story, as if it were a whole new writer."

In one of the stories in the book, "A Stone on an Unknown Tomb," Yukel writes about Kafka's anonymous sister, Otella, who was her friend when she lived in Prague. She describes Otella as a Kafkaesque character, collapsing under her family duties, to the tragic end, which is also, to some extent, as in her brother's stories, the fulfillment and overwhelming redemption of her character -Yokel writes.

The story of Otella was translated into Hebrew by Ephraim Broida and published in the journal Moled in the late 1960s, and according to Elstein, this fact added a special difficulty to the translation work. "After Yokel read Broida's translation," says Elstein, "she said that is how she would like to sound in Hebrew. If she were alive, she would approve of him. "

Elstein testifies that most of all, he loves the delicacy and elusiveness in Yukel's writing.

"The ability to tell about characters animates them for a moment, but only as fluttering, partial beings. And yet, her writing allows us to feel great empathy for these characters - whether she writes about turtles or people. We hardly know what these characters look like, we have almost none "Realia data on them, there are no exposures, they are almost abstract figures. But she is in the position of an attentive observer who seeks the sheer humanity of her figures, and gives us, in her human encounters, small points of light."

From the book:

Old Jan |

Anna Maria Yukel

He remains alive in memory more than many other people I have known in London over the years. I just have to close my eyes and think of old Jan, and he comes and approaches seemingly, leaning slightly on his stick, but still big and firm, and on the carved face his mischievous Slavic smile. He was old when I met him, and he died soon after. And yet, despite the brief acquaintance, the encounter with old Jan was one of the most significant encounters that had been inconceivably piled up in the last few months of my stay there, as if desolate London were suddenly destined to be filled with meaning.

As for old Ian: I have witnessed the fate of a man in his final history, in recent days - as it turned out - his colorful life, dark of redemption, a witness also to their unexpected solution.

We usually meet people in a sequence of yesterday-today-tomorrow, with life flowing like endlessly. But old Jan, with the split given at the heart of his existence, clearly came close to the great entrance gate. His innocent tragedy was that of a Greek myth, for he was captivated by the spell of the magic of mighty, kind of hidden ghost shadows. And since the thing he pursued was inconceivable, he - ostensibly a chosen destiny, a success story in music and literature and among women - always remained in a waiting position, devoured by expectation, pushed back to the blows of fate. For like a ray of light gliding fast through space and inaccessible from the moment it is sent, so did its ghosts feel before it.

Born in the last quarter of the last century, he grew up named Hans, the son of a small civil servant in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, studied and became a librarian in Hofburg, the imperial palace in Vienna. And yet - as he recounted the last evening before he left for Warsaw - he never had the feeling that his simple, limited parents were not his real parents, without any signs to the contrary.

It seems that man simply has to know what his origin is; And it seems that something in the depths of man feels when its source is not real, and then a sublime uneasiness from understanding takes him away from the ordinary paths of life. The Oedipus complex is just one version of this theme.

Hans, Hofburg's librarian in Vienna, searched and researched for years, until he finally came across a secret case in which it was said that he was the illegitimate child of a Polish countess and her portrait painter, and that immediately after birth he was given a heavy coat of secrecy for adoption.

It took a long time and great effort to locate the mother's fuzzy traces - she is already divorced from the Count and remarried in America. He went to America, met the woman who was still charming; But about her passionate Polish lover she knew nothing but the name.

From that day onwards Hans sought it, for years, decades - in vain. He adopted his father's name, called himself Jan and began learning Polish. He learned the language so well that forty years later, when I met him, the former "Imperial and Royal" librarian in Hofburg - Austrian and Hungarian - spoke German with a Polish accent. At the end of World War I Jan made his way to Paris, where Pilsudski prepared his army for a return to independent Poland again. Jan became his third, and when Pilsudski's third came to his unfamiliar homeland.

In this way he tried, persistently unheard of as its example, to untangle the tangle of his existence; And Poland fascinated him, the believing Catholic in spite of his great sophistication, with the colorful life in the metropolitan areas of Europe, with an insatiable longing.

Then came the conquest of Poland, World War II, and Jan landed in London and was employed by the Polish government in exile on cultural missions.

He told the story of his life, about the turmoil of his life, on the eve of his planned trip on a cultural mission to Poland that had become communist.

Gomolka or Pilsudski, it was not essential to Ian.

It was Poland, Poland!

He traveled for two weeks.

He did not return.

He died in Warsaw after two weeks, in a Catholic hospital, alone, but twice as many at home.

And perhaps, in his last twilight, the miraculous shadows forever turned around and finally gathered him into their arms.

From German: Hanan Elstein; From "Extracts" (Persimmon, 2021)